A file for the mattocks!?

I was recently looking for an example of a biblical passage that used to be translated one way, but, after an archaeological discovery, was translated a different way. Ideally the discovery would be well documented in the relevant journals, and its implications explained in technical commentaries.

The search didn’t take long…

An obscure passage in I Samuel

Jonathan’s victory at Michmash in I Samuel 14 is set against a background of an Israelite population unable to create or maintain metal weapons – the Philistines didn’t allow it. This situation is described at the end of chapter 13 with the rather pathetic note that, as the King James Version translates it,

1 Sa 13:19–21 Now there was no smith found throughout all the land of Israel: for the Philistines said, Lest the Hebrews make them swords or spears: 20 But all the Israelites went down to the Philistines, to sharpen every man his share, and his coulter, and his axe, and his mattock. 21 Yet they had a file for the mattocks, and for the coulters, and for the forks, and for the axes, and to sharpen the goads.

A pretty sorry situation. Thankfully though, at least they were able to do some of the maintenance at home – they were allowed files for sharpening various farming implements, saving them the hassle of visiting the Philistines for the more trivial work… or so the KJV would have us believe.

We now get to the point of this post – the word whose translation was changed after an archaeological discovery. It’s in verse 21.

The Hebrew

The thing is, the Hebrew underneath the English translation of verse 21 is pretty tricky. And when I say “pretty tricky”, the verse opens with not one, but two hapax-legomena (“Words which occur only once in the Bible”1), one after the other (highlighted in bold text):

וְֽהָיְתָ֞ה הַפְּצִ֣ירָה פִ֗ים לַמַּֽחֲרֵשֹׁת֙ 2

As McCarter explains, the meaning of the first hapax-legomenon (פְּצִ֣ירָה, “p’tsirah”) remains a mystery3; in modern translations it’s rendered something like “The charge/cost/price was…”4

The second hapax-legomenon (פִ֗ים, “pim”) is the word the KJV translators rendered “file”. Rather like the word that comes before it, translators had no idea what to do with it. Other translations up to the first decade of the 20th century rendered the word either the same way the King James Version had it5, or they took some other guess.6

And so, for centuries, translations of this passage were pure guesswork.

Archaeological discovery

The first step made toward working out the meaning of “pim”, our second hapax-legomenon, was a discovery made during the summer excavation season at Gezer in 1907:

Amongst the season’s discoveries published by excavation director, Stewart Macalister, was a tiny, marble, dome-shaped weight of 7.27 grams, inscribed on which were the Hebrew letters פימ (“pim”).7 The significance of the artefact, at least as far as 1 Sa 13:21 goes, wasn’t realised at the time.

A few years later, in 1914, one E. J. Pilcher published the thoughts of Samuel Raffaeli, a money-changer-turned-antiquities-dealer-turned-travel-agent-turned-Keeper-of-the-Coin-Collection-of-the-Palestine-Archaeological-Museum.8 Raffaeli had been approached by a resident of village of Silwan in Jerusalem wanting to sell a small red stone weight inscribed with the Hebrew letters “pim”, weighing 7.75 grams. Raffaeli quickly made the connection between the “pim” in the biblical text of 1 Sa 13:21 and the “pim” on the weight he held in his hand. Based on this connection he suggested the following translation:

“And the payment was a payam for the mattocks and for the coulters, and a third of a shekel for the axes, and to sharpen the goads.”9

The word “payment” was a guess, as it remains to this day, but since the context is one of a weight it’s a pretty sensible guess.

The important point is this: “pim” could now be translated based on hard evidence, not just guesswork.

Effect on Bible translations

The discovery, linking “pim” with a weight, was picked up by bible translators very quickly indeed.

Only 3 years after Raffaeli’s thoughts were published in Palestine Exploration Quarterly, the Jewish Publication Society of America published The Holy Scriptures according to the Masoretic Text10 in 1917 and translated the verse in question,

“And the price of the filing was a pim for the mattocks…”

That’s a pretty short lag between archaeological discovery and influence on a bible translation.

Several decades later the Revised Standard Version included “pim” in its 1952 translation, removing “file” altogether:

“…the charge was a pim for the plowshares and for the mattocks…”

Now, instead of Israelites being able to do the maintenance of some of their farming implements at home, they can’t do any of it. There’s no more “Yet they had a file…” – the Israelites need to go to the Philistines for everything. That’s an important difference.

Further discoveries and clarification

Though “pim” is an improvement on “file” (!), it’s still not all that meaningful.

As usual, further discoveries helped to clarify things a little. Over time, more and more “pim weights” were discovered all over the Holy Land. Here just three of the more well known sites where excavators found them:

Having so many pim weights available for analysis, the relevant scholars found that they all weighed pretty much the same so they were able to confirm what Pilcher first claimed back in 1914, namely that:

“A pim, as we have seen, was the name for 2/3 shekel weight, or a little more than 14 oz.”14

Dictionaries, lexicons, and encyclopaedias started listing the same information:

- Dictionary of Classical Hebrew: “equivalent to two thirds of an Israelite shekel”15

- HALOT: “measurement of weight, two-thirds of a shekel”16

- The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, Volumes 1–4 (Glossary): “ancient Judean weight, probably 2/3 of a shekel”

- AYBD: “It is not impossible that it represents ‘two-thirds’ of the ‘shekel’ norm in the 11–13 gram range”17

Now practically certain that a pim weight represented two thirds of a shekel, translators started using that language:

- NIV (1984): “The price was two thirds of a shekel for sharpening plowshares…”

- NRSV (1989): “The charge was two-thirds of a shekel for the plowshares…”

- NASB (1995): “The charge was two-thirds of a shekel for the plowshares…”

- ESV (2016): “and the charge was two-thirds of a shekel for the plowshares…”

Is that an improvement on “pim”? Not everyone walks around with shekel-to-ounce/gram conversion tables in their head allowing them to read this passage without needing to check the footnotes/open a commentary. But, at least shekel is a common term in scripture that most bible readers have come across before and so have something to compare our passage’s “two thirds of a shekel” to.

Zooming out a little, it’s worth pointing out that the translation “The charge was two-thirds of a shekel for…” begins with a guess (“charge”), and continues with words that simply aren’t in the underlying Hebrew at all (“two-thirds of a shekel”).

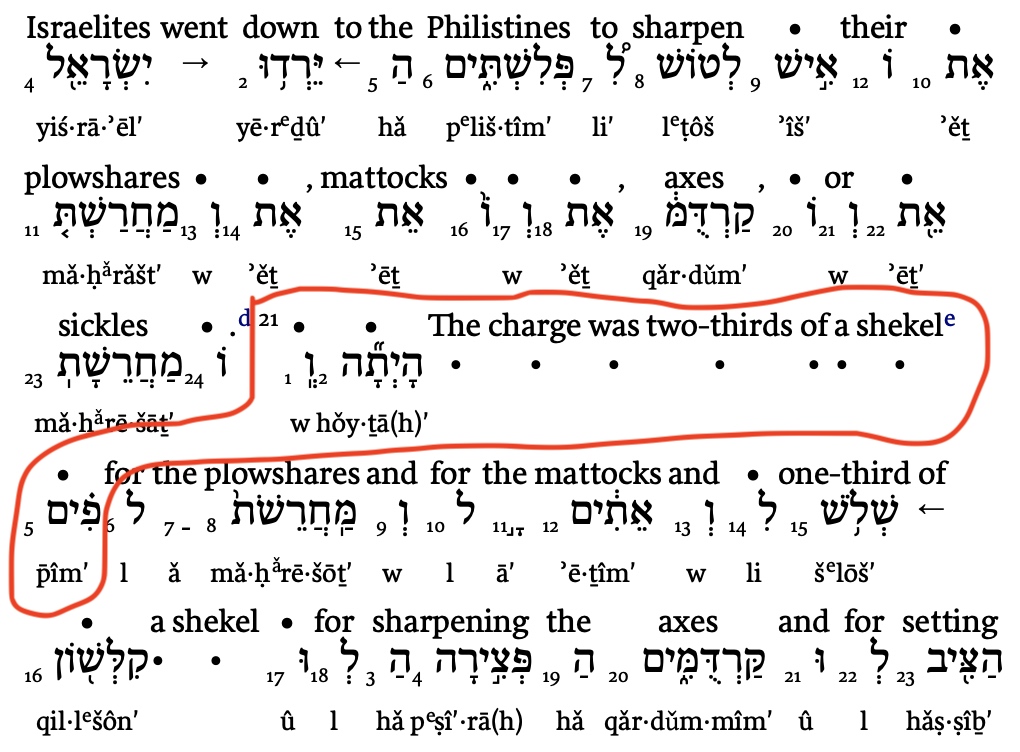

In fact, the example of 1 Sa 13:21 is a case where the most meaningful translation is so foreign to the underlying words that you’d be forgiven for thinking that creators of interlinear bibles must have had some sort of stroke:

And yet “The charge was two-thirds of a shekel for…” is a pretty accurate translation. Its only real flaw is that it doesn’t let the reader know that 2/3rds of a shekel was an exorbitant price to pay for the services the Philistines delivered.1819

Conclusion

So, this is all pretty interesting, at least if you’re me. Though I’ll admit that it might be a bit niche, this translation-by-archaeological-discovery is quite instructive. There are quite a few things this exercise can teach us:

- There are words in scripture that no one knows the meaning of

- It’s not unheard of for scholars to simply guess at the meaning of some words

- Archaeological discoveries can shine a light on text that would otherwise remain beyond our comprehension

- Sometimes “word-for-word” translation doesn’t give the reader the sense of a passage

- Sometimes the best translation is one that doesn’t translate the original language at all but substitutes something altogether different to what a “word-for-word” translation would allow

- Throw away your Strongs Concordance

Featured image

- My (terrible) photo of three weights in the Israel Museum; the middle one is a pim weight discovered at Tel Arad.

Footnotes

-

Frederick E. Greenspahn, “Hapax Legomena,” The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary (New York: Doubleday, 1992) 54. ↩

-

Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, electronic ed. (Stuttgart: German Bible Society, 2003), 1 Sa 13:21. ↩

-

“The word is otherwise unknown, and the present translation is a guess from context.” P. Kyle McCarter Jr., I Samuel: A New Translation with Introduction, Notes and Commentary, vol. 8 of Anchor Yale Bible (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2008), 238. ↩

-

So NRSVue, CEB, ESV, NET, NIV. ↩

-

So ASV (1901), Young’s Literal Translation (1862). ↩

-

Darby Bible (1890): “…when the edges of the sickles…” ↩

-

R. A. Stewart Macalister, “Fifteenth Quarterly Report on the Excavation of Gezer,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly 39.4 (1907): 266-267. https://biblicalstudies.org.uk/pdf/pefqs/1907_04_254.pdf ↩

-

Plicher, E. J., “Notes and Queries,” Palestine Exploration Quarterly 46.2 (1914): 99. https://doi.org/10.1179/peq.1914.46.2.99 ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Jewish Publication Society of America, Torah Nevi’im U-Khetuvim. The Holy Scriptures according to the Masoretic Text. (Philadelphia, PA: Jewish Publication Society of America, 1917) ↩

-

Moshe Dothan, “Ashdod,” The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land (New York; London; Sydney; Tokyo; Singapore; Toronto; Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society & Carta; Simon & Schuster, 1993) 100. ↩

-

McCown, Chester C., Tell en-Naṣbeh: Excavated Under the Direction of the Late William Frederic Badè, Vol. 1: Archaeological and Historical Results (1947), 163-164. https://hdl.handle.net/1813/103953 ↩

-

Dever, William G., “Iron Age Epigraphic Material from the area of Khirbet el-Kom,” Hebrew Union College Annual 40/41 (1969-1970): 180. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23503260 Dever, William G., “Iron Age Epigraphic Material from the area of Khirbet el-Kom,” Hebrew Union College Annual 40/41 (1969-1970): 180. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23503260 ↩

-

Scott R. B. Y., “Weights and Measures of the Bible,” The Biblical Archaeologist 22.2 (1959): 40. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3209306 ↩

-

Clines, David J. A. (Sheffield, 1993) Dictionary of Classical Hebrew, Vol. 6, 682. ↩

-

Ludwig Koehler et al., The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1994–2000), 926. ↩

-

Marvin A. Powell, “Weights and Measures,” The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary (New York: Doubleday, 1992) 906. ↩

-

“Virtually all versions leave uncertainty in the minds of the reader as to whether the charges of the Philistines were reasonable or exorbitant. This would not have been a question to the original readers and hearers. They would have known that the prices were unreasonably high.” Roger L. Omanson and John Ellington, A Handbook on the First Book of Samuel, UBS Handbook Series (New York: United Bible Societies, 2001), 268. ↩

-

“Since the customer had no other option, a high price could be asked.” Joyce G. Baldwin, 1 and 2 Samuel: An Introduction and Commentary, vol. 8 of Tyndale Old Testament Commentaries (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1988), 114. ↩