The Merneptah Stele: Beyond Apologetics

The inscription on the Merneptah Stele is well known for containing the oldest mention of “Israel” outside the Bible. It’s frequently brought up by apologists as proof for the existence of the Israelites in Canaan and therefore of the historical reliability of the Old Testament. But, dig a little deeper and the sentence that “Israel” appears in will prompt us to look at how the Bible employs the language of annihilation; a common feature of ancient texts that doesn’t work in the way we modern laypeople expect it to. When we become aware of it we’ll know to look out for it and interpret it in the way the original writers used it - not as statements of fact, but as hyperbole.

NB: This post is available as a youtube video.

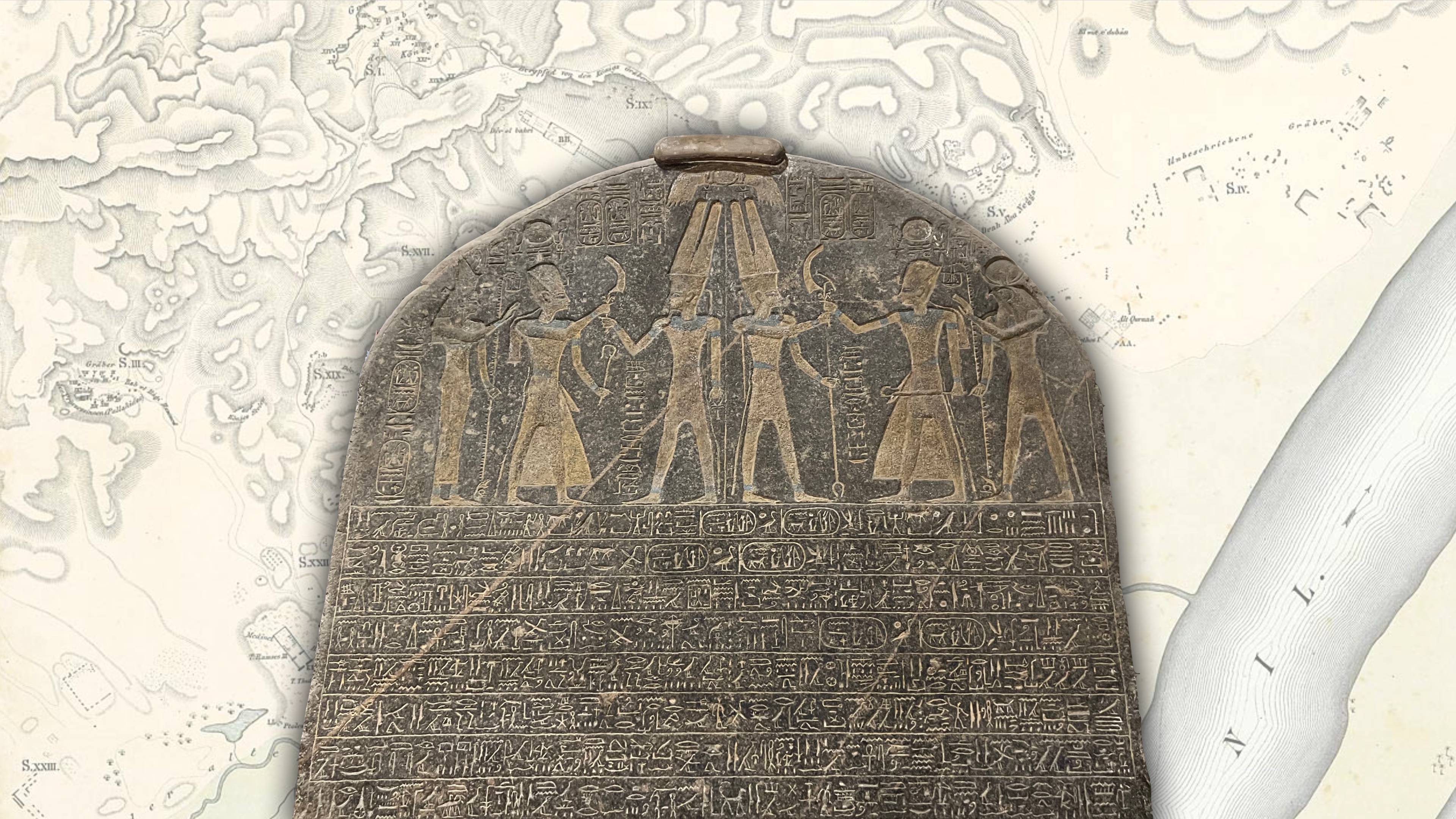

The Merneptah Stele is well known in apologetic circles as the inscription that contains the oldest mention of “Israel” outside the Bible. It’s often cited to “prove” the historical accuracy of biblical books like Exodus, Deuteronomy, Joshua, and Judges. But, just like we saw with the Tel Dan Stele in previous videos in this series, there’s much more to the Merneptah Stele; we just need to get past the shallow level that apologetics often leaves us at and get into the details. When we do that we’ll find that the Merneptah Stele points to scriptures we often read one way, and shows us how to read them a little more thoughtfully.

Discovery

Historical context of the discovery

Unlike the Tel Dan Stele which was discovered at what might have been the height of biblical minimalism, the Merneptah Stele was discovered at the beginning of the era of biblical archaeology. It was a time when polymaths and reverends, funded by wealthy sponsors, would set off, spade in hand, for the lands of the Ancient Near East with the aim of “digging up the Bible”.

How it was discovered

Mortuary Temple of Merneptah

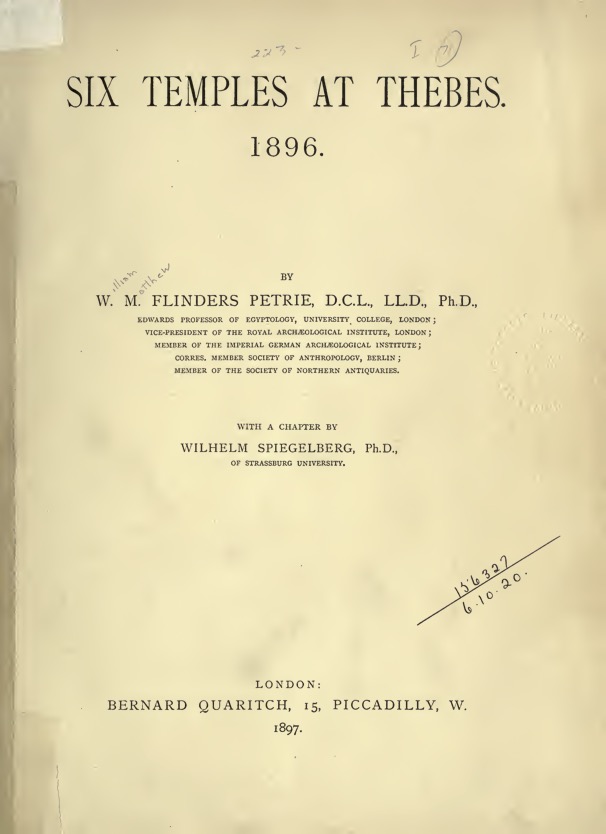

One of these guys was William Flinders Petrie, the Edwards Professor of Egyptian Archaeology and Philology at University College London.

He’d made it his mission to excavate six temples on the west bank of the Nile at Thebes, opposite Luxor, on the other side of the hill from the famous Valley of the Kings.

According to his journal, Petrie arrived in Luxor on the 10th of December 1895. After a few days staying with a friend, he set up base camp in one of the mud brick store tunnels of the 3200 year old Ramesseum; the mortuary temple of Pharaoh Rameses II. That may sound like a romantic setup, but in his journal he explains that it was so cold in the evenings that he would write his journal “between blankets” – the night December desert is cold.1

Anyway, on December 16th, he got digging.2

Only a few days after Petrie arrived, and maybe a little prematurely, his assistant James Quibell, wrote to James Henry Breasted, the Professor of Egyptology and Oriental History and founder of the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, giving him a status update on how the excavations were going. He wrote,

We hope for papyri, we hope for cuneiform tablets; as yet of course it is early days and we have [found] nothing important.3

That was soon to change – Petrie was about to make what he called his “great discovery”.4

As we’ve said, Petrie was out there digging a series of temples. One of the mysteries he solved was that of the missing temple of Pharaoh Amenhotep III - he’s the Pharaoh you’ll have seen if you’ve been to the British Museum and gone to see the Rosetta Stone - you’ll probably have gone through the door in the image below to get to it. The statue on the right is of that Amenhotep III, found at the site Petrie was excavating.

If you’ve been on a tour of Luxor you may have been to Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple - it’s common for tour buses to stop off at the Colossi of Memnon - they stand in front of what remains of that temple.

Anyway, if you look at a photo you’ll see that much of his mortuary temple is… gone:

Now, it’s gone for a number of reasons, like, earthquakes, and flooding, but the main culprit is our Pharaoh Merneptah.

What Petrie discovered is that in building his own mortuary temple, Merneptah raided Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple for parts.

Because of this looting, Petrie was not a Merneptah fan, and he didn’t pull any punches when it came to describing his work. Referring to Merneptah Petrie wrote,

That beast smashed up all the statues and sculptures of Amenhotep II [sic] to put into his foundations, and wrecked the gorgeous temple behind the colossi for building materials.5

Elsewhere he explained that,

The site of Merenptah’s temple was disastrously dull; there were worn bits of soft sandstone, scraps looted from the temple of Amanhetep [sic] III, crumbling sandstone sphinxes, laid in pairs in holes to support columns.6

So, why did Merneptah do such a bad job? Well, as Reader in Egyptian Archaeology at the University of Liverpool, Professor Ian Shaw explains, the Late Bronze Age collapse began toward the end of Merneptah’s reign when he suffered the first waves of the invasions of the Sea People. He didn’t have the time or resources to replicate his father Ramses II’s grand building projects, and toward the end of his life,

[Merneptah] must have realized that he did not have many years left, however, for his mortuary temple on the Theban West Bank is constructed almost exclusively from blocks removed from earlier structures, particularly the nearby temples of Amenhotep III.7

That’s a decent enough explanation - Merneptah had more pressing things on his mind, like surviving invasion. That would have seemed to him like a good enough excuse to pick apart a mortuary temple belonging to one of his predecessors to throw one together for himself. Still, Petrie remained unmoved, describing the temple as being,

…as bad as anything ever done by Turk or Pope…8

But, it wasn’t all bad. At least not for Petrie.

Discovery of the Stele

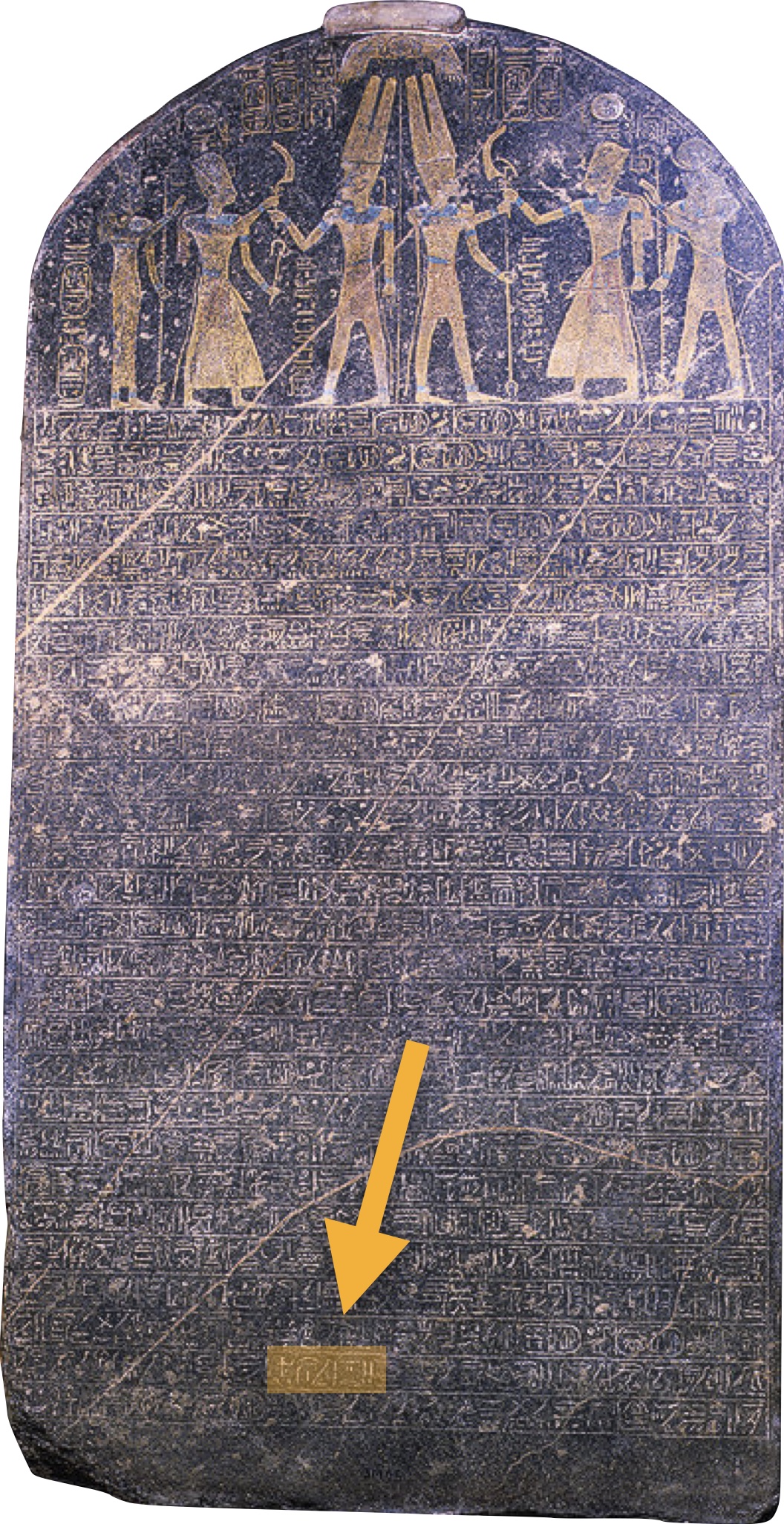

When you enter Merneptah’s Mortuary Temple, you’re standing in what’s called the First Court. When Petrie was excavating it he found at the back left corner of the court (that’s the south-west corner) a large, black, granite stele lying flat on the dirt floor.

The stele was over 10 foot long, over 5 foot wide, and more than a foot thick. It clearly used to stand up straight, but had toppled over at some point during the 3,100 years between Merneptah building the Temple, and Petrie’s arrival. Petrie didn’t know it, but this stele was going to be the highlight of his expedition, and the highlight of his career.

On the upward facing side they found an inscription written by Amenhotep III describing his various building projects including his mortuary temple, the Luxor temple, and the third Pylon at Karnak.9

Clearly, the stele was one of the many items Merneptah had looted for his mortuary temple.

Petrie had the ground below the stele shovelled out, creating a small space to crawl into. On the underside he found another inscription, this time by Merneptah, but he couldn’t read much of it, because, as he wrote in his diary,

“…[the inscription] can only be seen a few inches from one’s nose as one lies under the stone…”10

Transcription and translation

Working alongside Petrie was Dr Wilhelm Spiegelberg, who later became Professor of Egyptology at the University of Munich.

From his notebooks it seems Petrie wasn’t a fan of the Germans, but he described Spiegelberg in relatively glowing terms:

He is the pleasantest German I know… for absence of their usual bumptiousness.11

Spiegelberg was out in Luxor taking copies of inscriptions and translating them, so he helped Petrie out doing the same thing during the excavations. About the day that he had Spiegelberg crawl under the stele to see what he could find, Petrie wrote in his memoirs that the german,

…lay there copying for an afternoon, and came out saying, “There are names of various Syrian towns, and one which I do not know, Isirar.” “Why, that is Israel,” said I. “So it is, and won’t the reverends be pleased,” was his reply.12

The significance of their discovery hit them immediately - it was the earliest mention of “Israel” outside the Bible.

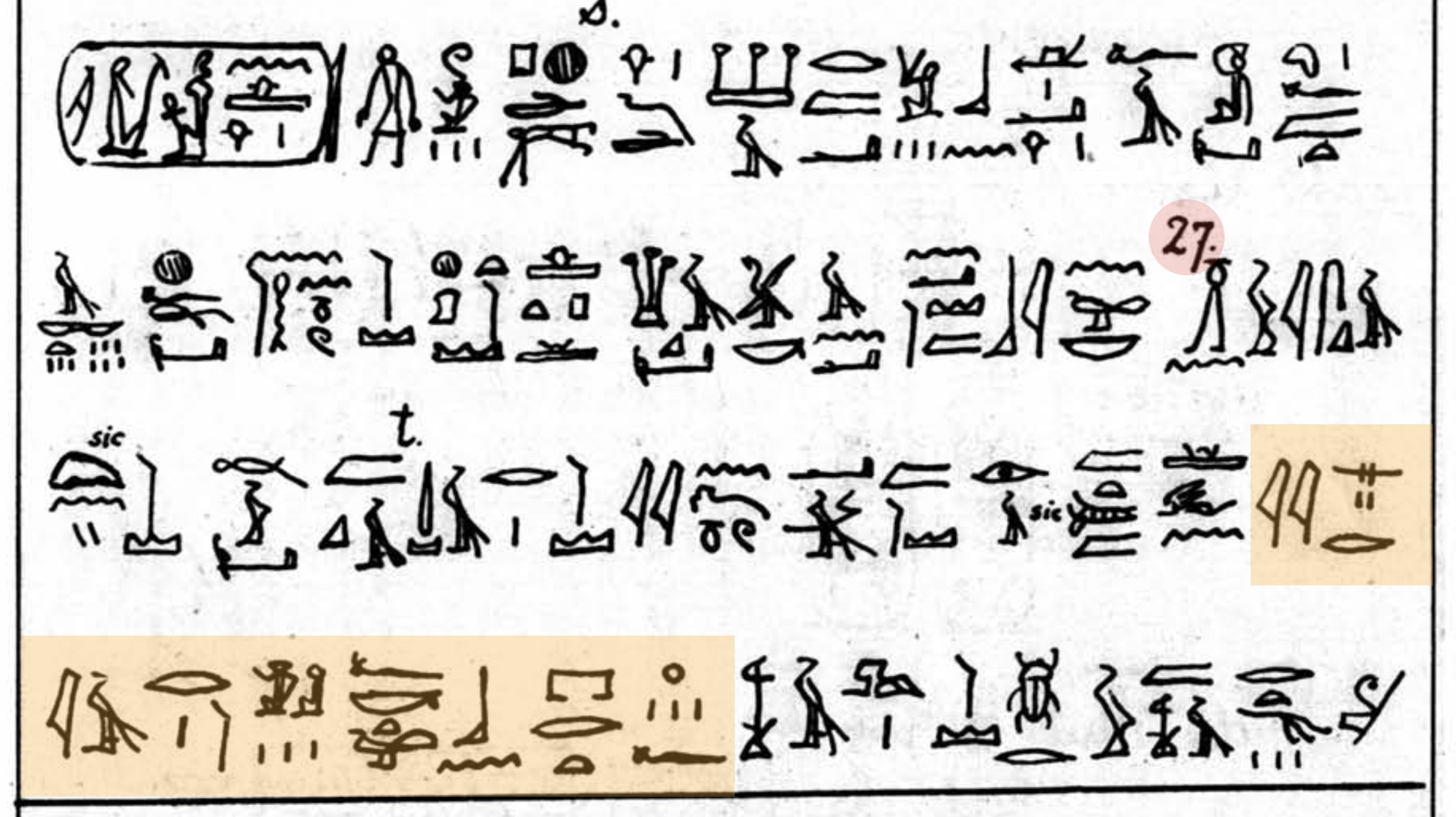

Spiegelberg wasted no time and published his transcription of Mernerpteh’s inscription the same year. Here are the highlighted hieroglyphs from line 27 of the inscription:13

…which read, “Israel is wasted, its seed is not”. And there you go: Israel. On a stele dated around 1208 BCE.

For context, the mention of Israel comes almost at the end of the stele in a list of places and towns that Merneptah had fought in the southern Levant. Here’s how the section reads:

The (foreign) chieftains lie prostrate, saying “Peace.” Not one lifts his head among the Nine Bows. Libya is captured, while Hatti is pacified. Canaan is plundered, Ashkelon is carried off, and Gezer is captured. Yenoam is made into non-existence; Israel is wasted, its seed is not; and Hurru is become a widow because of Egypt. All lands united themselves in peace. Those who went about are subdued by the king of Upper and Lower Egypt … Merneptah.14

The evening of the discovery, Petrie declared,

This stele will be better known in the world than anything else I have found.15

And he was right. He packed his bags on March 4th16 and headed home to England where news of the stele caused a sensation - for all the reasons it’s still promoted by Christian apologists today.

Now, I’m going to get into the apologetic value of the mention of “Israel” and its abuse by some apologists (Christian and otherwise) sometime in the future. For now, we’re going to stick to what Merneptah says about Israel. In the spirit of this series, we’re going beyond apologetics.

Beyond Apologetics

Language of Annihilation

It’s a bit like the Tel Dan Stele’s mention of the “House of David” - the apologetics stuff is interesting enough, but it’s when you look at the rest of the sentence that the famous phrase is in that questions start to appear. So let’s get into it.

Merneptah

As we’ve seen, the Merneptah Stele’s mention of Israel is the phrase,

“Israel is wasted, its seed is not”17

Now, there is plenty of discussion about what Merneptah meant by “its seed is not”,18 but we’re not going to get into that in any detail other than to say that what happened to the “seed” either means that “Israel” was completely wiped out down to the last man, woman and child, or, that their crops have been completely destroyed such that the few Israelites who survived the battle with Merneptah would die from starvation. The end result is the same: as Professor and Chair of the Religion department at Brandon University in Canada, Kurt Noll explains,

…Merneptah claims to have utterly annihilated these people.19

Now, we don’t need the Bible to know that Merneptah’s boast was nothing but wild exaggeration. Even with all the complication about working out precisely who Merneptah’s “Israel” refers to, we find Israel mentioned on the Tel Dan Stele (as we saw in the last video), we also find Israel mentioned on the Mesha Stele (which we’ll cover in a future video), and they’re mentioned on the Kurkh Stele of Shalmaneser III. Whoever “Israel” was… they seemed to have survived whatever Merneptah did to them just fine.

So, why did Merneptah claim to have annihilated “Israel”? Especially since anyone travelling from Egypt along the main trade route up the Levant would know that Israel was doing just fine? Well, as Professor of Hebrew Bible and Old Testament at Rhodes College, Steven McKenzie explains,

This statement is an exaggeration for propaganda purposes.20

If Merneptah’s claim is read as a statement of fact, it’s clearly false. It’s quite clearly exaggeration - Israel was not wiped out; as we’ve seen they lived to fight another day.

In fact, it’s more than just exaggeration. As Noll writes,

The rhetoric of this inscription is the usual boastfulness that one expects from a proud king of mighty Egypt. In fact, it is the language of cliché… the poem consists of sweeping generalizations quite typical of pharaonic bluster, the kind of text that makes it all but impossible to determine what events gave rise to the hyperbole.21

And that’s the point - Merneptah’s boast is not an isolated case, this is just how rulers wrote. It’s cliché.

Mesha

In fact, the next time we find mention of “Israel” in the historical record is in an inscription by a guy named Mesha, the ruler of the Moabites, claiming to have “wiped out” the Israelites. The inscription, dating from around 830 BCE, states,

…Israel hath perished for ever!22

And these aren’t the only instances of inscriptions claiming to have “wiped out” Israel - it’s kind of a theme, mainly because claims to have “wiped people out” is kind of a theme in ancient writing.

One more example…

Ramses III

A few pharaohs after Merneptah, Ramsesses III came along. By his time the invasion of the Sea People was in full swing. He was taking a beating on every front, particularly in his remaining territories along the coast of what is modern day Israel, or “Djahi” as the Egyptians referred to it.

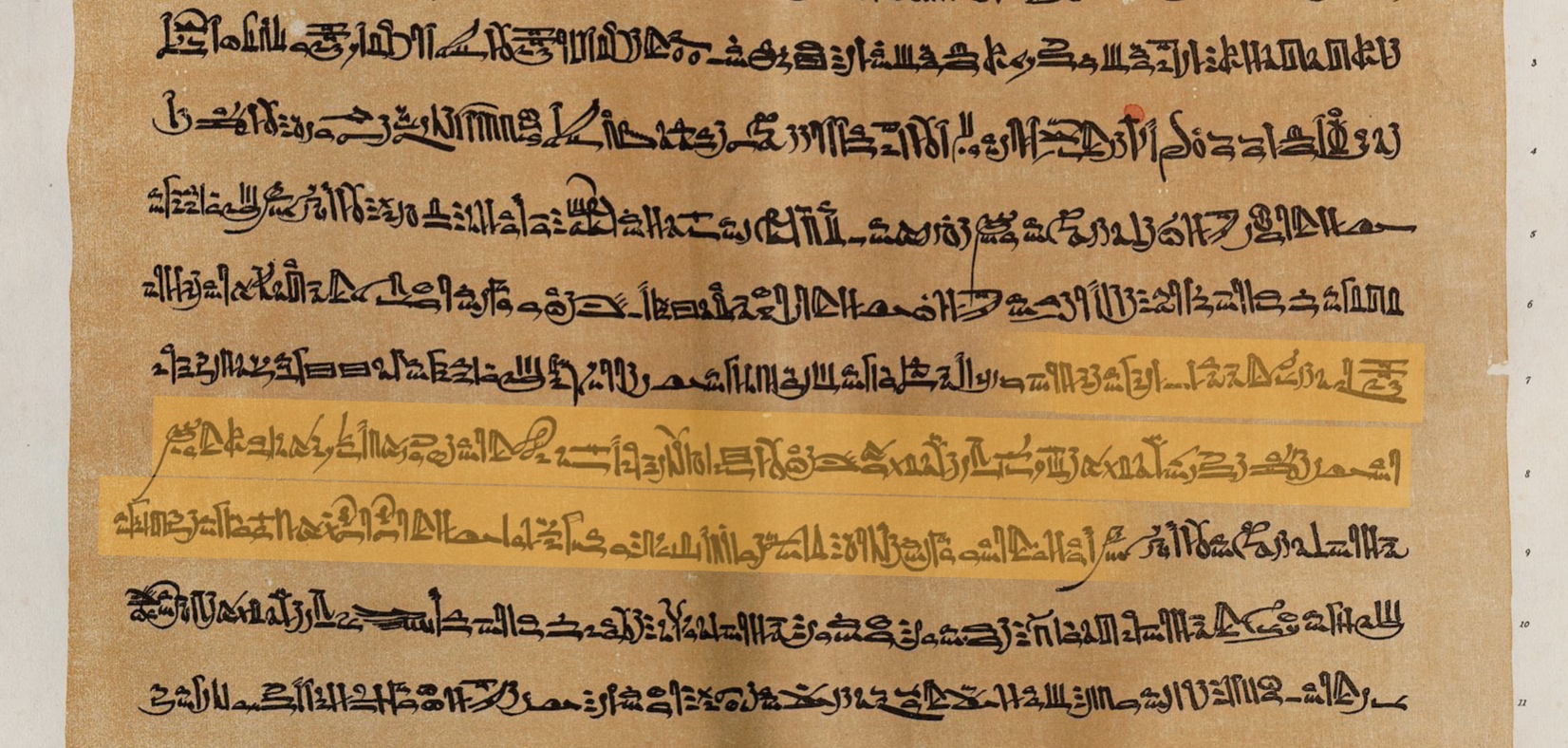

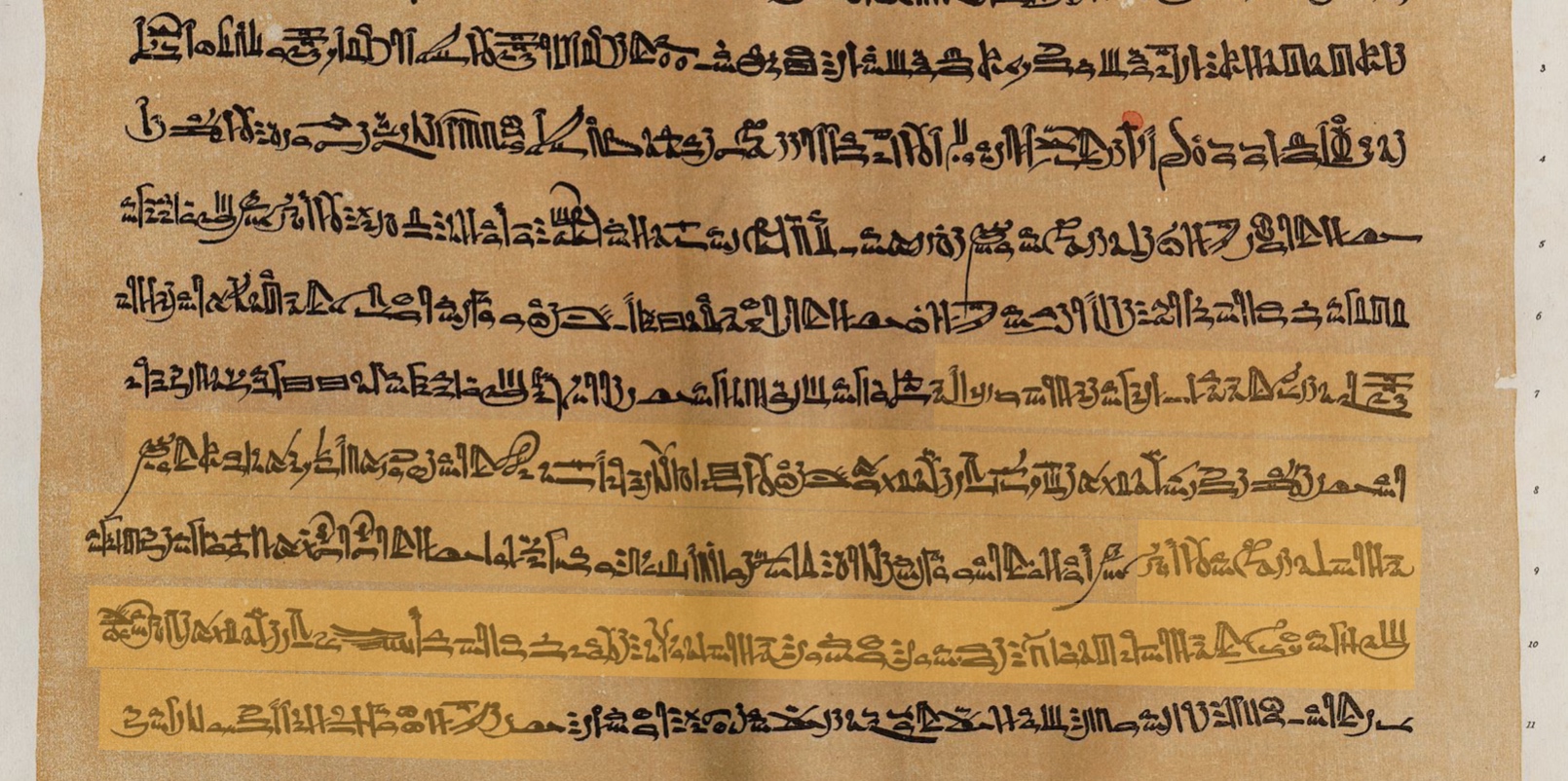

In a document known today as Papyrus Harris 1, stored in the British Museum but sadly not on display, we get a summary of the northern wars against the Peoples of the Sea. In it we read of events in his 8th year,

The Sherden and the Weshesh of the Sea were made nonexistent, captured all together and brought in captivity to Egypt like the sands of the shore. I settled them in strongholds, bound in my name.23

As Professor of History and Humanities at York University in Toronto, Carl Ehrlich explains what’s going on here:

According to Papyrus Harris I, Ramesses, after his victory, settled the Sea Peoples, whom he had “annihilated,” in fortresses24

So, these Sea People “tribes”, the Weshesh and Sherden, were annihilated. They were “made non-existent”. And… then they were settled? So… they weren’t annihilated?

Ramesses III continues,

I destroyed the people of Seir among the Bedouin tribes. I razed their tents: their people, their property, and their cattle as well, without number, pinioned and carried away in captivity, as the tribute of Egypt. I gave them to the Ennead of the gods, as slaves for their houses.25

These people of Seir seemed to have suffered a similar fate - after being completely annihilated and wiped off the face of the earth, they were enslaved and moved somewhere.

Clearly, annihilation isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. It seems being exterminated, wiped off the face of the earth, made non-existent, etc etc, was practically a guarantee that you were going to make a comeback, and probably in style.

SCRIPTURE IS NO DIFFERENT IN THE WAY IT TALKS ABOUT ANNIHILATION.

When it comes to the Bible, we often approach it with the expectation that we can read it at face value and understand it that way. A common approach is to just “read what it says” and accept what we think it’s claiming. We don’t have it in our minds that we’re reading a thoroughly ancient text written in thoroughly ancient ways - we read it like a book written in the past 50 years, something we can just take at face value.

Well, if we’re doing that, that’s a mistake, and the language of annihilation is one of many many examples of where the biblical text works exactly the same as other ancient texts. Let’s take a look.

Annihilation in the Bible

Joshua 10 & 11

We may as well dive in at the deep end - and turn to Joshua 10 & 11, a couple of the most controversial passages in scripture.

I’m hoping to do a series on these two chapters; for now we’re going to look at just one aspect of them: the way they describe the result of the two campaigns they document.

Chapter 10 is often referred to as the Southern Campaign and chapter 11 as the Northern Campaign. Let’s take a look.

Chapter 10 begins with the Israelites down in the Jordan Valley in their base camp at Gilgal. They marched up to Gibeon, defended it in battle against a coalition of Amorite Kings, chased those who retreated down the valley of Ayalon and chased those who survived the hailstones God threw down on them all the way into the southern hill country of Judah.

Toward the end of the chapter we’re presented with a list of cities the Israelites defeated, each one described in a pretty formulaic way including the phrase like “Joshua struck him and his people, leaving him no survivors” (10:33), or, “ he struck it with the edge of the sword, and every person in it; he left no one remaining in it…” (10:30)”.

After the list of towns we get the complete summary of the Southern Campaign:

Jos 10:40 “So Joshua defeated the whole land, the hill country and the Negeb and the lowland and the slopes, and all their kings; he left no one remaining, but utterly destroyed all that breathed, as the Lord God of Israel commanded.”

Now, some people try really hard to make this say something else, but what it’s saying is pretty clear. As Professor of Old Testament at United Theological Seminary, Thomas Dozeman writes,

“…the war is not for the purpose of conquest, but of extermination…”26

And, to emphasise the point that everyone was wiped out, the writer of this passage says that Joshua, “utterly destroyed all that breathed, as the Lord God of Israel commanded.”

Where’s that command? In another “text of terror”; Deuteronomy 20. Here’s what it says:

Dt 20:16–17 “But as for the towns of these peoples that the Lord your God is giving you as an inheritance, you must not let anything that breathes remain alive. You shall annihilate them—[…]—just as the Lord your God has commanded…”

There’s no getting around the way the text describes the result of the Southern Campaign: the southern half of Canaan’s population had been annihilated - exactly as commanded in Deuteronomy.

Let’s turn to the Northern Campaign.

In chapter 11, when the king of Hazor in the north heard about the Israelites’ southern campaign he organised for the kings of the various northern Canaanite tribes to gather together for war. The Israelites went up to fight them, and, of course, they won. Just like the one we find at the end of chapter 10, we get a summary of the northern campaign and what was achieved in it. Here’s how it reads:

Jos 11:19–20 “There was not a town that made peace with the Israelites, except the Hivites, the inhabitants of Gibeon; all were taken in battle. For it was the Lord’s doing to harden their hearts so that they would come against Israel in battle, in order that they might be utterly destroyed, and might receive no mercy, but be exterminated [and, like we saw about the southern campaign], just as the Lord had commanded Moses.”

Again, a complete annihilation. The Canaanites had been exterminated. Utterly destroyed. Who was left in the land? No one. As it says in the next verse,

Jos 11:23 “So Joshua took the whole land… And the land had rest from war.”

Everyone in Canaan was dead. Every last man, woman, child. There was no one left to breathe. Just as the Lord had commanded back in Deuteronomy.

But, it’s not that simple. What’s true for Merneptah’s claim about wiping out the Israelites is true for the biblical claim about the Israelites wiping out the Canaanites. As Noll writes,

Did [Merneptah] really wipe out Israel? In the ancient world, a king often claimed to have annihilated an enemy, yet the enemy in question curiously appears again in later inscriptions!27 K. L. Noll, Canaan and Israel in Antiquity: An Introduction, vol. 83 of The Biblical Seminar (New York: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001), 126.

And that’s what we find in Joshua. Let’s take a look at a couple of examples.

Debir

Back in 10:38-39 we read about what happened to Debir, a town at the southern end of the hills of Judah. Here’s what we’re told:

Jos 10:38–39 “Then Joshua, with all Israel, turned back to Debir and assaulted it, and he took it with its king and all its towns; they struck them with the edge of the sword, and utterly destroyed every person in it; he left no one remaining…”

Pretty conclusive - everyone in the town was completely annihilated. But, what do we read in Judges 1?

The tribes are taking their inheritance, and in verse 11 we find this:

Jdg 1:11–12 From there they went against the inhabitants of Debir (the name of Debir was formerly Kiriath-sepher). Then Caleb said, “Whoever attacks Kiriath-sepher and takes it, I will give him my daughter Achsah as wife.”

Well, if Debir had been annihilated as Joshua 10 claims, there were no inhabitants to go against. Maybe Caleb just wanted rid of his daughter? I mean, there was no one there to stand in the way of anyone who wanted to take Debir, right? Joshua had exterminated the town. So, why are we reading about the “inhabitants of Debir”?

Like Noll said, “the enemy in question curiously appears again in later inscriptions”. And it’s not like Debir is an isolated example from these two chapters. Let’s take a look at Hebron.

Hebron

The passage in Joshua 10 is pretty uncompromising:

Jos 10:36–37 “Then Joshua went up with all Israel from Eglon to Hebron; they assaulted it, and took it, and struck it with the edge of the sword, and its king and its towns, and every person in it; he left no one remaining, just as he had done to Eglon, and utterly destroyed it with every person in it.”

The annihilation was so complete “every person in it” is mentioned twice! There’s no wiggle room here - the passage describes a complete extermination of every single person in Hebron. The. Town. Was. Empty.

What do we find, bizarrely enough, at the end of the Northern campaign?

Jos 11:21 “At that time Joshua came and wiped out the Anakim from the hill country, from Hebron…”

They’re back?! Oh well. Good job they were annihilated again at the end of chapter 11. Phew. But… what do we read in Judges 1?

“Judah went against the Canaanites who lived in Hebron…”

The people of Hebron made it back from annihilation twice, and in quick succession!?

We could go on with more examples, but we don’t need to comb through the text. There’s a passage which puts a spotlight on this whole thing, saving us the trouble.

The nations that God left

We find it in Judges 3:

Jdg 3:1–5 “Now these are the nations that the Lord left to test all those in Israel who had no experience of any war in Canaan… the five lords of the Philistines, and all the Canaanites, and the Sidonians, and the Hivites who lived on Mount Lebanon… So the Israelites lived among the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Amorites, the Perizzites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites…”

Now, if you go back over the list of Canaanite tribes that Joshua annihilated on the northern campaign you’ll find a similar list:

Jos 11:3 “…the Amorites, the Hittites, the Perizzites, and the Jebusites in the hill country, and the Hivites under Hermon…”

So, these nations that Joshua had annihilated are specifically stated as having been left there by God as battle training for the Israelites? And that instead of annihilating the Canaanites the Israelites lived among them?

This is all very reminiscent of Merneptah’s bold claims to have wiped out the Israelites. He claimed to have wiped them out, but he’d done no such thing. Turns out the same is true of the Canaanite tribes that the Israelites claimed to have wiped out.

Clearly, annihilation in Joshua 10 and 11 isn’t what it seems. The Canaanites weren’t annihilated; they survive in the text in great number. And, even though the Israelites were commanded to wipe them out, we found in Judges that it was God’s intention for Canaanites to remain in the land.

So, that’s “annihilation” in Joshua 10 and 11. Onto our next example…

Amalek

We now go forward in the Old Testament to 1 Samuel to the classic “text of terror” that is 1 Samuel 15. In it we read about how God, speaking through Samuel, instructed king Saul to annihilate the Amalekites. Here’s how that command reads:

1 Sa 15:3 Now go and attack Amalek, and utterly destroy all that they have; do not spare them, but kill both man and woman, child and infant, ox and sheep, camel and donkey.

That’s pretty clear. Kill them all, down to the last man, woman, and child. And their animals. Wipe them all out.

The impetus for this action was a directive found in Deuteronomy 25:19…

Dt 25:19 …when the Lord your God has given you rest from all your enemies on every hand, in the land that the Lord your God is giving you as an inheritance to possess, you shall blot out the remembrance of Amalek from under heaven; do not forget.

So, what did Saul do? Well, the whole point of the narrative is that Saul’s downfall was due to the fact that though he killed all the Amalekites, he hadn’t killed their king - Agag. Here’s what it says a few verses after Samuel’s command:

1 Sa 15:8 [Saul] took King Agag of the Amalekites alive, but utterly destroyed all the people with the edge of the sword.

Those preaching on this passage usually concentrate on Saul’s disobedience in not killing Agag - as is kinda the point of the passage, it’s where the narrator wants the focus to be. What’s often passed over though is the rest of verse eight:

[…Saul] utterly destroyed all the people with the edge of the sword.

With the exception of Agag, the text claims that Saul really had wiped out all the Amalekites. He’d annihilated them. His oversight -not killing Agag- was soon remedied by Samuel, who, as we read a few verses later,

1 Sa 15:33 …hewed Agag in pieces before the Lord in Gilgal.

It’s grim stuff, but when it comes to the Amalekite population, that was the end of them. With Agag’s body parts strewn across the floor, there were no longer any Amalekites. They had been annihilated - Saul had “utterly destroyed all the people” down to the last man, woman, and child.

But, just like Merneptah’s Israel, though Saul and Samuel had “utterly destroyed” the Amalekites down to the last man, woman, and child, we find them reappearing only a few chapters later… and in significant numbers.

Here’s how 1 Sa 30 opens:

1 Sa 30:1–2 Now when David and his men came to Ziklag on the third day, the Amalekites had made a raid on the Negeb and on Ziklag. They had attacked Ziklag, burned it down, and taken captive the women and all who were in it, both small and great; they killed none of them, but carried them off, and went their way.

We’re not going to get into the many questions that arise from the fact that the Amalekites didn’t kill a single Israelite (unlike the Israelites who were supposed to have killed every man, woman, and child) - we’re in the passage to note that not only did the Amalekites survive Saul’s genocide, they appear to have survived in great numbers. There were enough of them to take all the woman and children of Ziklag captive (the soldiers had left for battle with Saul), and, more to the point, take a look at verse 17:

1 Sa 30:17 David attacked them from twilight until the evening of the next day. Not one of them escaped, except four hundred young men, who mounted camels and fled.

There were enough Amalekite soldiers to keep David’s army occupied for 24 hours, and by the end of the battle there were enough survivors on the Amalekite side for the retreat to be made up of 400 men.

Clearly, when Saul “utterly destroyed” the Amalekites, “utterly destroyed” doesn’t mean what we think it means. It seems “utterly destroyed” can mean “definitely not utterly destroyed.”

So much for the annihilation of the Amalekites.

For our final biblical example of where annihilation clearly doesn’t mean annihilation, let’s take a look at my favourite example…

Joshua 10:20

Back in Joshua 10 we have the record of Joshua’s “Southern Campaign”. As we’ve already seen, it includes the battle of Gibeon, the “Long Day”, and the conquest of the cities in southern Canaan. It’s also got a section, from verse 16-27, about 5 Amorite kings being shut in a cave to be dealt with after the Israelites had finished battling the Amorites.

So, Joshua instructs his army to go fight. And, they do. In the next verse we find out how that went:

Jos 10:20–21 When Joshua and the Israelites had finished inflicting a very great slaughter on them, until they were wiped out, and when the survivors had entered into the fortified towns, 21all the people returned safe to Joshua in the camp at Makkedah…

So…

- The enemy was “wiped out”…

- …but in the very same verse, only one phrase on, we find that there were survivors who managed to retreat to their fortified towns.

Now, imagine writing this with the expectation that the reader would understand the phrase “wiped out” in the way we’d understand it, i.e. as annihilation - “utter destruction”. If that’s what you wanted your readers to think you wouldn’t follow “until they were wiped out” in the very same sentence with talk of what the survivors did.

Interestingly, some bible translations fall right into this trap - they try to tone down the “wiped out” bit into something a little less… emphatic.

The NRSV that we’ve been quoting doesn’t shy away from the difficulty. It has “wiped out” next to talk of “survivors”. The same goes for the ESV and NASB. The same can’t be said for the New Living Translation which has,

Jos 10:20 (NLT) They totally wiped out the five armies except for a tiny remnant…

Running “except for” in the same sentence feels like a watering down of the absolutist language of the underlying Hebrew. The New English Translation is worse with its rendering the passage,

Jos 10:20 (NET) Joshua and the Israelites almost totally wiped them out, but some survivors did escape to the fortified cities.

“Almost totally wiped them out”!? That’s just not what the Hebrew says. It doesn’t say “almost wiped out”. It says “wiped out”. I like the NET, but in places it tries too hard to iron out or massage away difficulties for my liking.

You can look at attempts to massage away the weirdness as a positive thing - the translators are trying to make it easy for us laypeople to understand the narrative. The thing about this though is that we’re not reading a translation of the biblical text; we’re reading what someone thinks the biblical text should say. I don’t know about you, but I’m not really interested in that. If the text is not in a genre I’m familiar with then I want to know that, and contradictory statements right next to each other are the kind of clue I want. If the text is weird then I want to know that. Don’t try to hide it from me; just give it to me straight and then explain in a footnote how it ought to be understood.

Ironing out the “difficulties” would be like taking a poem and replacing the rhyming words at the end of each line with words that mean the same thing but that don’t rhyme - the poem would read like prose, hiding the fact from you that the text is actually a poem. And that matters - we interpret poems in a different way to how we interpret prose. Confusing poetry for prose will make you look like a right idiot, so you don’t want a translator doing that to you. So, Joshua 10:20 with its “annihilated! but survivors…” language is too useful to be watered down by translators like the NLT and NET do. You want to know you’re dealing with hyperbole so you don’t start interpreting it literally - as many people do.

In fact, this verse is probably the single most useful one in scripture to show how reading language of annihilation in wooden, literalist ways is to miss something important in the text: hyperbole.

Hyperbole

And that’s really what this video is about - it’s about being mindful when reading the biblical text, watching out for hyperbole, especially when it comes to the language of annihilation. Because if you take those claims at face value, you’re going to end up very confused when supposedly exterminated people reappear in great numbers later in the text.

When Merneptah wrote that he’d annihilated “Israel”, it was, at best, hyperbole. When Rameses III claimed to have annihilated the various Sea Peoples, it was hyperbole. When Mesha writes that he wiped out the Israelites he also was employing hyperbole.

And, as we’ve seen, it turns out that the Bible is no different. It contains hyperbole, particularly around the language of annihilation. This isn’t to try to remove the difficulty of the various difficult passages that talk about annihilation, it’s only to recognise that in those passages we’re almost always dealing with examples of hyperbole, not the boring repetition of historical facts.

- Even though Joshua was said to have wiped out the inhabitants of the promised land, it’s very clear that no such thing happened. It’s hyperbole.

- Even though the Bible says they did, Saul and Samuel didn’t annihilate the Amalekites. Not even close. It’s hyperbole.

- And finally, even though the Israelite army was said to have “wiped” out the Amorite armies, when the very next sentence says there were survivors, it’s clear that the Amorites weren’t wiped out. It’s hyperbole.

Why does this matter? Well, if you’re taking these biblical ancient conquest accounts at face value, you’re going to have certain expectations of the archaeological record. You’re going to expect archaeologists to be digging up remains of huge battles, you’re going to expect wholesale change in the material culture from Canaanite to Israelite… and you’re going to expect annihilated people to not reappear in the text.

None of these things are true. Instead,

- Archaeologists have not found evidence of annihilation - quite the opposite. They’ve found that the people who settled in the Canaanite highlands whose descendants were the biblical Israelites settled pretty much peacefully in areas no one was living in.

- At the relevant sites, archaeologists have found that there’s precious little change in material culture at the beginning of the Israelite period - they’ve found that in the main, the culture of those who took part in the settlement of the country continued the surrounding Canaanite material culture.

- And, when it comes to the text, we find that people who were supposedly annihilated reappear all over the place - the people of Hebron, Debir, the Amalekites, etc.

None of this will be any surprise to people who recognise hyperbole when they see it. They won’t have unrealistic expectations of the archaeological record, so they won’t be bending over backwards to try to make the evidence say what it doesn’t. That’s why, especially when it comes to the several-thousand-year-old biblical text, it’s important to know the genre of what you’re reading. And to know the the genre you need to be reading a proper translation that doesn’t hide the clues from you. And you need a decent study bible or commentary set that’ll inform you about what you’re reading. It’s not enough to just “read the Bible” because the presuppositions you approach the text with almost blind you to what you’re reading. We’re too steeped in our own 21st century, western, legalistic, materialist, stupid culture to understand a text that’s thousands of years old.

So. There you go. The mention of “Israel” on the Merneptah is cool, but the fact that they’re mentioned as having been annihilated is what’s really interesting. Beyond apologetics.

Featured image

- Merneptah Stele, by Onceinawhile (CC-BY-SA-4.0), superimposed on General Karte von Theben, from the Lepsius Projekt (public domain).

Footnotes

-

Petrie MSS 1.13 – Petrie Journal 1895 to 1896 (Thebes) ↩

-

William Matthew Flinders Petrie, “Seventy Years in Archaeology (1932), 171. ↩

-

James E. Quibell (correspondence dated 18th December 1896) in James Henry Breasted, “The Latest from Petrie,” The Biblical World (Feb), Vol. 7, No.2 (1896): 139. ↩

-

William Matthew Flinders Petrie, “Seventy Years in Archaeology (1932), 171. ↩

-

William Matthew Flinders Petrie (correspondence dated 14th February 1896) in James Henry Breasted, “The Latest from Petrie,” The Biblical World (April), Vol. 7, No.4 (1896): 292. ↩

-

Flinders Petrie, Seventy Years in Archaeology (New York, 1932), 171. ↩

-

Ian Shaw, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt (Oxford University Press, 2003), 295. ↩

-

Flinders Petrie, “Egypt and Israel,” The Contemporary Review, May 1896, 619. ↩

-

Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume II: The New Kingdom (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973–), 43–47. ↩

-

Petrie MSS 1.13 – Petrie Journal 1895 to 1896 (Thebes) ↩

-

Petrie MSS 1.13 – Petrie Journal 1895 to 1896 (Thebes) ↩

-

Flinders Petrie, Seventy Years in Archaeology (New York, 1932), 172. ↩

-

Wilhelm Spiegelberg, “Der Siegeshymnus des Merneptah auf der Flinders Petrie-Stele,” Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde, Volume 34, Issue 1 (1896): 1-25. ↩

-

William W. Hallo and K. Lawson Younger, Context of Scripture (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2000), 41. ↩

-

William Flinders Petrie, Seventy Years in Archaeology (New York, 1932), 172. ↩

-

William Flinders Petrie, Seventy Years in Archaeology (New York, 1932), 173. ↩

-

William W. Hallo and K. Lawson Younger, Context of Scripture (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2000), 41. ↩

-

Michael G. Hasel, “Israel in the Merneptah Stela,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (November).296 (1994): 45-61. ↩

-

K. L. Noll, Canaan and Israel in Antiquity: An Introduction, vol. 83 of The Biblical Seminar (New York: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001), 126. ↩

-

Steven L. McKenzie, Introduction to the Historical Books: Strategies for Reading (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge: William. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2010), 50. ↩

-

K. L. Noll, Canaan and Israel in Antiquity: An Introduction, vol. 83 of The Biblical Seminar (New York: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001), 126. ↩

-

James Bennett Pritchard, ed., The Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament , 3rd ed. with Supplement. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 320. ↩

-

James Bennett Pritchard, ed., The Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament , 3rd ed. with Supplement. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 262. ↩

-

C. S. Ehrlich, “Philistines,” Dictionary of the Old Testament: Historical Books (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2005), 786. ↩

-

James Bennett Pritchard, ed., The Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament , 3rd ed. with Supplement. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 262. ↩

-

Thomas B. Dozeman, Joshua 1–12: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, ed. John J. Collins, vol. 6B of Anchor Yale Bible (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2015), 59. ↩

-

K. L. Noll, Canaan and Israel in Antiquity: An Introduction, vol. 83 of The Biblical Seminar (New York: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001), 126. ↩