Israelite Origins: Population decline and explosion

In the preceding posts in this series we’ve seen how the scriptures do not speak in one voice when it comes to figuring out exactly where the Israelites came from.

- Instead of there being a single “biblical” date for the conquest we’ve seen that several can be derived from the text.

- Instead of the Israelites running the show in Canaan as we’d expect from the first half of the book of Joshua, we’ve seen that Egypt, for 250-300 years starting from around 1450 BCE, completely dominated the area (and that precisely nothing is said about this in the books of Joshua or Judges).

- And, instead of finding archaeological evidence of sweeping destruction throughout Canaan at a time that lines up with either the Early or Late Date Exodus and Conquest, we find little evidence of systematic destruction, or of cultural change. In some cases we even find that cities said to have been defeated by Joshua didn’t even exist at the time.

It’s felt like a whole load of deconstruction – the rosy picture painted in Sunday School has all but shattered.

From now on in the series we’re going to see what can be salvaged. What can we know about Israelite origins? In this post we’re going to look at the data for the archaeological phenomenon known as the “Israelite Settlement”, but but we’re going to start one stage before that – the Late Bronze Age population decline.

Population Decline

As we already touched upon in a previous post, one policy that the Egyptians put in place during their domination of Canaan was its depopulation. Redford explains:

Thutmose III carried off in excess of 7,300, while his son Amenophis III uprooted by his own account 89,600. Thutmose IV implies that he carried off the inhabitants of Canaanite Gezer to Thebes, while his son Amenophis III speaks of his Theban mortuary temple as “filled with male and female slaves, children of the chiefs of all the foreign lands of the captivity of His majesty – their number is unknown – surrounded by the settlements of Syria.”1

This “deportation of a sizeable segment of the population” was to leave “the highlands sparsely occupied”.2 The decline in population wasn’t limited to one segment of society, or to one or two areas of Canaan. Rather, as Mazar explains,

The fringe areas were deserted, and some of the sites which had been important urban centers in MB II were either fully or partially abandoned… There was also a decline in the rural settlement, particularly in the hill country. The archaeological surveys in Samaria and Ephraim have shown that the many small Middle Bronze Age agricultural settlements in these regions disappeared in the Late Bronze Age.3

Some areas became entirely empty. Indeed, as Mazar states emphatically,

The Late Bronze Age in the Judaean Highland is a void.4

Rivka Gonen has written extensively on the subject and outlines the change in pattern as follows:

Intensive archaeological surveys in various parts of the country round out the observed pattern of a significant decline in the number of sites. Whereas 270 Middle Bronze sites were counted, only 100 Late Bronze sites were found, a decrease of more than 60 percent.5

So, the number of towns and villages people lived in declined between the Middle Bronze (2000 – 1550 BCE) and the Late Bronze age (1550 – 1200 BCE). Gonen does point out that though there had been “near abandonment of the hill country”, there had been an increase in the population of the low-lying areas, “though the sites were generally small”.6

At the end of a fascinating paper in BASOR entitled “Urban Canaan in the Late Bronze Period”, Gonen summarised the data for the changing population size between the Middle and Late Bronze ages like so:

This, no doubt, indicates both a substantially smaller population [in the Late Bronze] than in the Middle Bronze period, and a breakdown of the system of medium to large city-states that formed the backbone of Middle Bronze Age Canaan.7

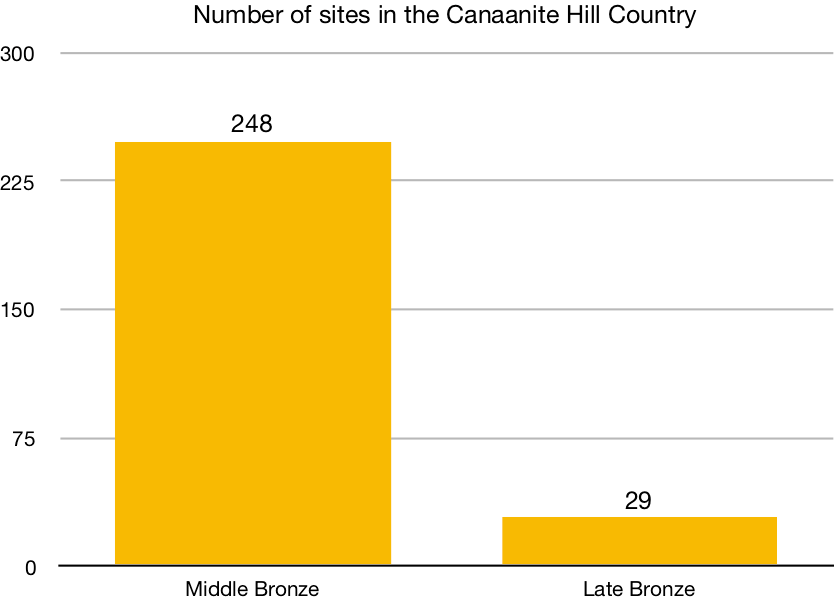

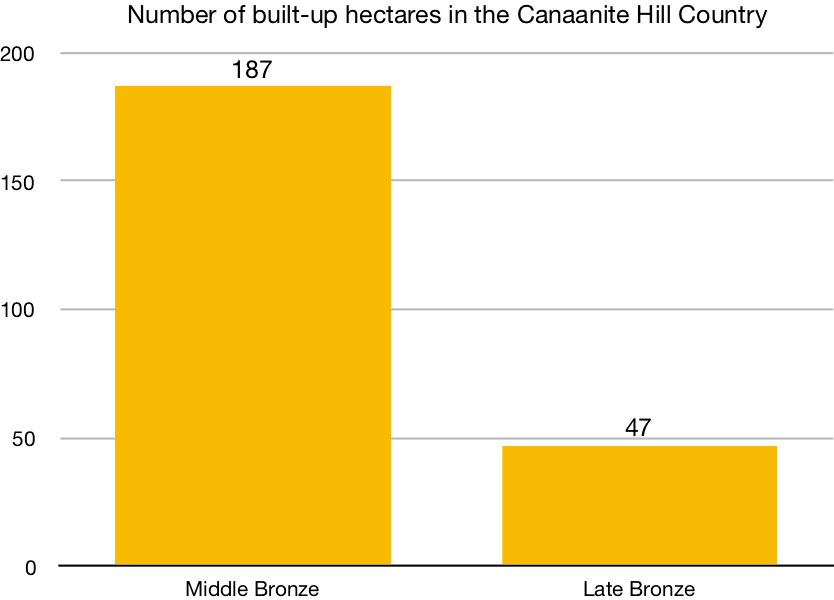

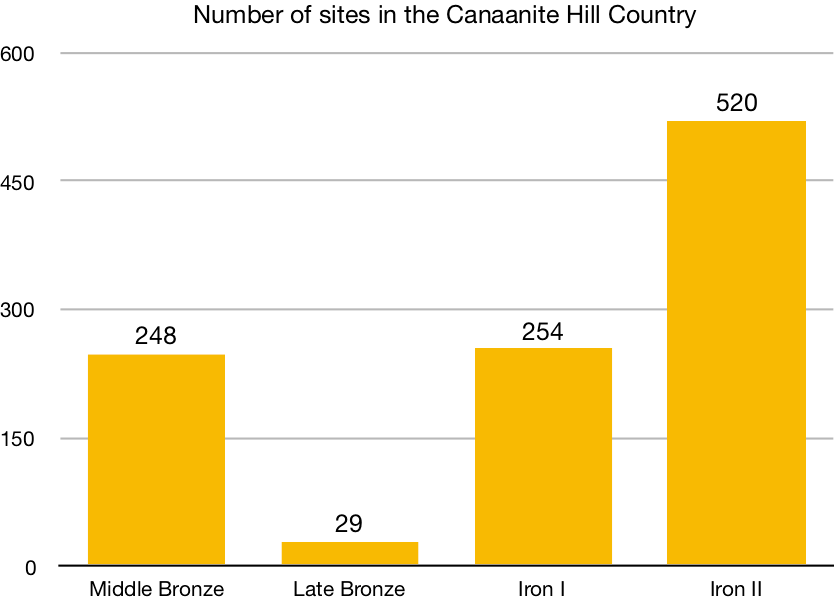

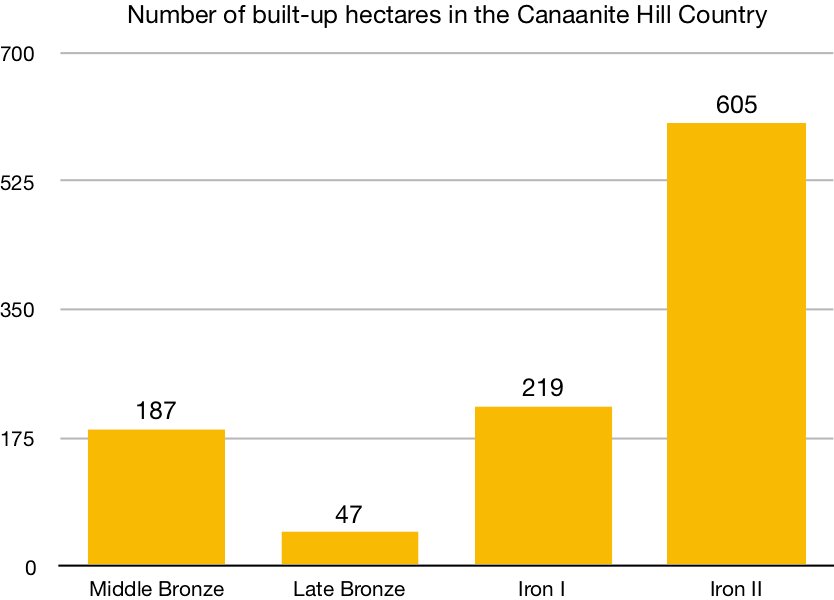

Finkelstein and Na’aman, in their excellent “From Nomadism to Monarchy” provide some summary data that help illustrate the point.8 Here are two graphs that focus on the hill country. The first shows how many sites there were in the hill country in the Middle and Late Bronze ages; the second shows the number of built-up hectares across the two periods in the same area.

It’s pretty clear that compared to the Middle Bronze age, the Late Bronze age Canaanite hill country really was practically empty.

Population explosion

Starting around about the beginning of the Iron Age (~1200 BCE), everything changed. Where the Late Bronze Age Canaanite Highlands saw population decline, the beginning of the Iron Age I saw a population explosion. Where for a long time there had been only crickets, hundreds of new sites appeared – a phenomenon known as the “Israelite Settlement”. Mazar begins his section on the topic like this:

Intensive archaeological surface surveys revealed an entirely new settlement pattern in Iron Age I. Hundreds of new small sites were inhabited in the mountainous areas of the Upper and Lower Galilee, in the hills of Samaria and Ephraim, in Benjamin, in the northern Negev, and in parts of central and northern Transjordan. Much of this activity can be related to Israelite tribes, though the ethnic attribution in some of these regions is still questionable.9

He then fills the next few pages with summary information about what was found in the areas listed above – it’s definitely worth a read.

The surveys Mazar refers to (“The Archaeological Survey of Israel”) were performed over a period of a few decades starting in the 1950s and involved teams of archaeologists walking every square mile of the entire country recording everything they found. During the course of these surveys many sites from the Iron 1 period were discovered bringing the Israelite Settlement to light – the archaeological evidence of the appearance and settling down of the Israelite people.

Finkelstein writes about this survey and its results in his well known book, The Bible Unearthed,

These surveys revolutionized the study of early Israel. The discovery of the remains of a dense network of highland villages – all apparently established within the span of a few generations – indicated that a dramatic social transformation had taken place in the central hill country of Canaan around 1200 BCE… In the formerly sparsely populated highlands from the Judean hills in the south to the hills of Samaria in the north, far from the Canaanite cities that were in the process of collapse and disintegration, about two-hundred fifty hilltop communities suddenly sprang up. Here were the first Israelites.10

Finkelstein makes the important point that these Iron 1 sites were almost all new villages not built on the site of older ones. We can find reference to this point in excavation reports, for example Calloway’s summary of the Iron I discoveries found in the excavations at Et-Tell (“Ai”):

The Iron Age I settlement at Ai was one of many established in the region about the same time by people who moved in and occupied abandoned sites of cities, such as Tell en-Nasbeh and el-Jib (Gibeon), or new sites such as Mukhmas (Michmas), Rammun (Rimmon), Taiyiba (Ophrah?), Raddana (Ataroth?), el-Ful (Gibeah), and many small campsites on hilltops in the area. Bethel was the only city occupied in the Late Bronze Age, and it was destroyed at the beginning of this period, so the blame may be laid upon the newcomers. Iron Age I housing and artifacts at Bethel share the general characteristics of houses and finds at the newly established sites… We may view the settlement at Ai, therefore, as part of a considerable influx of newcomers who infiltrated the area and apparently met little or no resistance.11

Dever expands on the point that these were new sites, writing,

The new Israelite settlements… are almost all founded de novo, not on the ruins of destroyed Late Bronze Age sites, but in the sparsely populated hill country extending from Upper and Lower Galilee, into the hills of Samaria and Judah, and southward into the northern Negev.12

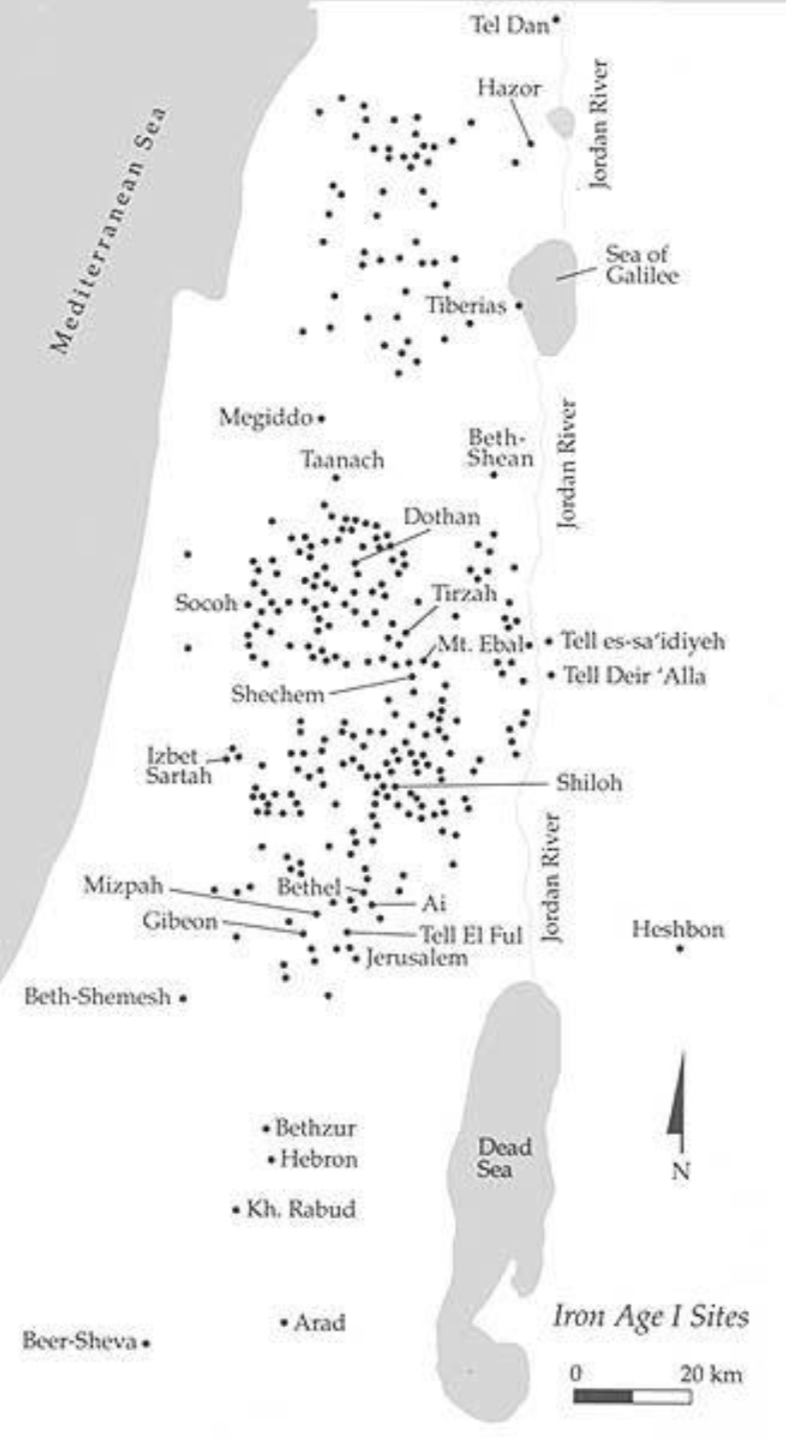

So, where are these Iron I sites? This map from The Rise of Ancient Israel shows their distribution across Canaan:

All that’s required is a passing knowledge of Israel’s topography to see that the vast majority of the sites are in the hill country: far from the main north-south road running along the coast, far from the centres of population, and far from the best agriculturally productive land.

Let’s get into a bit more detail and look at the numbers. Expanding on our previous use of Finkelstein’s data, here are some graphs that illustrate the population decline (as we saw above) and explosion in Iron I (followed by Iron II).13

Both graphs demonstrate quite clearly the massive increase in the number of sites from the Late Bronze age to Iron I.

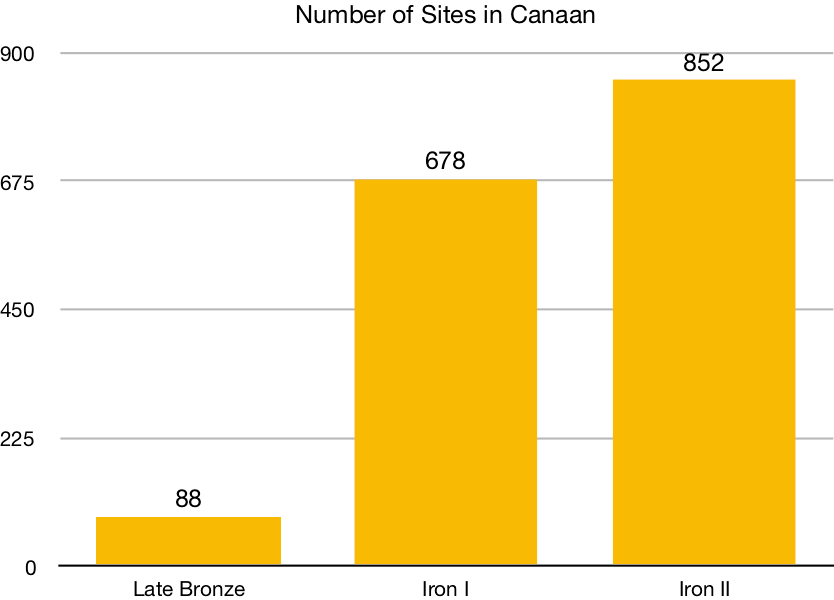

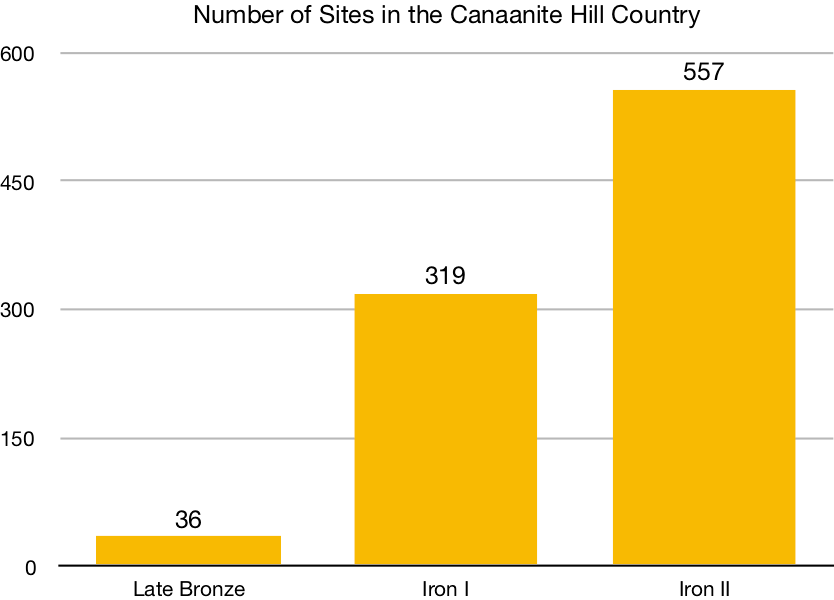

A slightly more sophisticated14 and up-to-date set of numbers can be found in Lawrence E. Stager’s chapter “Forging an Identity” in The Oxford History of the Biblical World. In it we find figures not just for the Canaanite hill country but for all of Cis-Jordan and Transjordan (the lands west and east of the Jordan river respectively). For both that larger area and the highlands-specific area here’s the summary data15:

| Late Bronze | Iron I | Iron II | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Canaan | 88 | 67816 | 852 |

| Canaanite hill country | 36 | 319 | 557 |

Here are a couple of graphs based on Stager’s more up-to-date data:

You’ll notice that between Stager and Finkelstein the figures are different – that doesn’t matter. Though Finkelstein’s data is older, it shows the same pattern as the latest data. And that pattern is clear – a massive increase in the number of sites in the Canaanite highlands.17

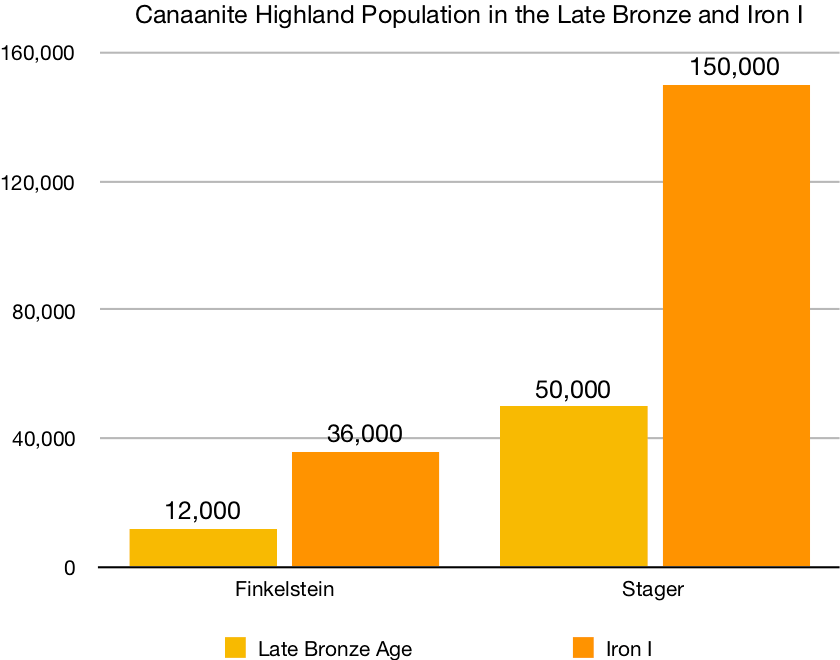

Both Finkelstein and Stager translate the number of sites and their area into population figures. Here’s the data:

| Late Bronze Age population | Iron I population | |

|---|---|---|

| Finkelstein | 12,000 | 30,000 – 42,000 |

| Stager | 50,000 | 150,000 |

Here’s a graph based on them:18

Again, regardless of the fact that Stager’s more up-to-date figures are different to Finkelstein’s, the pattern is what matters: the population in the Canaanite highlands in Iron I is three times what it was in the Late Bronze age. That’s a huge increase in population.

So, these new sites… who lived in them?

Let’s repeat a few quotes we’ve already seen, and add a couple of new ones:

The continuity between many of these sites and later Israelite towns and villages of the monarchic era legitimizes the definition of these settlers as Israelites, as I have maintained since I excavated the site of Giloh in 1978, and as have many other scholars. The term “Proto-Israelites” introduced by Dever and adopted by others to designate the inhabitants of these sites is in my view superfluous.19 – Amihai Mazar

Here were the first Israelites.20 – Israel Finkelstein & Neil Silberman

The new Israelite settlements, by contrast, are almost all founded de novo…21 – William G. Dever

That many of these villages belonged to premonarchic Israel is beyond doubt.22 – Lawrence E. Stager

I could go on all day. We can even find minimalists who agree, even if through gritted teeth:

This development from outlaw habiru to sedentary Israelite mountain peasants took place over a couple of centuries, and can be followed directly in the archeological record of conditions in the highlands. In the thirteenth-twelfth centuries BCE a number of village societies arose in both the Galilean mountains and in the central highland (as far as the territory east of Jordan is concerned we are as yet insufficiently informed), in regions which had not been previously inhabited, as far as we can tell.23 – Niels Peter Lemche

It’s rare that practically everyone is in agreement.

So, we can safely say that the archaeological record is clear: the Israelites emerged in the Canaanite highlands at the beginning of Iron I (~1200-1000 BCE) and settled down in small villages which they built from scratch.

So… what does this mean for us?

Implications

First, let’s look at the implications for those who hold to an Early Date Exodus, i.e. one that began in 1446 BCE and ended 40 years later with the beginning of the Conquest in 1406 BCE. If this is your view, you’ve got a couple of problems:

- The period in which you’d expect to see a population explosion (the last couple hundred years of the Late Bronze age, i.e. ~1400-1200 BCE) caused by the influx of a few million Israelites instead saw a dramatic population decline. Why did the population decline if millions of Israelites had just turned up?

- The population explosion you’d expect to see starting a few years after 1406 BCE happened 200 years after you expected it to happen. How do you explain the population explosion that took place in the 12th and 11th centuries?

- Even if we take Stager’s figures over Finkelstein’s (not unreasonably, given they’re more recent), a settled population of 150,000 at the end of Iron I (~1000 BCE) is miniscule compared to the expected millions of Israelites normally assumed by those who hold to an Early Date Exodus. Why did the population only grow by thousands, not millions?

Next, the implications for those who hold to a Late Date Exodus:

- Though the timing of the population explosion is less of a problem for the Late Daters than it is for the Early Daters, it still presents something of an issue: though the settlement began around 1200 BCE, it didn’t really pick up much speed until after the Egyptians had left. And, there’s no evidence anyone was around in the hill country until the time of the Israelite Settlement. So, what were the millions of Israelites doing between the time they arrived in Canaan (approximately 1220 BCE according to the Late Date Exodus) and the time the Egyptian power was practically over (approx 1150 BCE)? Hovering above the ground, conveniently leaving no trace in the archaeological record?

- The same problem of population size that causes an Early Date Exodus problems also causes problems for the Late Daters. There’s archaeological evidence of Israelites in the 12thcentury, but only in the tens of thousands. Where are your millions of Israelites?

In conclusion, the archaeological record is pretty clear that the Israelites appeared in the Canaanite hill country early in Iron I (1200 – 1000 BCE) after the area had suffered a population collapse in the preceding Late Bronze age (1550 – 1200 BCE). In our next post we’ll start taking a look at the problem of where did the Israelites come from.

Further reading

- Israel Finkelstein, “The Emergence of Israel” eds., Israel Finkelstein & Nadav Na’aman, From Nomadism to Monarchy (Yad Izhak Ben Zvi, Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1994), 150-178.

- Rivka Gonen, “Urban Canaan in the Late Bronze Period,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (Winter), no. 253 (1984).

- Rivka Gonen, “The Late Bronze Age,” in The Archaeology of Ancient Israel (ed. Amnon Ben-Tor; New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1992), 211-257.

- Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible 10,000-586 B.C.E. (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 1990), 334-338.

- Lawrence E. Stager, “Forging An Identity,” in The Oxford History of the Biblical World (ed.Michael D. Coogan; Oxford University Press, 2001), 90-131.

- William G. Dever, Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2006), 91–100.

Footnotes

-

Donald B. Redford, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times (Princeton University Press, 1992), 208-209. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible 10,000-586 B.C.E. (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 1990), 239. ↩

-

Amihai Mazar, Studies in the Archaeology of the Iron Age in Israel and Jordan, vol. 331, Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series (Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001), 26. ↩

-

Rivka Gonen, “The Late Bronze Age,” in The Archaeology of Ancient Israel (ed. Amnon Ben-Tor; New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1992), 217. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Rivka Gonen, “Urban Canaan in the Late Bronze Period,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (Winter), no. 253 (1984): 69. ↩

-

The following graphs were created from the data found in Israel Finkelstein, “The Emergence of Israel” eds., Israel Finkelstein & Nadav Na’aman, From Nomadism to Monarchy (Yad Izhak Ben Zvi, Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1994), 154. ↩

-

Op. cit. Mazar (1990), 334. ↩

-

Israel Finkelstein & Neil Silberman, The Bible Unearthed (Touchstone, 2002), 107. ↩

-

Joseph Callaway, “Excavating Ai (Et-Tell): 1964-1972,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (Mar), no. 39 (1976): 29. ↩

-

William G. Dever, Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2006), 99. ↩

-

The following graphs were created from the data found in Israel Finkelstein, “The Emergence of Israel” eds., Israel Finkelstein & Nadav Na’aman, From Nomadism to Monarchy (Yad Izhak Ben Zvi, Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1994), 154. ↩

-

Op. cit. Dever (2006), 98. ↩

-

Lawrence E. Stager, “Forging An Identity,” in The Oxford History of the Biblical World (ed. Michael D. Coogan; Oxford University Press, 2001), 100. ↩

-

Quoted not once, but twice, by Dever as 687 instead of 678. See William G. Dever, Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2006), 98. ↩

-

There’s a tremendous increase in the number of new sites in Moab (170 of them!) but that’s a story for another time. ↩

-

These graphs are derived from Dever’s summary of Finkelstein’s and Stager’s data found in William G. Dever, Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2006), 98. ↩

-

Amihai Mazar, “Remarks on Biblical Traditions and Archaeological Evidence Concerning Early Israel,” in Symbiosis, Symbolism, and the Power of the Past: Canaan, Ancient Israel, and Their Neighbors from the Late Bronze Age through Roman Palaestina, ed. William G. Dever and Seymour Gitin (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2003), 87. ↩

-

Israel Finkelstein & Neil Silberman, The Bible Unearthed (Touchstone, 2002), 107. ↩

-

William G. Dever, Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2006), 99. ↩

-

Lawrence E. Stager, “Forging An Identity,” in The Oxford History of the Biblical World (ed. Michael D. Coogan; Oxford University Press, 2001), 100. ↩

-

Niels Peter Lemche, Ancient Israel, A New History of Israelite Society (Sheffield Academic Press, 1988), 90. ↩