Joshua 10 and 11: Genre, repetition, and redundancy

In the previous post we saw how the language of annihilation in Joshua 10 and 11, far from being something unexpected, was actually a common feature across ancient Near Eastern conquest accounts. This time we’re going to look at another feature we noticed a couple of posts ago: the text’s repetition and redundancy in the way it records the Israelite conquest of Canaan. We’ll see how it too is a common feature in ancient conquest accounts.

We find repetition throughout these two chapters, but to illustrate the point let’s look at Jos 10:29-38:

Jos 10:29 Then Joshua passed on from Makkedah, and all Israel with him, to Libnah, and fought against Libnah. 30 The LORD gave it also and its king into the hand of Israel; and he struck it with the edge of the sword, and every person in it; he left no one remaining in it; and he did to its king as he had done to the king of Jericho.

31 Next Joshua passed on from Libnah, and all Israel with him, to Lachish, and laid siege to it, and assaulted it. The LORD gave Lachish into the hand of Israel, and he took it on the second day, and struck it with the edge of the sword, and every person in it, as he had done to Libnah.

33 Then King Horam of Gezer came up to help Lachish; and Joshua struck him and his people, leaving him no survivors.

34 From Lachish Joshua passed on with all Israel to Eglon [LXX: Adullam]; and they laid siege to it, and assaulted it; and they took it that day, and struck it with the edge of the sword; and every person in it he utterly destroyed that day, as he had done to Lachish.

36 Then Joshua went up with all Israel from Eglon to Hebron; they assaulted it, and took it, and struck it with the edge of the sword, and its king and its towns, and every person in it; he left no one remaining, just as he had done to Eglon, and utterly destroyed it with every person in it.

38 Then Joshua, with all Israel, turned back to Debir and assaulted it, and he took it with its king and all its towns; they struck them with the edge of the sword, and utterly destroyed every person in it; he left no one remaining; just as he had done to Hebron, and, as he had done to Libnah and its king, so he did to Debir and its king.1

As we mentioned a couple of posts ago, this isn’t prose. This isn’t history writing. The language is too stylized. It’s too formulaic.

The formula is pretty clear and looks like this:

Joshua went (? from A) with All Israel to B, (? laid seige to it) and assaulted it and took it (? that day), and struck it with the edge of the sword (? it’s king) (? and its towns) and utterly destroyed every person in it (? he left no one remaining), just as he’d done to A.

There are variations of course. Some phrases always appear (“struck it with the edge of the sword”), others appear most of the time (“utterly destroyed”), and others more rarely (“and its king and its towns”). The order of the phrases vary a little too. But the general formula is undeniable – the same words and phrases are repeated over and over in a very similar order.

The whole section could be made much shorter by removing the redundant phrases. Nothing would be lost; the same information would still be conveyed. So why does the repetition and redundancy remain?

It should be no surprise by now, but describing events in such formulaic ways is typical of the Ancient Conquest Account genre.

Repetition and redundancy in comparative literature

About the Joshua passage we’re looking at Hess writes,

Such an annalistic style is well known in the recording of Hittite and Assyrian campaigns, where the overall pattern is repeated but specifics are altered according to the unique elements involved in capturing each town.2

Let’s take a look at a few examples.

Assyrian annals

On his “marble slab inscription” Shalmaneser III – the same Shalmaneser that Jehu son of Omri3 is depicted as paying tribute to on the Black Obelisk – recorded, amongst other things, his dealings with the Hittites. Here’s what he recorded of his activities in his 17th year on the throne:

I crossed the Euphrates. I received the tribute of the kings of the land of Hatti. I went up to Mt. Hamanu. I cut down logs of cedar and juniper. I brought (them) to my city Aššur. On my return from the Mt. Hamanu: I killed 63 mighty wild bulls, with horns, perfect specimens in the area of the town of Zuqarri on the opposite bank of the Euphrates River. I caught 4 alive with (my) hands!4

And in his 19th year:

I crossed the Euphrates River for the 17th time. I received the tribute of the kings of the land of Hatti. I went up to Mt. Hamanu. I cut down logs of cedar and juniper. I brought (them) to my city Aššur. On my return from the Mt. Hamanu: I killed 10 mighty wild bulls, with horns, perfect specimens (and) 2 calves (as hunted game) in the area of the town of Zuqarri on the opposite bank of the Euphrates River.5

It hardly needs to be said that this is highly stylized and formulaic language. Two different excursions described in exactly the same way, in exactly the same language. This isn’t what we expect to see in history writing, but it’s how the Assyrians recorded their conquests.

Though we could look at many other examples, this one was chosen because it illustrates the point well – it is extremely repetitive and formulaic.

We could look at any of the annalistic texts of Tiglath-Pileser I, Ashur Dan II, Assur-nasirpal II, and Sennacherib and find similar highly repetitive, and redundant records of their conquests across the ancient Near East.

But, this is a blog post, not a PhD thesis, so let’s leave the Assyrians behind and move on to the Hittites.

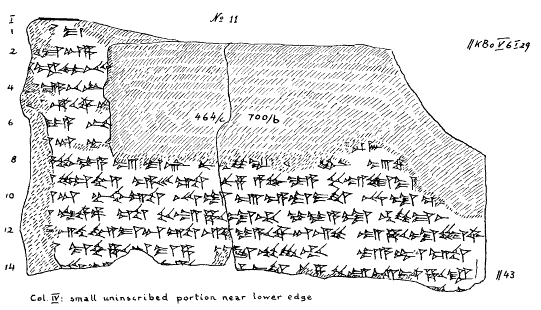

Hittite annals

In the late 1300’s BCE a Hittite king by name of Mursili II wrote up the “Deeds of Suppiluliuma”6; his fantastically named father.

Fragment 14:

[Thus (spoke) my father] to my grandfather: [“Oh my lord!] Against the Arza]waean [enemy send] me!” [So my grandfather sent my father] against the Arzawaean enemy. [And when] my father [had marched for (?)] the first [day?, [he came? to the town of? ]-ašha. [The gods] ran before [my father:] [the sun goddess of Arinna, the storm god of Hatti, the storm god of the Army, and Ištar of the Battlefield, [(so that) my father slew the] Arzawaean [enemy]. and the enemy troops [died in] multi[tudes …

Fragment 15:

they brought word to my father below the town of [.…]: “The enemy who had gone forth to (the town of) Aniša, is now below (the town of) […]-išša.” (So) my father went against him. And the gods ran before my father: the Sun Goddess of Arinna, the Storm god of Hatti, the Storm god of the Army, and the Lady of the Battlefield. (Thus) he slew the aforementioned whole tribe, and the enemy troops died in multitudes.

Fragment 50:

Then he marched forth on that very day [.…] But the enemy came in multitudes. But when it became light and the sun rose, he went.… to battle [and] he fought […] And the gods [ran before] my father: [The sungoddess of Ari]nna, the stormgod of Hatti, the stormgod of the Army, [the god X, the god Y], Ištar of the Battlefield and Zababa, [(so that) the enemy troops] died in [multi]tudes.

Again we find the same thing: three different conquest accounts written in a formulaic, repetitive style. That’s how the Hittites recorded their conquests.

Conclusion

When we come back to Joshua 10:29-39 we find writing in the same style. The passage is written following the same rules as the conquest accounts of Israel’s neighbours, by following formula, tweaking for details like place names, but otherwise being very repetitive.

What does that mean? Well, it’s nothing sinister. It’s just evidence that the Israelite culture overlapped with those of her neighbours. Her conquest accounts were written in the same way as those of the Assyrians and Hittites. As such, we shouldn’t assume that we can take them at face value. We need to understand the genre before we can work out what the writers meant, and certainly before we go digging for archaeological evidence to support face-value readings of the text.

In our next post we’ll take a look at the third common feature we found in Joshua 10 and 11: hyperbole. That should get the fundamentalists hot under the collar :)

Further reading

- William W. Hallo and K. Lawson Younger, Context of Scripture (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2003), xxi–xxvii.

- K. Lawson Younger Jr., Ancient Conquest Accounts: A Study in Ancient Near Eastern and Biblical History Writing (vol. 98; Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1990)

Featured image

A photo I took in Karnak Temple, Luxor, shortly after being teargassed.

Footnotes

-

All scripture quotations unless otherwise noted are from the New Revised Standard Version (Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1989) ↩

-

Richard S. Hess, Joshua: An Introduction and Commentary (vol. 6; Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries; Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1996), 223–224. ↩

-

Jehu was not the son of Omri, yet he’s described that way on the Black Obelisk. This is helpful background for biblical genealogies – a topic for another time. ↩

-

K. Lawson Younger Jr., Ancient Conquest Accounts: A Study in Ancient Near Eastern and Biblical History Writing (vol. 98; Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1990), 100. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Hans Gustav Güterbock, “The Deeds of Suppiluliuma as Told by His Son, Mursili II,” Journal of Cuneiform Studies 10, no. 2 (1956): pp. 41-68. ↩