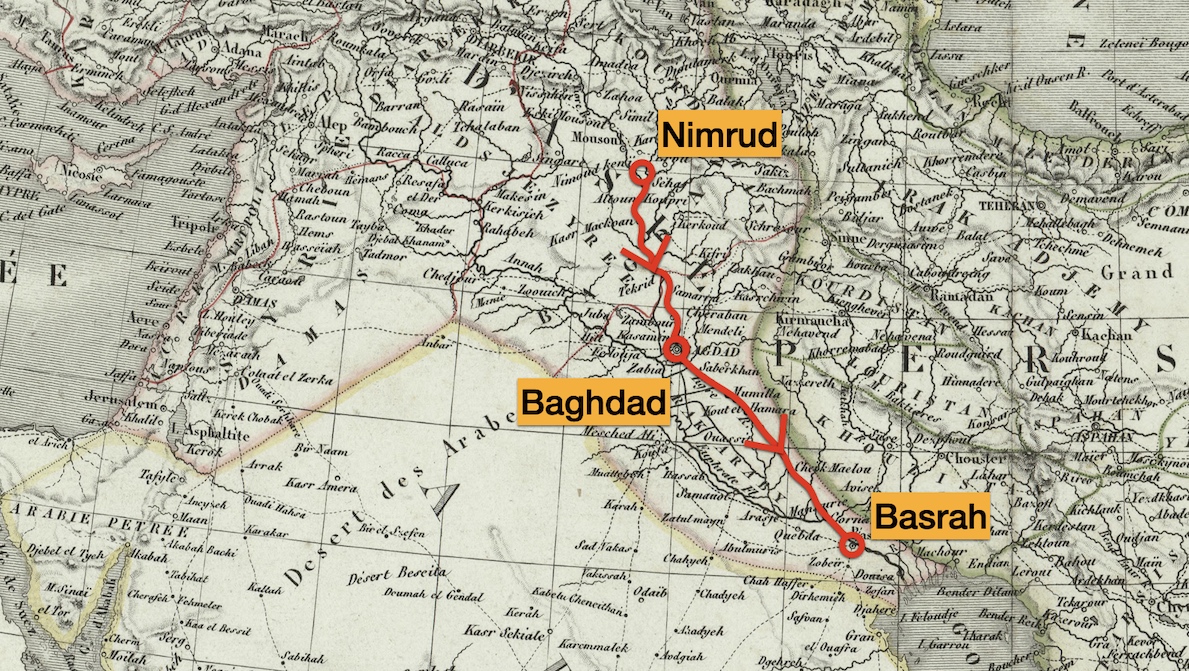

The Black Obelisk’s journey from Nimrud to London

While preparing my next Beyond Apologetics video on the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, I got a bit distracted reading up on how the artefact was transported from Nimrud in Iraq where it was discovered to the British Museum. One minute I’m reading about the trench it was found in, the next minute I’m reading 19th century shipping logs of the East India Company. Since all the info I found was completely inconsequential to the stuff I usually cover in the Beyond Apologetics videos, I decided to split this stuff out into a separate, uber-niche, and super-nerdy post dedicated to the Obelisk’s journey. It should be interesting to about 3 people.

So, why write this up at all? Well, because it’s given me a new perspective: I’ve visited many museums around the world; I’ve seen a bazillion artefacts; I’ve read up on their significance; I’ve made little notes in my bible about the context they add to whatever passage I’m looking at; and I’ve spoken at various churches showing how archaeological artefacts can help us interpret scripture better than we otherwise might.

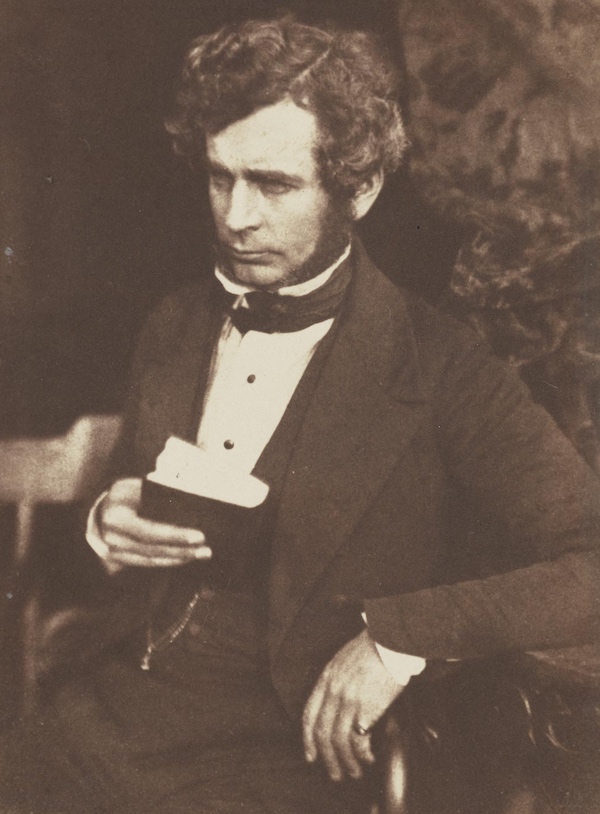

But, I’ve never once considered how these artefacts actually got from where they were found, to the museum they’re displayed in. At least, not until I recently read through Austen Henry Layard’s “Nineveh and its Remains”. The book is pretty wild –the man was a proper adventurer it seems, –a real Allan Quatermain figure– but the bit that piqued my interest was his description of how he transported the obelisk. It’s crazy stuff.

But, as far as Layard’s book goes, as soon as the obelisk is sent from Nimrud the trail goes cold. Wanting a little more detail, I decided to pick up the obelisk’s trail and see how things turned out. And, well, it turns out that it’s a miracle that the obelisk made it to London at all.

Let’s get started.

Discovery

In November 1845, a man whose name is well known to anyone with even a passing interest in Assyriology, arrived in Mosul – a town in modern day northern Iraq, in the area known at that time as “Turkish Arabia”.

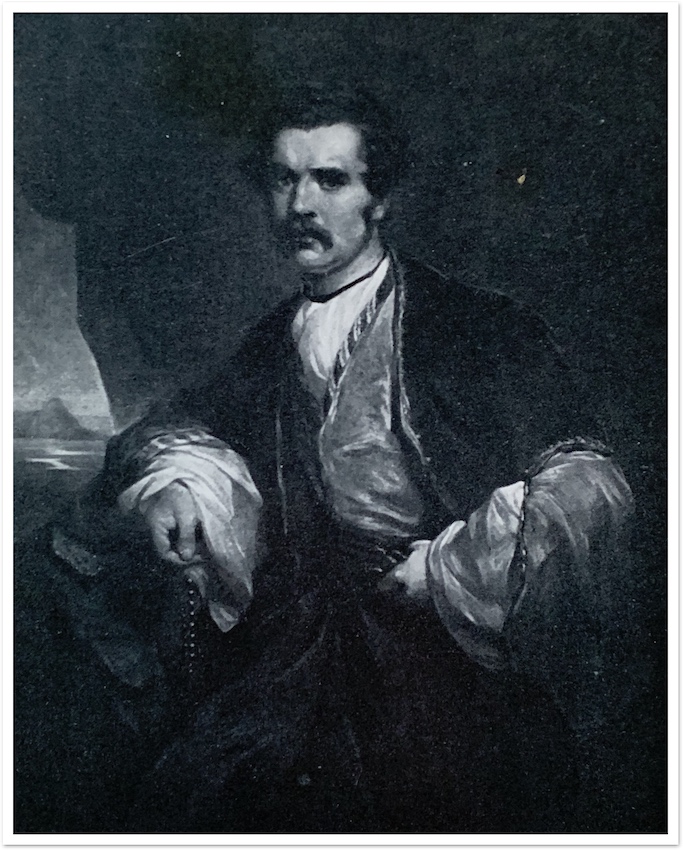

Austen Henry Layard, according to one of his friends, was the man for the task at hand. He was described by one guy as being “excellently fitted for the work of an explorer and excavator, strong, robust, determined, … active, energetic, and inured to hardship by his previous travels in wild regions.”1

And that’s what Layard had come for – to excavate a site he’d come across on his previous trips. Funded by Sir Stratford Canning, the British ambassador to Constantinople2, Layard’s objective was to excavate Nimrud, a site down the river from Mosul that at the time he thought was Nineveh. It would be quite a while before he figured out that Nimrud wasn’t Nineveh, but that’s a different story.

On November 8th 1845, after presenting his credentials to the local government3 and telling the locals that he was sailing downstream to hunt wild boars, Layard hopped on a raft he’d hurriedly built for the occasion, and floated down the Tigris. Around 5 hours later Layard arrived at Nimrud, disembarked, and had a wander around.4

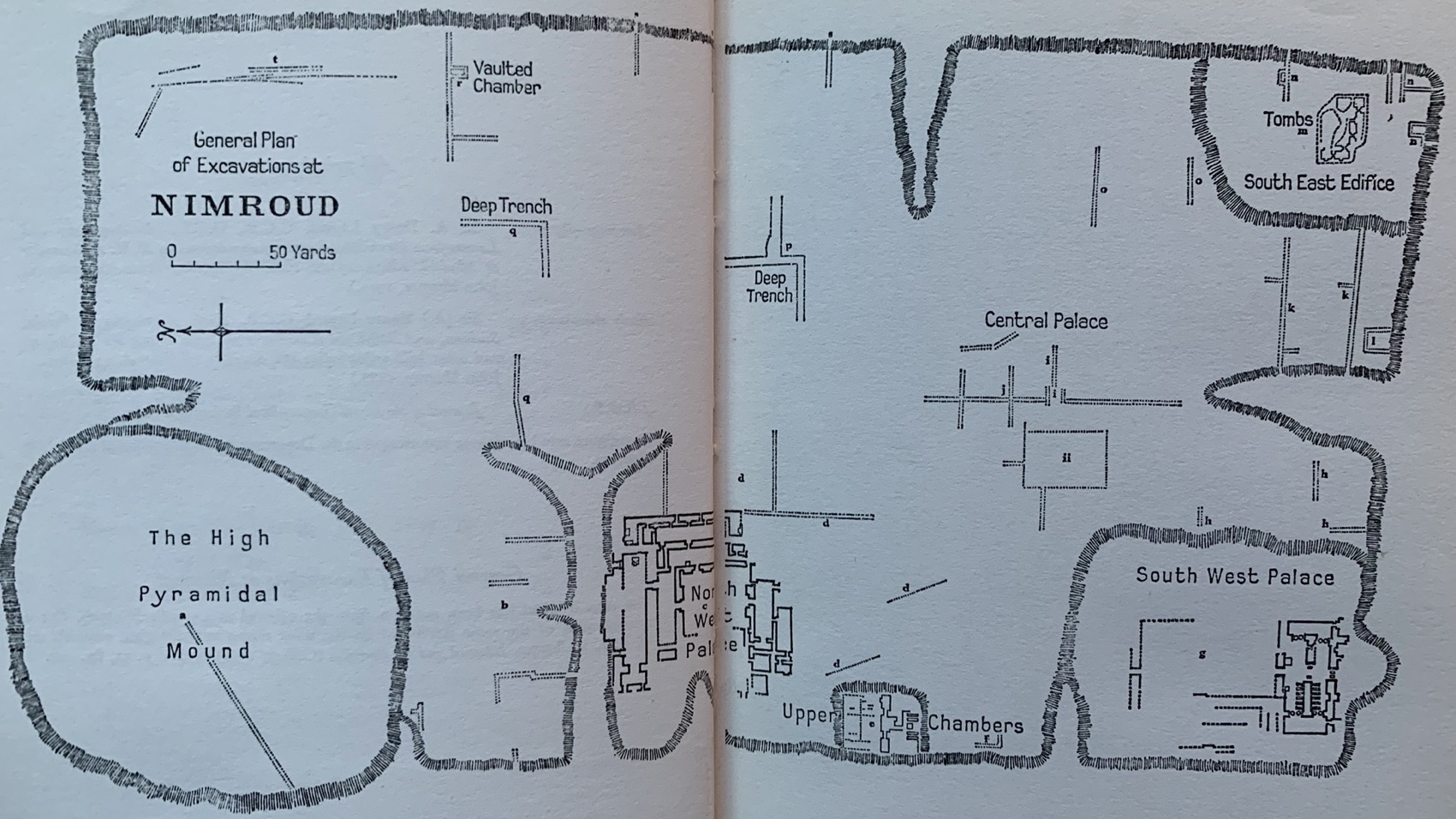

After a few days poking around, he set up camp – you can see it on the following map, very close to the mound of Nimrud where he was excavating.

For several months he and the local workmen he’d hired for the job made great progress, focusing mainly in a couple of areas – excavating what are now known as the North-West and South-West palaces. He also opened experimental trenches all over the mound5 and found some pretty awesome stuff in them too.

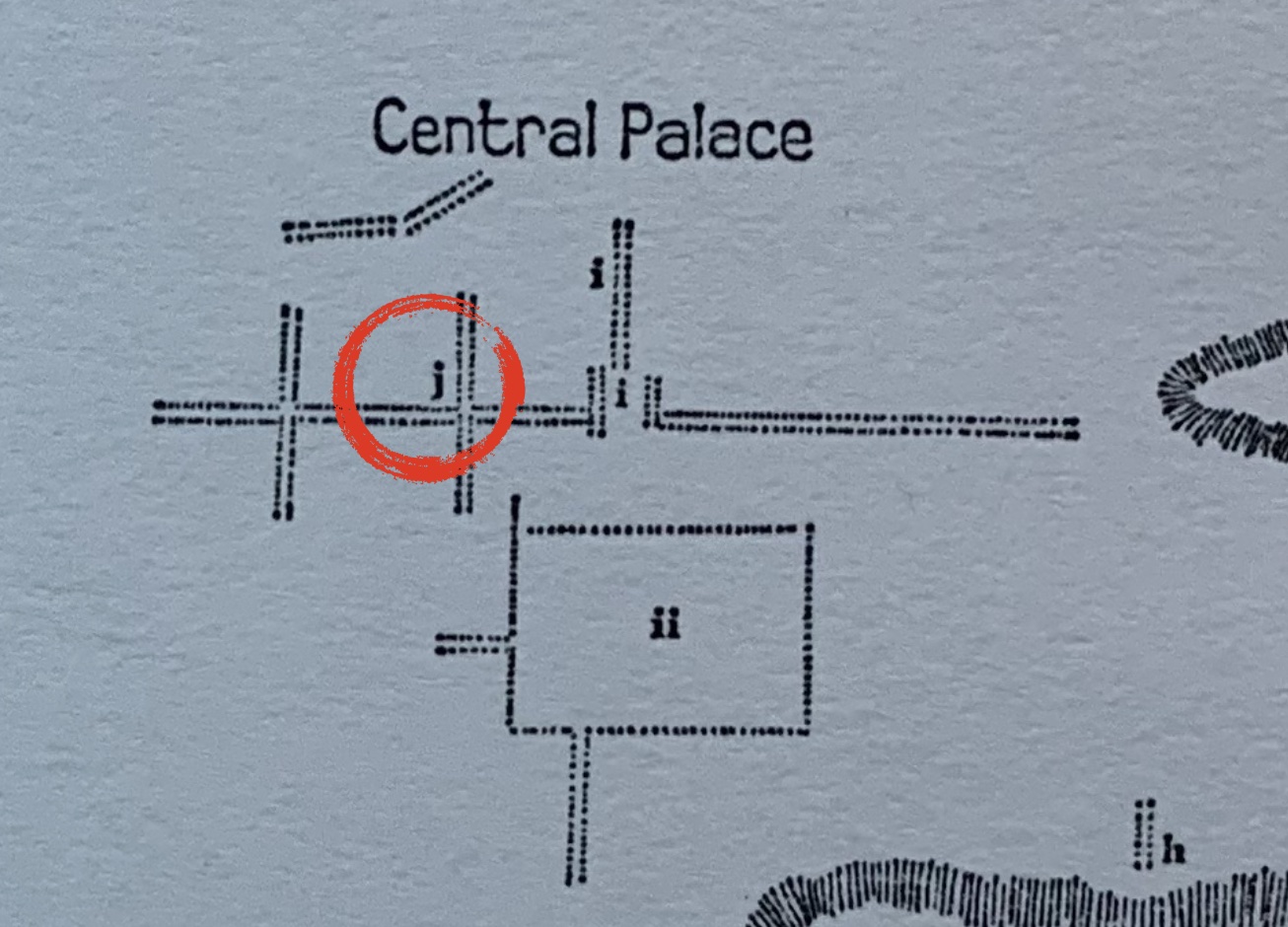

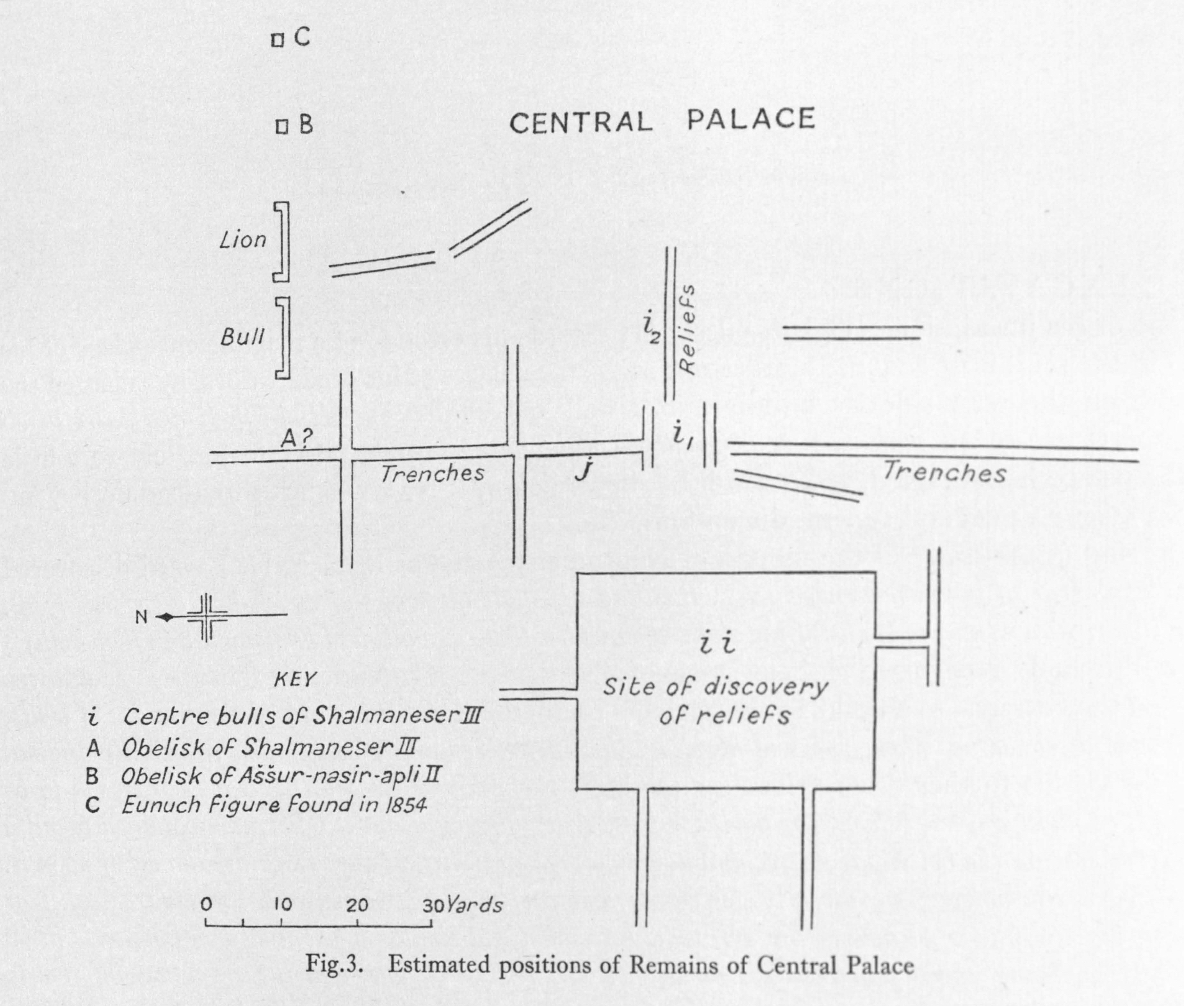

One of these experimental trenches was dug in the “central area” of the mound, marked ‘J’ on Layard’s maps:

There they found “part of a pair of gigantic winged bulls, the head and half the wings of which had been destroyed”.6 Bizarrely, because Layard’s maps weren’t all that accurate, nor was his description of where the “central area” was located on the mound, excavators that came after Layard couldn’t locate these “central area” trenches. It would be more than 125 years after they were first dug that the trenches would be rediscovered in the Polish excavations of 1974-1976’ second season.7

Over the course of his excavations Layard suffered various delays, mainly at the hands of the local authorities. The worst of it was over the summer of 1846 when he was completely stalled, but, after some negotiations Layard was able to get back to it.

On November 1st 18468, he had his working parties start digging at a number of different places on the mound, including back in the trench marked “J” in the “central area” where around the same time the year before he’d found the remains of those two winged bull statues.9 Nothing of any interest was found there, so he had his men dig a trench behind one of the bulls and follow it along for several days. When it reached around 50 feet long, Layard almost gave up on the trench. He let the workmen continue with it while he had business for a day back in Mosul deciding that if they’d still found nothing by the time he returned that he’d give up on the trench.10

After giving his men instructions Layard galloped off for Mosul. He’d hardly gone far at all when, back in the trench, his workmen found the corner of what ended up being the Black Obelisk. They uncovered the 6 foot length of it and the superintendent sent someone after Layard, who turned back straight away. On his return Layard and his men pulled the obelisk out of the trench using ropes, and stood the obelisk upright.11

And, that was the only thing they found in that 50 foot long trench. The excavations run by the British School of Archaeology in Iraq in 1952 dug in what they hoped was the same area of Layard’s “central area” trench but also found nothing.12 The trench produced one obelisk. That’s it.

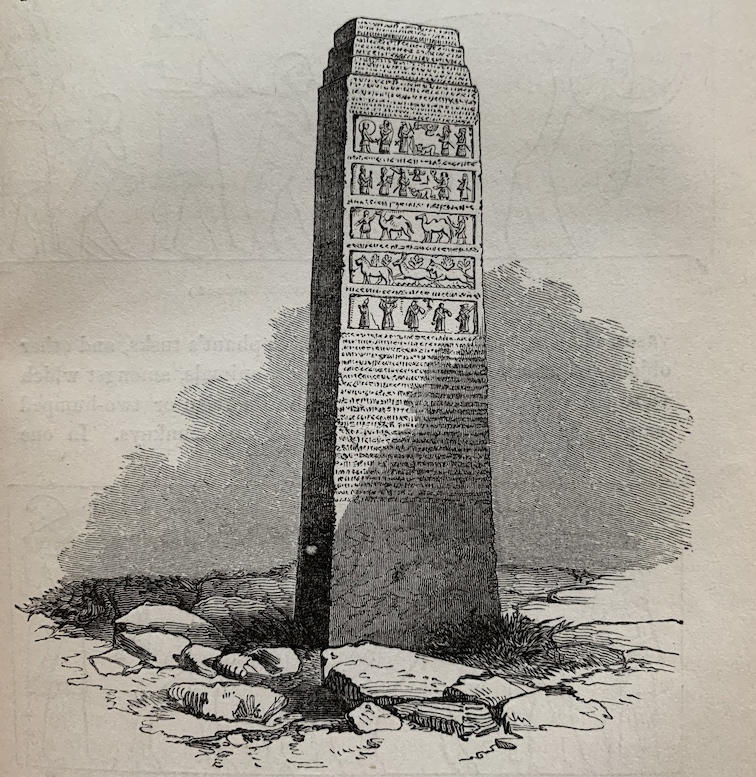

But what an obelisk! In a letter to his aunt Sarah Layard wrote that the “most remarkable discovery”, referring to the obelisk, was “one of the most interesting and unique monuments of antiquity”.13 Layard’s colleague Rawlinson, downriver in Baghdad, who we’ll meet in a couple of minutes, wrote to Layard exclaiming that he considered it, “the most notable trophy in the world and would alone have been well worth the whole expense of excavating Nimrud.”14 So, the obelisk was a big deal, and remains a big deal to this day.

As soon as Layard and his men had yoinked the obelisk out of the trench, he set about taking rubbings of it, as well as sketches which he published a couple of years later in a beautifully produced book, imaginatively named “The Monuments of Nineveh, from drawings made on the spot”.15

After making his sketches, Layard packed up the obelisk ready to be transported with the next batch of artefacts addressed to the British Museum, and, as he explains in his book, “A party of trustworthy Arabs were chosen to sleep near it at night; and I took every precaution that the superstitions and prejudices of the natives of the country, and the jealousy of rival antiquaries, could suggest.”16 He wasn’t taking any chances. The obelisk was not going to get robbed.

From Nimrud to Basrah

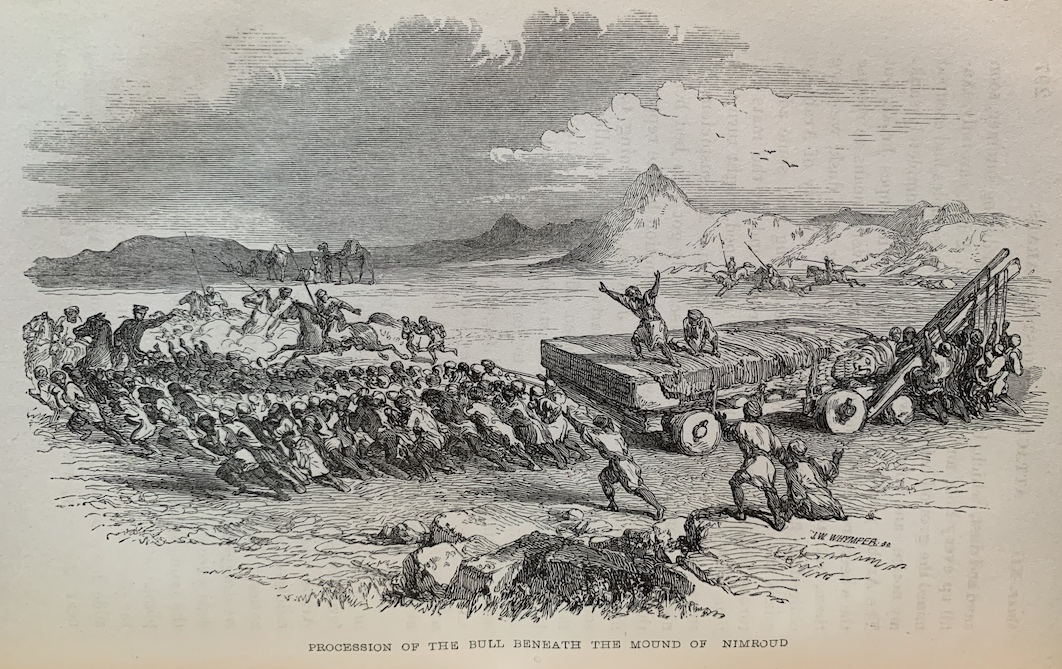

A few weeks later the consignment was ready – Christmas day was the day. In what is the closing scene of his book Layard describes how he had his men load all the artefacts onto what he described as “rotten and unwieldy” buffalo carts that would cover the short distance from the mound of Nimrud to the Tigris river, and how at the river bank he had them loaded onto rafts bound for Baghdad.17

The last line of his book goes like this: “I watched them until they were out of sight, and then gallopped [sic] into Mosul to celebrate the festivities of the season, with the few Europeans whom duty or business had collected in this remote corner of the globe.”18 What a life.

As mentioned previously, this is where the obelisk’s trail goes cold in Layard’s book. Thankfully, at least for this nerd, there’s a whole ton of documentation that illustrates what happened to the obelisk between Nimrud and the British Museum. We’re going to get into that now.

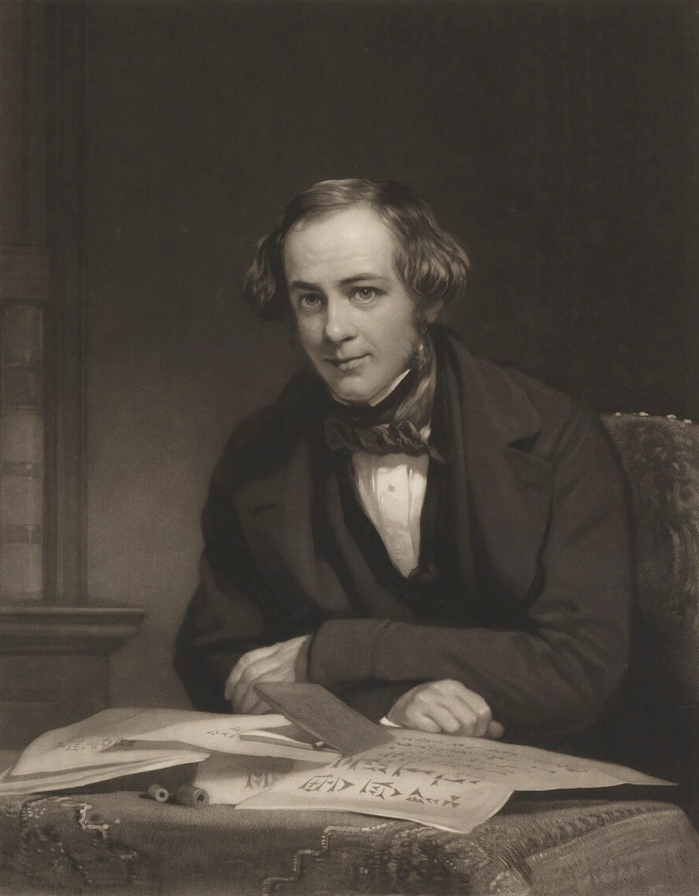

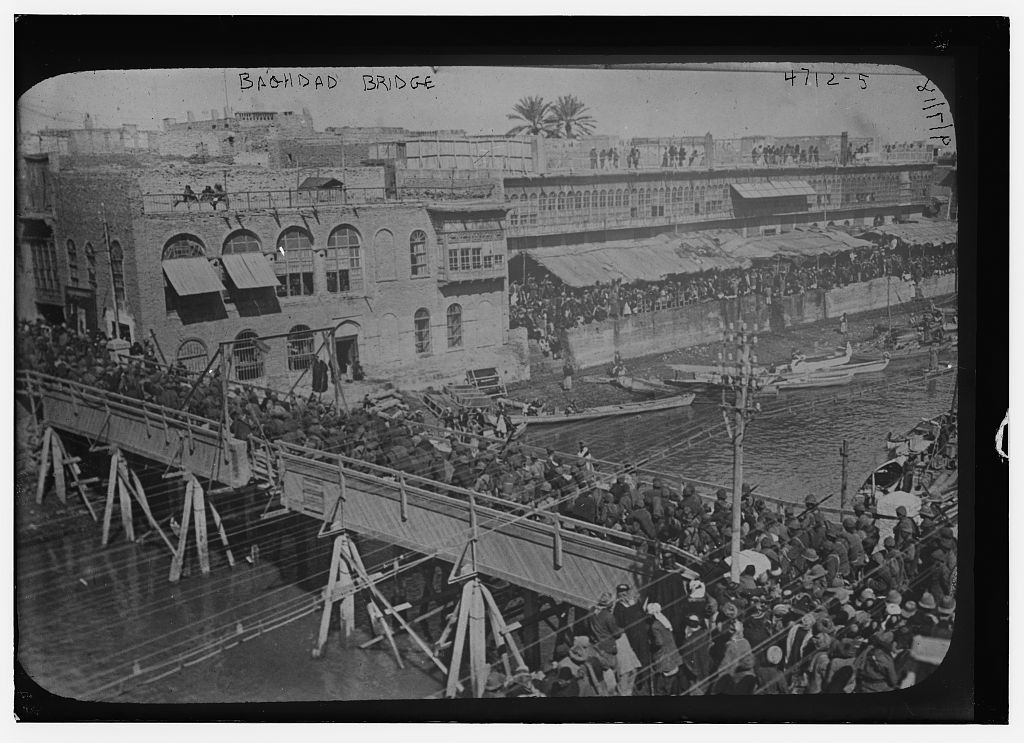

The first stop on the journey was the capital, Baghdad. When the rafts from Nimrud arrived in early January 1847 they were received by Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson, a political agent and employee of the British East India company, stationed in Baghdad. He was also quite the “Orientalist”, and explored ancient sites, copied inscriptions, and worked on the decipherment of cuneiform writing – there’s a bit of intrigue in that last bit, with Rawlinson getting a bit more credit than he actually deserved, but that’s a story for another time.

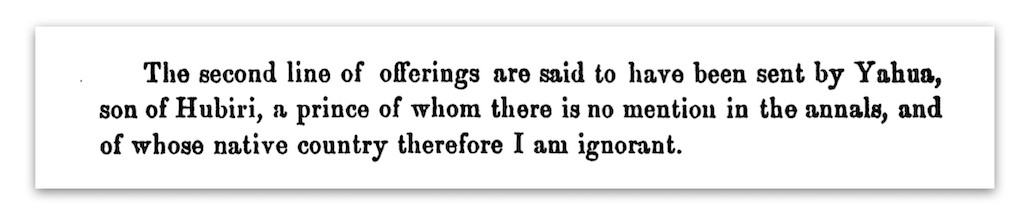

With Rawlinson stationed at Baghdad, he took charge of the artefacts Layard had floated downstream, sending them on to the port city of Basrah. But, before sending them on, Rawlinson took some liberties. British Assyriologist Cyril Gadd writing a couple of generations later tells us that Rawlinson inspected the artefacts “with the interest of one who was conscious that they meant more to him than to any other man living”.19 Rawlinson’s son, in his father’s biography wrote that, “Rawlinson was enjoying the full advantage of free access to the Ninevite treasures on their passage through Baghdad to England… In letters to the Royal Asiatic Society dated January 23, June 19, and November 3, 1847, he began the publication of his views on the subject of the Assyrian alphabet and language, and especially gave an account of the inscription of the famous ‘Black Obelisk’…”20

It does seem like in at least the first of these letters to the Royal Asiatic Society he requested that their contents remain confidential21, but still that’s out-and-out intellectual property theft, and from other stuff I’ve read it seems pretty characteristic of Rawlinson. Not sure that sort of thing would be tolerated in academic circles today…

So, the obelisk’s journey didn’t get off to a good start. But, at least once Rawlinson was done taking his liberties, he did put the artefacts back on “native river craft” and sent them downstream to Basrah, and on arrival in April (1847) they were stored in the East India Company’s naval depot ready for onward shipping.22 And that was the next hurdle.

To Bombay after long delay

Steam ships weren’t really yet a thing, and it would be more than 20 years before the Suez Canal was opened, so to get to London the Obelisk was to take the normal form of global transport in what was known as the Age of Sail – a sailing ship. But to get on a proper sail ship the obelisk first had to make its way to a major port. The closest one to Basrah was 3,000 km away in Bombay, or as it’s known today, Mumbai. So, getting to Bombay was the plan.

But, for now, the obelisk along with the rest of the artefacts it floated down river with, was stuck in Basrah. As Gadd notes, “conveying [the obelisk] farther, on the way to Bombay or England, proved a difficult problem,”23 because “trade was almost completely stagnant in the Gulf at that time, and the visit of any European vessel to Basrah a rarity.”24 So the artefacts collected dust in some storage unit in Basrah’s East India Company naval depot. Occasionally a ship large enough to transport the artefacts came into port, but for one reason or another the instruction to transport the artefacts wasn’t received by the captain, or was just plain ignored.25

Spring turned into summer; autumn came and went, and by December Layard was back in London having travelled via Constantinople, Italy, and Paris.26 In the same month, out of exasperation I presume, Rawlinson came down from Baghdad to Basrah. In what was great timing, while he was there the East India Company Sloop-of-War Clive arrived at the port. Rawlinson instructed the captain to transport the artefacts to Bombay who responded that he’d do the best he could. But, Sloops-of-War weren’t big ships and he was only able to take 20 cases, and, only as far as Bushehr in what today is modern Iran – a measly 350km of the 3000km journey to Bombay.27

At least, the obelisk was finally on its way – a good job too as the next shipment of artefacts wouldn’t take place for another year!28

As the captain of the Clive agreed, they transported the cases as far as Bushehr, unloading Layard’s artefacts there. Fortunately for Layard, Senior Naval Officer Captain William Lowe had sailed into Bushehr harbour on the 1st of January 1848 after a successful mission retrieving a couple of boats that had been stolen by some local sheikh.29 Layard’s artefacts, including the obelisk, were loaded onto Captain Lowe’s ship; another Sloop-of-War named the Elphinstone.

An obscure passage in Volume 2 of Charles Rathbone Low’s History of the Indian Navy explains that sometime in January the Elphinstone set off with the obelisk on board, arriving in Bombay sometime later in January.30 (Not the same Low as captained the Elphinstone)

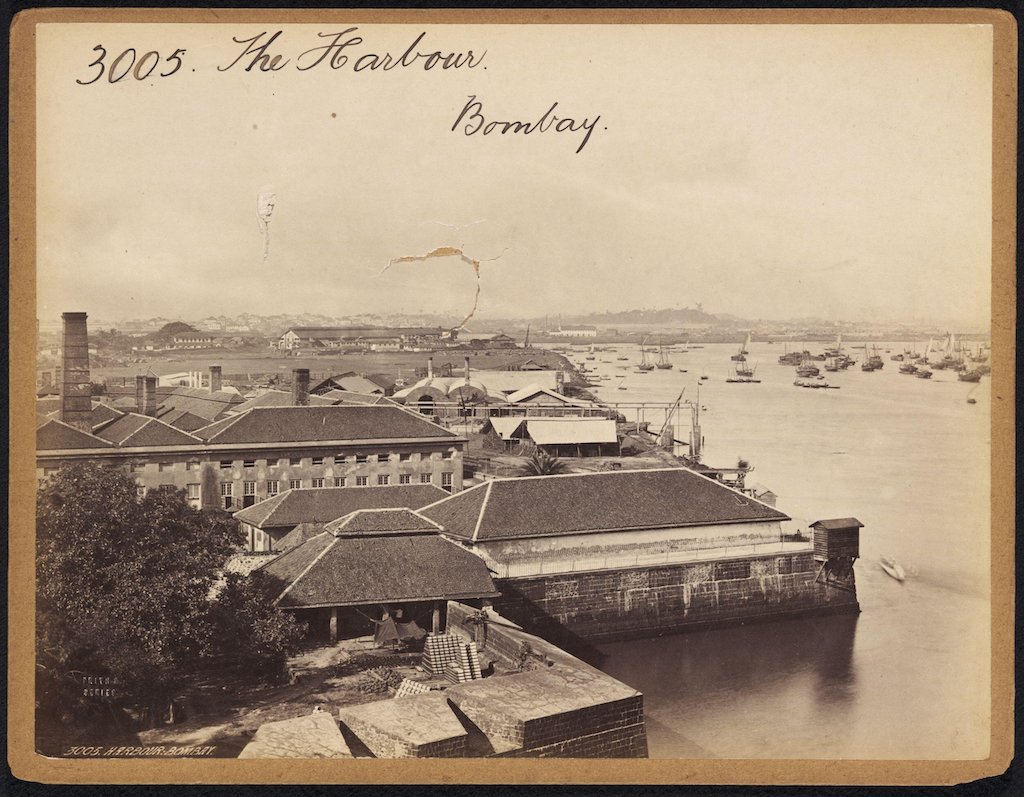

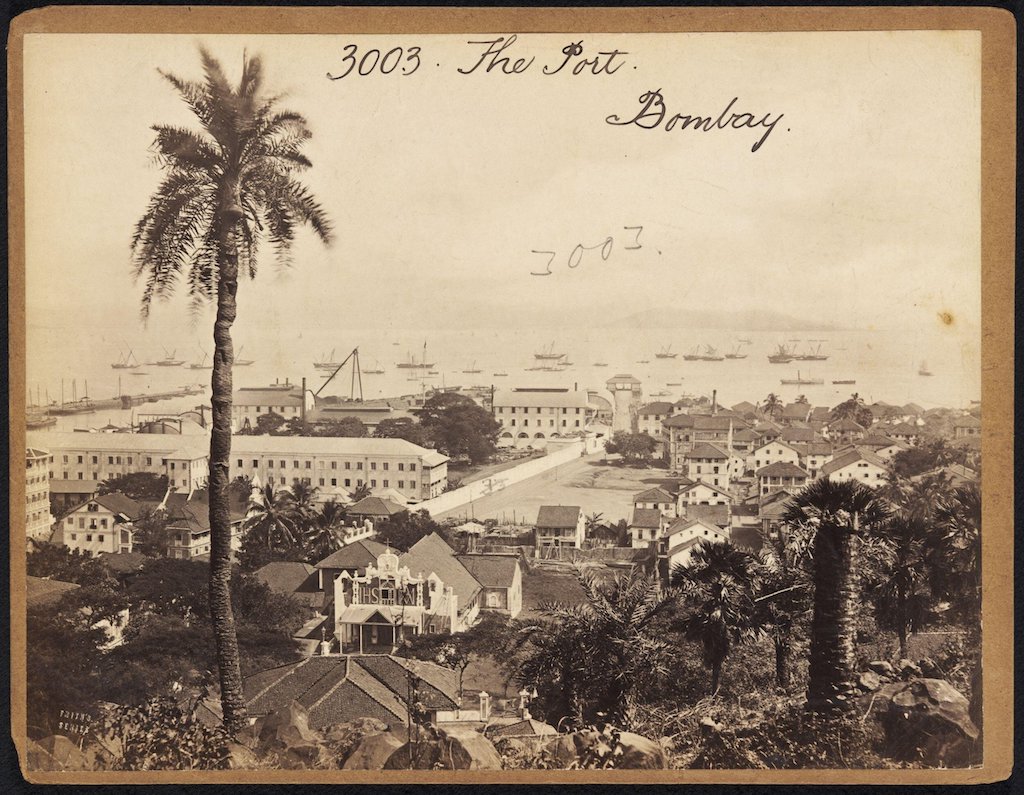

And it’s in Bombay where things really start going wrong.

Barbarity in Bombay

It’s not exactly clear what precise date the Elphinstone arrived in Bombay harbour, but a report on the 5th of February 1848 in the Fine Arts column of the London paper The Athenaeum reports on a report in the Bombay Times reporting on the arrival of “cultured slabs from Mosul, forwarded by Major Rawlinson to the Governor”.31

When Layard first read this report he was so confused by its garbled details that he didn’t know if the report in question was about his artefacts at all!32

It was the chain of command in the British Empire’s hierarchy that the Resident at Baghdad reported to the Governor at Bombay,33 so regardless of the fact that the cases of artefacts were addressed to the Trustees of the British Museum, Rawlinson had sent the artefacts to Bombay for the attention of “The Governor”34. The Governor of Bombay was one George Russell Clerk.35

On the Ephinstone’s arrival the cases that had been so carefully packed by Layard and repacked by Rawlinson were unloaded onto the dockside and unceremoniously opened by Clerk’s people.

Again, a note in The Athenaeum’s “Fine-Art Gossip” column helps to fill in the gaps. June 24th 1848’s column36 brought its readers’ attention to a Bombay Times article mentioning an exhibition of Layard’s Artefacts. And, it wasn’t just one or two small items that were on display; from the description given in the Bombay Times article quoted by The Athenaeum, it was loads of items. But for our purposes, here’s the interesting part: after listing off all sorts of items the Bombay Times article mentions,

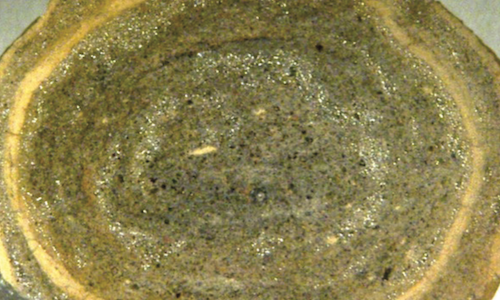

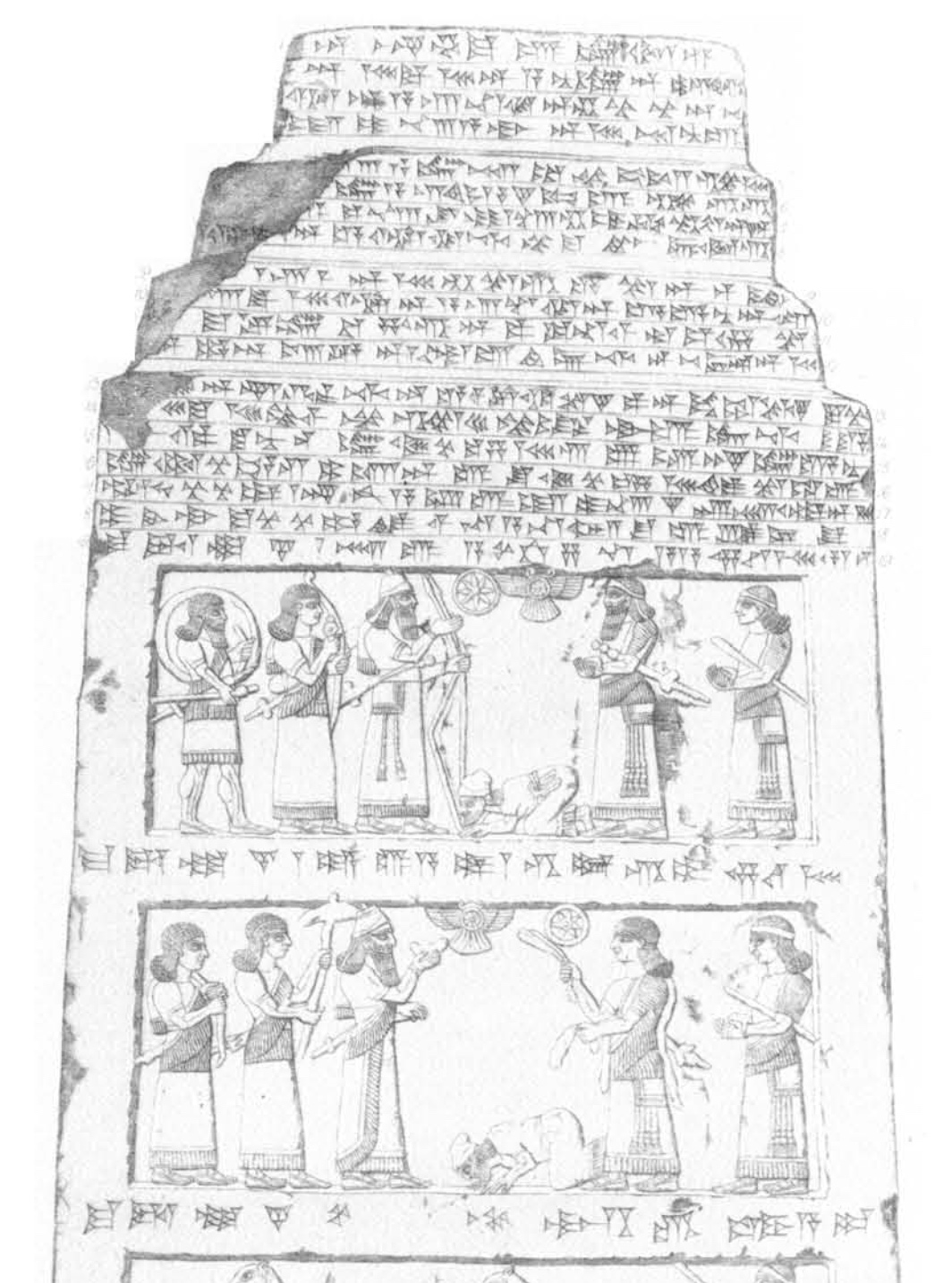

“The principal object of attention was a beautiful obelisk of black marble, six feet high, and in the most perfect state of preservation, – the polish unaffected by three thousand years of inhumation, and the lustre hardly gone”37 and then it goes into an accurate description of the Black Obelisk.

Now, if you think these objects were displayed in some temporary exhibition in a properly equipped museum, you’d be wrong. They were displayed in the dockyard.38

The person responsible for the artefacts’ display was one Dr. George Buist: a preacher, the Editor of the Bombay Times39, “the city’s leading scientist”40, a frequent contributor of scholarly articles to the Journal of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, and a Fellow of the prestigious Royal Society41. Not only did he exhibit the artefacts on the dockside, he lectured on the Obelisk at the monthly Meeting of the Bombay Royal Asiatic Society.42

Then, after not only exhibiting the obelisk at the dockside and lecturing on it, Dr Buist had the audacity to add yet further to the “unjustifiable liberties”43 he’d taken with Layard’s discoveries. Instead of shamefacedly and very carefully repacking the obelisk and other artefacts and sending them on their way, he arranged for a number of plaster casts of the obelisk to be taken. But, of course, this was fine because before doing so he gave “a personal pledge that no harm could result”44 from taking an unpublished artefact delicately inscribed in a writing system that had yet to be properly deciphered and covering it with Plaster of Paris, waiting for it to dry, and then ripping it off.

What a cretinous collection of colonialist clowns.

Thankfully, nothing did go wrong with the plaster casts. Sadly, some of the artefacts displayed at the dockside didn’t fare so well at the hands of those who came to look at the artefacts – many of them were stolen. A few of the items have been tracked down and retrieved or handed back in; so let’s go on a museum junky tangent…

More than fifty years after their discovery, in 1897, one Miss H. G. Wainwright “donated” to the British Museum a number of artefacts that she’d inherited from her father, William Wainwright, who’d been in Bombay at the time Layard’s artefacts were being exhibited in the dockyard.45 Most of the artefacts she donated are boxed up in the museum’s archives, but a couple of them are on display.

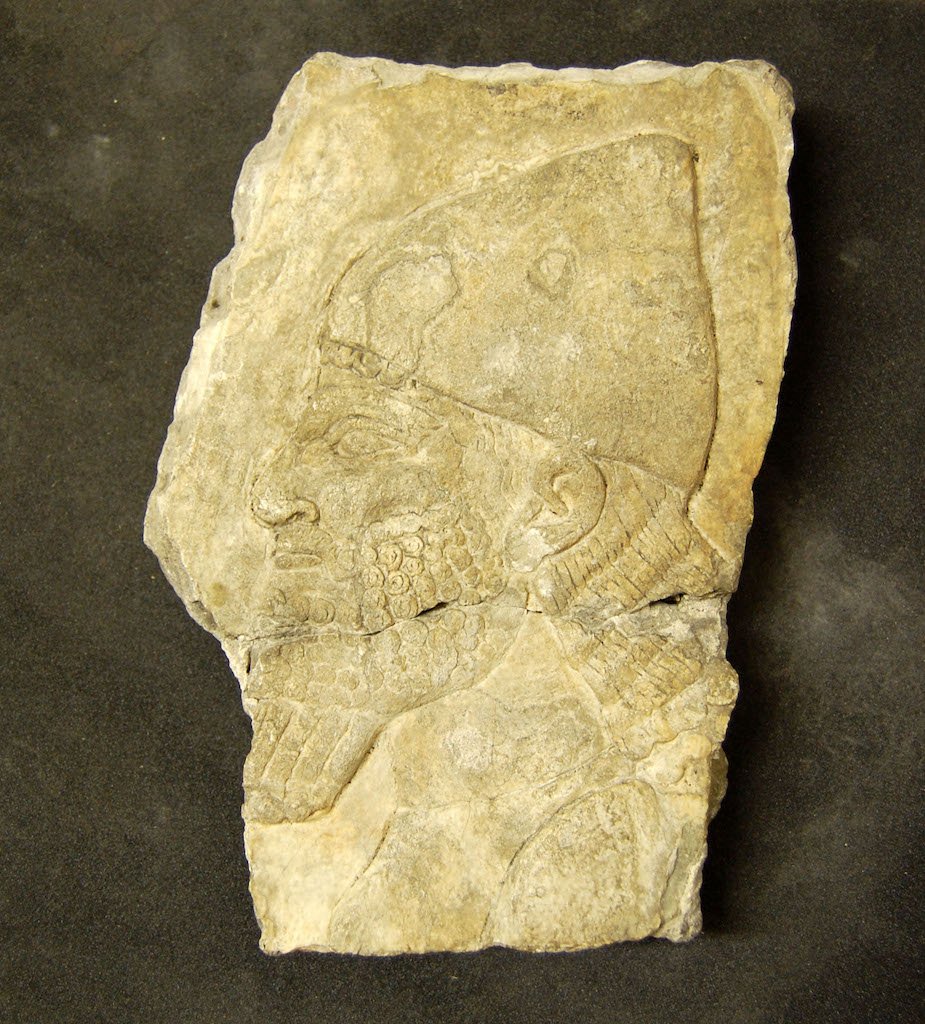

The first of these artefacts that you can go see for yourself is a cracked relief of some guy’s head46, on display in room 56, very close to the famous Flood Tablet:

I’ve not been able to find anything that explains why the relief is cracked, so I like to imagine it’s because William Wainwright couldn’t otherwise fit it under his jacket as he wandered away from the dockside where he robbed the artefacts, so he quietly karate chopped it behind the Black Obelisk before stuffing it under his jumper and sauntering off.

The second of the artefacts Wainwright pilfered is displayed in the Museum’s “Assyria: Nineveh” area near the end of room 9, directly below the well known Phoenician ship relief:47

It’s of an Assyrian male fishing in a pond. It’s quite cool to see it listed on Layard’s manifest in his book – it’s item 74.48 It’s a beautiful little fragment – for years I’ve enjoyed it every time I’ve walked through this gallery though I never knew the backstory to it.

Cyclones to Ceylon

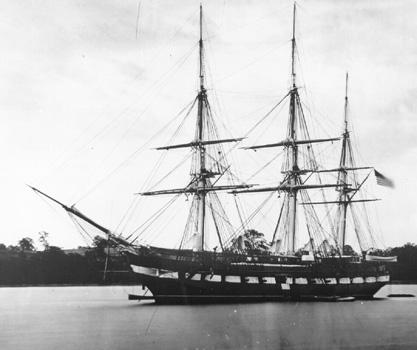

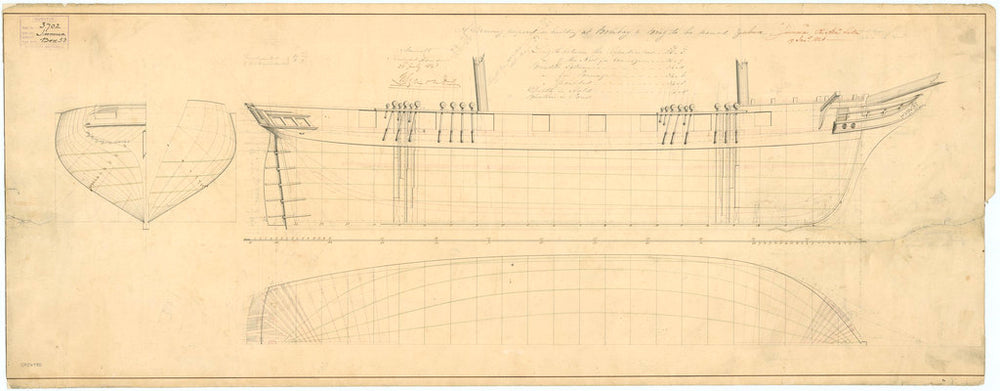

Anyway, all this time that the Obelisk had been on the dockside at Bombay harbour, workmen in the same harbour had been finishing off the construction of a new brig for the Royal Navy, the HMS Jumna;49 it was this ship that was to transport Layard’s artefacts to London.50

From Bombay, ships would sail to London by first sailing around the bottom of the Indian subcontinent and up the other side, picking up goods from port cities like Calcutta (now Kolkata). From there it would sail south down India’s eastern shore for Ceylon, modern Sri Lanka. Off the Sri Lankan coast the ships would pick up the trade winds that would blow them down past Madagascar, and around Africa’s southern tip at the Cape of Good Hope. From there the ship would sail north through the Atlantic around Western Africa, past Spain, eventually reaching Chatham Docks, just east of London in the Thames Estuary.

But, the HMS Jumna’s maiden voyage would not be so idyllic. In fact, the ship’s story begins and ends in disaster. We’ll get into its disastrous maiden voyage carrying the obelisk in a minute, but it’s worth knowing about the ships’ poignant end.

The Jumna had a 33 year long career. Its final voyage began in Hobart on the island of Tasmania – south of the Australian mainland. It had arrived there from Mauritius laden with sugar, but after unloading it wasn’t able to pick up any new cargo, so its sailors filled it with 60 tons of ballast –far too little for a ship of its size– and set off westward for the port of Fremantle on Australia’s western seaboard. It never made it. None of the sailors survived whatever the ship’s fate was, and though some wreckage was found on a beach near Fremantle it couldn’t be shown for sure that it came from the HMS Jumna. People who knew the ship theorised that the ship must have capsized in a squall and sank, but we’ll never know for sure.51 Whatever happened, it wasn’t a happy ending.

So, back in Bombay harbour at the beginning of the Jumna’s career… The ship was loaded up with 55 of Layard’s cases52 of discoveries – things had taken so long that by now there was a bit of a backlog of them on the Bombay dockside. The ship, under the direction of one Captain Lieutenant Rodney, set off for London on the 12th of April 1848.53 As planned, it headed south-east.

The first few days were uneventful. As it happened, 3 days into the voyage, on April 15th, Layard happened to be lecturing in London at the Royal Asiatic Society – he had no way of knowing that his artefacts had begun the last leg of their journey to the British Museum. He discussed the particulars of the dating of the various artefacts, with people in the audience disagreeing on just how old the artefacts were.54 Little did he know what was in store for the very artefacts he was busy chatting about.

The Jumna had sailed around the bottom of the Indian subcontinent and up the other side, arriving in the port city of Calcutta. The next day, the 22nd of April, after loading up more goods bound for London it set off again heading south for Ceylon.55

That evening, the Jumna encountered bad weather; such bad weather in fact that it got written up in an article in the 1850 Journal of the Asiatic Society.56 And, when we say bad weather, the Jumna managed to sail straight into the point where three57 cyclones collided, and it was stuck in that tempest for the best part of two days58 almost sinking to the bottom of the sea. Here’s how it played out.

At 3am on April 23rd, the gale force 5 cyclone with its thunder and lightning increased to a gale force 7 or 8. As the hours wore on it got worse and worse such that at 8:45am the next morning the storm was a gale force 10. It stayed at that level until 3pm when it dropped to a mild force 9 gale, until the ship sailed into the eye of the storm where it was all calm at 4pm. At 4:30pm they were back in a force 6 cyclone, and at 7pm they were back in force 10. From 8pm to midnight the storm was between a force 10 to 12, but was “said to be higher than the figures can express” – the storm was literally off the scale. This lasted for quite a few hours, and at 10:45am the next morning, according to the ship’s logs, the ship “broached to and went over and the mainmast was cut away to right her”.59

In non-sailor speak “broached to” means that as a result of being pushed from behind either by a massive wave or a particularly hellish gust of wind, the boat was flipped over, landing upside down. And, because this was in the days before boats were self-righting, the crew had to cut away the mast to get the ship the right way up again. Later in the day the storm finally calmed.60

This, it’s probably fair to say, is not really what you want happening to one of the most important archaeological finds ever.

What remained of the Jumna then limped through the water “under jurymasts” –that is, makeshift masts made out of bits of the ship– and after a few days it slunk into the port of Trincomalee in Ceylon, modern Sri-Lanka.61

The ship needed refitting, and this caused quite the delay.62 Thankfully, none of Layard’s artefacts had been lost – all was well.

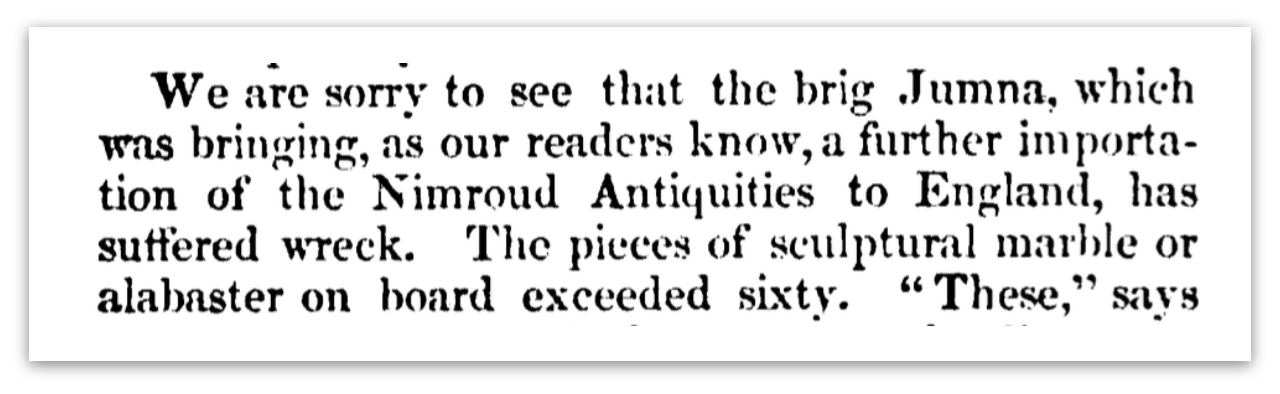

But this is not the news that reached Layard’s ears in London. On August 12th 1848, the Athenaum newspaper, Layard’s source of news about his precious artefacts, printed a summary of an article in the Bombay Times:

“We are sorry to see that the brig Jumna, which was bringing, as our readers know, a further importation of the Nimroud Antiquities to England, has suffered wreck. The pieces of sculptural marble or alabaster on board exceeded sixty.”63

It’s hard to imagine Layard reading that report and him not having a stroke.

First the artefacts suffered intellectual property theft in Baghdad. Then they were stuck in Basrah for the best part of a year. Then they were robbed in Bombay. And now they’re at the bottom of the ocean! Poor Layard – unknown to him he was an early victim of Fake News.

The final leg to London

It now being midsummer after spending a couple of months under repairs in Trincomalee, the Jumna set off for London on July 1st 1848.64 It picked up the trade winds, sailed past Madagascar and around the Cape of Good Hope, arriving on August 20th on the tiny southern-Atlantic island of St Helena.65 Five days later, on August 25th, the Jumna sailed past Ascension Island66, an even smaller rock sticking out of the ocean than St Helena is.

Six more weeks went by, and on October 3rd the Jumna lowered its anchor at Spithead just outside Portsmouth Harbour.67 Finally, 10 days later, on the 13th of October 184868 the HMS Jumna reached its final destination and sailed into Chatham Docks, east of London.69

Reporting on the event, the Athenaum wrote,

“The long-expected marbles from Nimroud, embarked on board the Jumna and which were reported to have been lost at sea, have, we are happy to say, at length arrived…”70

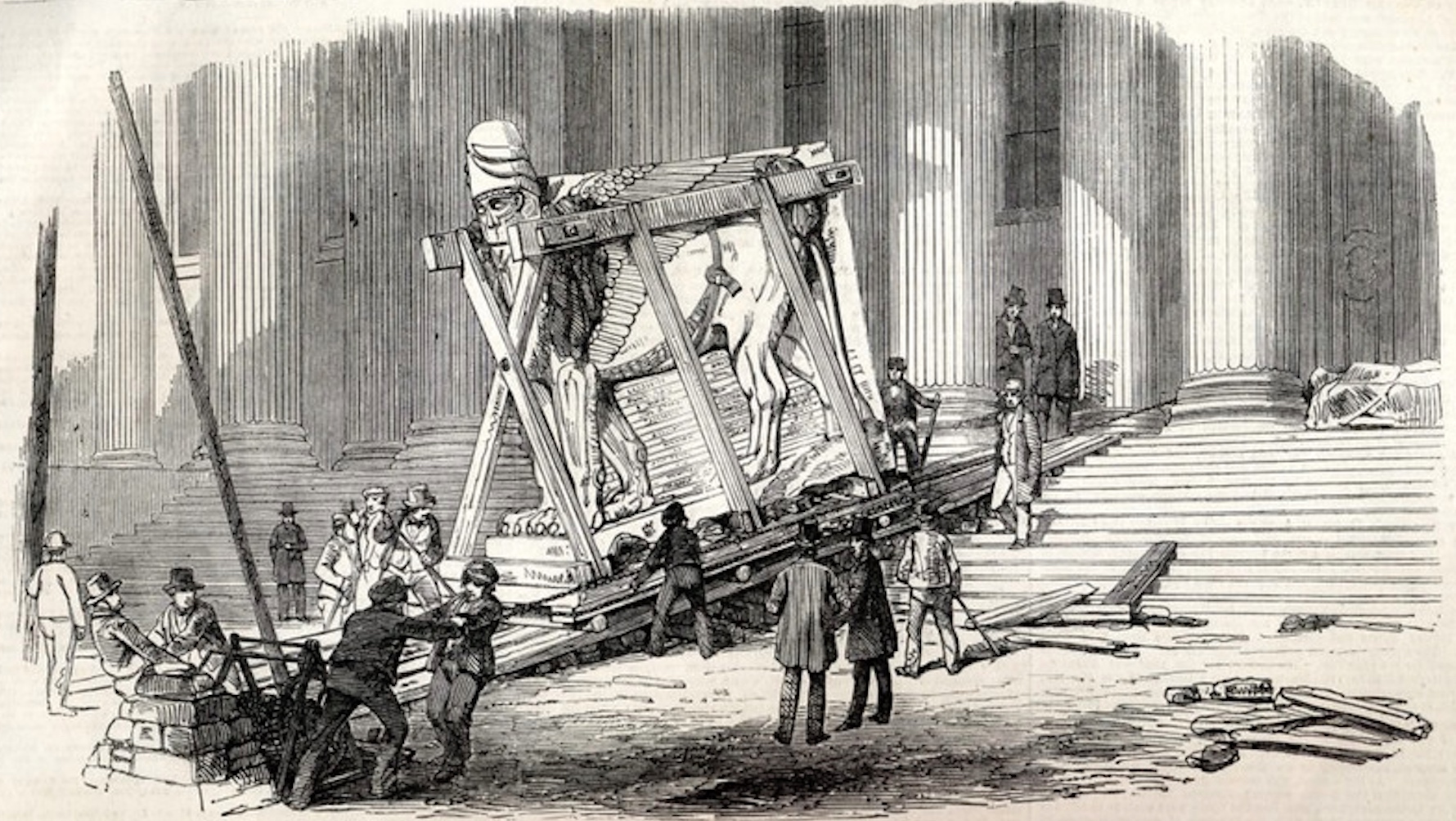

Normally, goods entering England would be inspected by customs officials on arrival at the docks. But for Layard’s 50 cases, special provision was made. They were were transported “under seals” from the docks to the British Museum, accompanied by customs staff. On arrival at the museum the crates were unsealed in the presence of the customs staff, the museum trustees, and of course, Austen Henry Layard.71

Layard’s initial relief at receiving his artefacts back from the dead very quickly turned to outrage. To quote Gadd,

“…the state of the contents of the thirty boxes of small objects was such as to evoke the strongest expressions of indignation. Privately he used much more emphatic language…”72

The artefacts had been terribly packed; any order Layard had put them in was gone. Some of the artefacts had been smashed. Some of the smaller artefacts had been stolen.

Furious with what they’d found, the Trustees of the Museum wrote off to the Governor at Bombay asking what on earth had happened. In reply they received a report mentioning some of the events we saw took place in Bombay.73 I imagine that things weren’t helped when the ship “went over” in the cyclones either, so the disorganised mess wasn’t completely the fault of Dr Buist’s men in Bombay, but it was certainly almost entirely their fault.

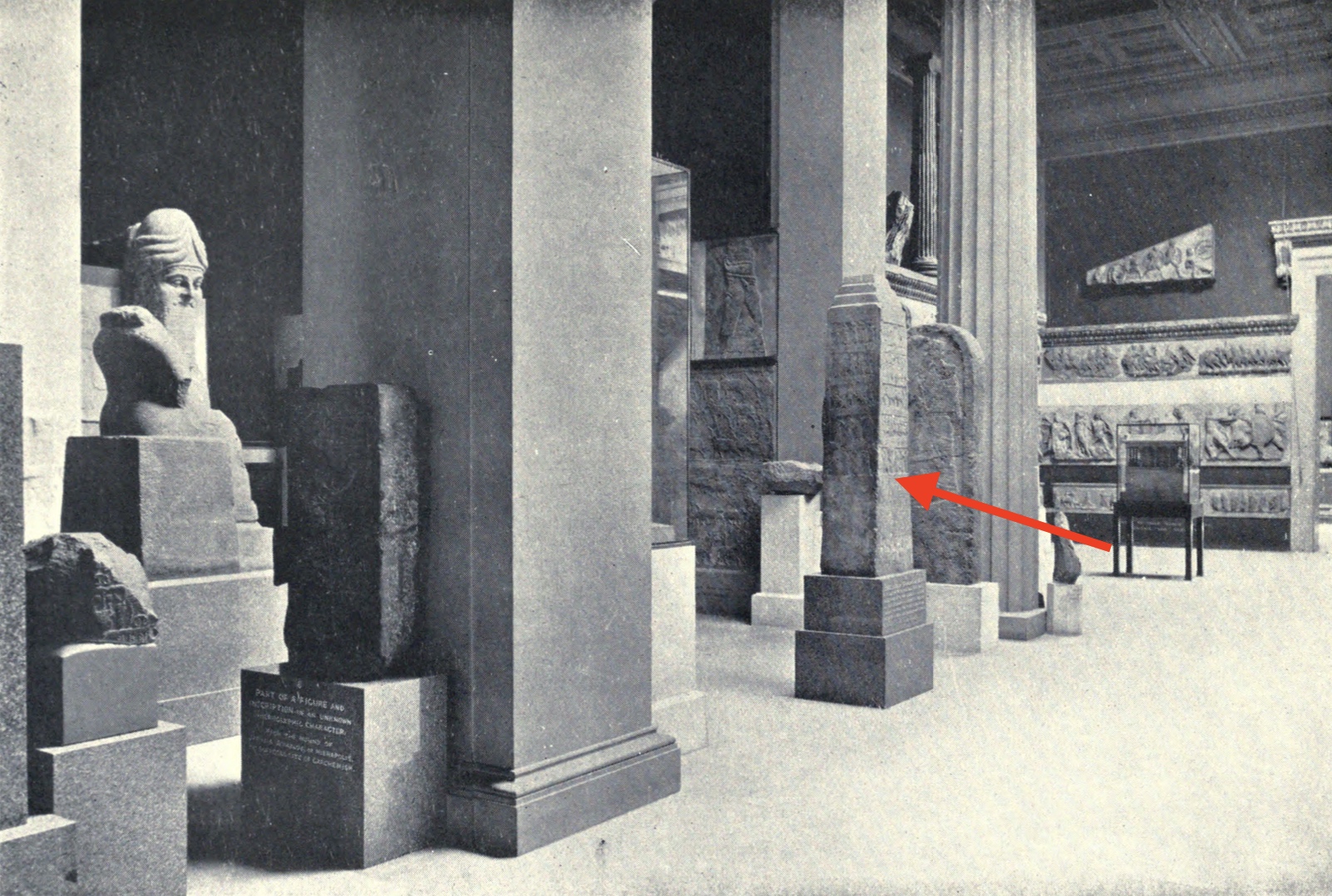

And so, the customs officials went back to their docks. At last Layard’s artefacts were brought into the museum. They were put on display in the Nimroud Saloon, with pride of place going to the Black Obelisk.74 Almost two years after its initial discovery, and after many adventures, the artefact could finally rest.

And, it’s bizarre to think about it now, but the obelisk was on display for more than three years before scholars worked out that the “bearded figure” “in the attitude of awe”75 was none other than the Israelite King Jehu. More about that in the next Beyond Apologetics video.

Featured image

- My photo of the Black Obelisk superimposed on Layard’s map of Nimrud (public domain) and Raden Saleh’s “Ships on a Stormy Sea” (public domain)

Further reading

- Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production - The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III

- Cyril John Gadd, The Stones of Assyria (London, 1936)

Footnotes

-

George Rawlinson, A Memoir of Major-General Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson (London, 1898), 151. ↩

-

Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and its Remains (London: 1849), 16-17. ↩

-

Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and its Remains (London: 1849), 19 & 21. ↩

-

“On the 8th of November [1845], having secretly procured a few tools, and engaged a mason at the moment of my departure, and carrying with me a variety of guns, spears, and other formidable weapons, I declared that I was going to hunt wild boars in a neighbouring village, and floated down the Tigris on a small raft constructed for my journey. I was accompanied by Mr. Ross, a British merchant of Mosul, my Cawass, and a servant. At this time of the year more than five hours are required to descend the Tigris, from Mosul to Nimroud.” Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and its Remains (London: 1849), 21-22. ↩

-

“I continued to employ a few men to open trenches by way of experiment, and was not long in discovering other sculptures…” Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and its Remains (London: 1849), 46. ↩

-

“In the centre of the mound we uncovered part of a pair of gigantic winged bulls, the head and half the wings of which had been destroyed. Their length was fourteen feet, and their height must have been originally the same.’ Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and its Remains (London: 1849), 46. ↩

-

“During the next campaign in 1975, east of this relief two Lamassu-bulls of Shalmaneser III were found; the form an entrance to a building lying more to the west. These sculptures were known from Layard’s time and were called “The Centre Bulls”, but their exact position was unknown till our excavations.” A. Mierzejewski & R. Sobolewski, “Polish Excavations at Nimrud/Kalh 1974-1976: Some preliminary remarks on the new discovered neo-assyrian constructions and reliefs,” Sumer 36 (1980), 152-153. ↩

-

“The excavations were recommenced, on a large scale, by the 1st of November.” Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and its Remains (London: 1849), 332. ↩

-

“My working parties were distributed over the mound – … [including] in the centre of the mound near the gigantic bulls (* at i and j, plan 1)” Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and its Remains (London: 1849), 332. ↩

-

Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and its Remains (London: 1849), 344-347. ↩

-

Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and its Remains (London: 1849), 344-347. ↩

-

“Trenches were also dug in two other areas on the Akropolis. First of all some digging was done in what is known as the centre palace of Tiglath-pileser III on the square where it was believed Layard had found the black obelisk of Shalmaneser III. Here, however, work was not prolonged because it was found that what was left of the building was in a ruinous and badly damaged condition. Indeed to recover more of the old plan and the alignment of the street would have been a major operation. Our efforts were needed elsewhere.” Max Edgar Lucien Mallowan, “The Excavations at Nimrud (Kalhu), 1952,” Iraq 15.1 (1953): 5. ↩

-

Correspondence in Gordon Waterfield, Layard of Nineveh (London, 1963), 168. ↩

-

Correspondence in Gordon Waterfield, Layard of Nineveh (London, 1963), 168. ↩

-

Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and its Remains (London: 1849), 348. For the sketches themselves see Austen Henry Layard, The Monuments of Nineveh, from drawings made on the spot (London, 1849), Pl. 53-56. ↩

-

Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and its Remains (London: 1849), 348. ↩

-

Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and its Remains (London: 1849), 348. ↩

-

Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and its Remains (London: 1849), 372. ↩

-

Cyril John Gadd, The Stones of Assyria (London, 1936), 41-42. ↩

-

George Rawlinson, Memoir of Sir Henry Rawlinson (1898), 153-154. ↩

-

From the archives of the Royal Asiatic Society: ‘Addressed to “E Norris [as above] Baghdad 27th Jany 1847 My dear Sir” Marked “Confidential” The recent extraordinary discoveries by Layard at Nimrud have caused him to set aside his work on the Persian vocabulary and set about Assyrian in earnest. Description of a black marble obelisk, but asks Norris not to publish this for fear of upsetting Layard and the Trustees of the British Museum. Gives some of the results of his Assyrian researches including the identification of a genealogical series of the four primeval kings of Assyria but concludes that he was wrong in his last letter in stating that there were two king Nebuchadnezzars [Norris adds the note “see letter R”.] Comments on the “extraordinary laxity of the Assyrian character”. He can read much of the script phonetically, but can get no further because the materials for comparison are too scanty. He is not prepared to publish his key yet unless “Dr Hincks or the Savans of France & Germany are prepared to come forward” as “I should like to penetrate a little deeper into the primitive Assyrian records before I give up the keys of the enquiry.” He will also need to consult Layard and the Commissioners of the British Museum before publishing any results derived from a study of the inscriptions on the items which are their property. Encloses a letter to the Commissioners for that purpose. [Letter P in III/04]’. See https://royalasiaticsociety.org/list-of-the-ras-collections-of-sir-henry-creswicke-rawlinson-bart-1810-1895/ ↩

-

Cyril John Gadd, The Stones of Assyria (London, 1936), 41. ↩

-

Cyril John Gadd, The Stones of Assyria (London, 1936), 42. ↩

-

Cyril John Gadd, The Stones of Assyria (London, 1936), 42. ↩

-

Cyril John Gadd, The Stones of Assyria (London, 1936), 43. ↩

-

Gordon Waterfield, Layard of Nineveh (London, 1963), 179-180. ↩

-

“…when Rawlinson was at Basrah in December 1847 he had the satisfaction of seeing, one day, the Company’s sloop-of-war Clive arrive at the port, and he found that the commander, in accordance with his instructions, was prepared to take on board such antiquities as he had the capacity to carry, but he was to take them only as far as Bushire, where they would be trans-shipped to the Elphinstone and by her carried to Bombay. Unfortunately these sloops were only small craft and it was found that the Clive’s utmost capacity was twenty cases, the Black Obelisk… and all the portable boxes of small objects; these were accordingly stowed aboard in the driest and most sheltered positions” Cyril John Gadd, The Stones of Assyria (London, 1936), 42. ↩

-

Cyril John Gadd, The Stones of Assyria (London, 1936), 44. ↩

-

‘Persian Gulf Captain Lowe’s proceedings during his late tour of the Persian and Arabian Coasts. Vol: 2’, British Library: India Office Records and Private Papers, IOR/F/4/2260/114569, in Qatar Digital Library https://www.qdl.qa/archive/81055/vdc_100098593048.0x000001 (pdf page 8) [accessed 30 September 2022] ↩

-

“In this year the ‘ Elphinstone’ brought from the Persian Gulf, some of the sculptures collected by Mr. Layard and Major Rawlinson for the British Museum…” Charles Rathbone Low, History of the Indian Navy (1613-1863) Volume 2 (London, 1877), 201. ↩

-

“Fine Arts,” The Athenaeum, February 5, 1848, pp. 146-147. ↩

-

“The first quarter of 1848 passed away thus in rather waning hopes at Basrah, while at home there came reports of an arrival of antiquities from Nimrud at Bombay, namely, those taken on board the Clive. The accounts of them furnished by the local press were so garbled that Layard at first did not think it could be his discoveries at all, but later he received news from Rawlinson that some of his cases had indeed been sent.” Cyril John Gadd, The Stones of Assyria (London, 1936), 44. ↩

-

“1552. ‘Does not the Government of Bombay also correspond with the Resident at Bagdad?’ ‘Yes.’ 1553. ‘And which Resident at Bagdad reports to the Government of Bombay the despatches which he writes to the English Ministers at Teheran and at Constantinople?’ ‘He does.’” Minutes of Evidence taken before the Select Committee, Examination of Sir George Russell Clerk K. C. B. 24th May 1852, Session 4 November 1852–20 August 1853, Reports from Committees: Thirty-Two Volumes, Vol. 30., 145. https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Parliamentary_Papers/1ZcSAAAAYAAJ ↩

-

“Fine Arts,” The Athenaeum, February 5, 1848, pp. 146. ↩

-

“Clerk, Sir George Russell (1800-1889)… He was Lieutenant-Governor of the N. W. P., June to Dec. 1843: Provisional Member of the Supreme Council, 1844: twice Governor of Bombay, from 1847 to 1848: K. C. B.: and from 1860-2.” C. E. Buckland, Dictionary of Indian Biography (London: 1906), 84. https://archive.org/details/dictionaryofindi00buckuoft ↩

-

“The Bombay Times gives some account of a portion of the last packages of Nimroud marbles despatched from thence for England, on board the Jumna. The articles there exhibited were “a fragment – the feet and ancles [sic] – of a gigantic ox, and the head of a king in relief, in very fine preservation, both cut in gypsum. Besides these, was a basket full of vases, lamps, and other utensils, mostly in terra cotta, and of very elegant patterns. One small urn was of fine white alabaster. The principal object of attention was a beautiful obelisk of black marble, six feet high, and in the most perfect state of preservation, – the polish unaffected by three thousand years of inhumation, and the lustre hardly gone. This marble is much more perfect than any of the gypsums with which it is contemporaneous. About one-third of it is covered all round with inscriptions in cuneiform characters; the other two-thirds are decorated with sculptures in compartments. There are five compartments on each side, – twenty, consequently, in all. They are sunk about one-forth of an inch, and occupied by figures of men, horses, camels, tigers, deer, and monkeys, in relief. The whole seems to represent a procession bringing gifts to the king, – who, along with his courtiers, is represented at the top of the stone.” Castings in plaster of Paris, for the study of the local antiquaries, were taken from the obelisk while at Bombay.” “Fine-art gossip”, The Athenaeum, No. 1078 (Saturday June 24th, 1848), 635. ↩

-

“Fine-art gossip”, The Athenaeum, No. 1078 (Saturday June 24th, 1848), p. 635. ↩

-

“…certain of the cases had, in fact, been opened at Bombay. It was stated that the contents of five only had been exhibited to the public in the Dockyard, and that this had occurred only in the course of their being re-packed…” Cyril John Gadd, The Stones of Assyria (London, 1936), 50. ↩

-

Charles Rathbone Low, History of the Indian Navy (1613-1863) Volume 2 (London, 1877), 203. ↩

-

Julian Reade, “Nineteenth-Century Nimrud: Motivation, Orientation, Conservation,” in New Light on Nimrud: Proceedings of the Nimrud Conference 11th-13th March 2002, eds. J.E. Curtis, H. McCall, D. Collon and L. al-Gailani Werr (British Institute for the Study of Iraq, 2008), 16. ↩

-

https://catalogues.royalsociety.org/CalmView/Record.aspx?src=CalmView.Catalog&id=EC%2f1846%2f07 ↩

-

‘The Bombay Monthly Times. From 20th May to 18th June, 1848 contained a report on the monthly Meeting of the Bombay Royal Asiatic Society of 11 May 1848, at which Dr. Buist gave a paper on The Nimroud Obelisk of which plaister casts had been made. … In the meanwhile on the Bombay docks “it was the most anxious wish of the late Governor –and we believe of every member of the Council– that [the antiquities] should be exhibited to the public and casts in plaister taken of them. After some six weeks’ delay a single obelisk with some fragments were shown: the rest were at once sent on board as soon as they could be returned – the public saw nothing of them whatever.”’ Geoffrey Turner, The British Museum’s Excavations at Nineveh, 1846-1855 (Brill, 2020), 78. ↩

-

Cyril John Gadd, The Stones of Assyria (London, 1936), 49. ↩

-

Cyril John Gadd, The Stones of Assyria (London, 1936), 50. ↩

-

“Among…[those] who participated in the Bombay incident and maltreated the contents of Layard’s packing cases there was, it is proposed, one William Wainwright who appropriated the eight relief fragments his daughter H. G. Wainwright handed back to the British Museum in 1897.” Geoffrey Turner, The British Museum’s Excavations at Nineveh, 1846-1855 (Brill, 2020), 79. See https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG63132 ↩

-

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1897-1008-5 ↩

-

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/W_1897-1008-1 ↩

-

Austen Henry Layard, Nineveh and its Remains (London: 1849), 399. ↩

-

David Lyon and Rif Winfield, The Sail and Steam Navy List: All the Ships of the Royal Navy, 1815-1889 (Chatham, 2004), 128. ↩

-

“… it was decided that they should be forwarded to England in one of the new sailing-ships then being built for the Royal Navy at Bombay. For this purpose H. M. brig Jumna was selected: she took on board all fifty-five cases which had reached Bombay, and sailed on April 12th, 1848.” Cyril John Gadd, The Stones of Assyria (London, 1936), 49. ↩

-

“The Lost Brig Jumna,” The Mercury (Hobart, Tasmania), Saturday 22 April 1882, 2. ↩

-

Cyril John Gadd, The Stones of Assyria (London, 1936), 49. ↩

-

Charles Rathbone Low, History of the Indian Navy (1613-1863) Volume 2 (London, 1877), 200. ↩

-

“Societies”, The Athenaeum, No. 1095 (Saturday May 20th, 1848), 510-511. ↩

-

“Shipping Intelligence”, Liverpool Albion (Monday April 24th, 1848), 7. ↩

-

Henry Piddington, “A Nineteenth Memoir on the Law of Storms in the Indian and China Seas, being the Cyclones of the Sir Howard Douglas and of H. M. Brig Jumna in the Southern Indian Ocean. January to April, 1848,” Journal of the Asiatic Society 50 (1850), 349-389. ↩

-

“…the brig Jumna, under the command of Lieut. RODNEY, from Bombay to England, on the 23rd April, at 3 A.M. … was between or near the tracks of two larger Cyclones, travelling down to the S.S.E., while she herself was on the verge and within the influence of a much smaller one…” Henry Piddington, The Sailor’s Horn-Book for the Law of Storms (London, 1860), 209-210. Also, “…the Jumna was bringing down with her another small Cyclone, and… we can easily understand that at the point where the two [large cyclones] approximated and combined, the fury of the tempest might be much augmented and the track subject to some variation.” Henry Piddington, “A Nineteenth Memoir on the Law of Storms in the Indian and China Seas, being the Cyclones of the Sir Howard Douglas and of H. M. Brig Jumna in the Southern Indian Ocean. January to April, 1848,” Journal of the Asiatic Society 50 (1850), 381. ↩

-

Henry Piddington, “A Nineteenth Memoir on the Law of Storms in the Indian and China Seas, being the Cyclones of the Sir Howard Douglas and of H. M. Brig Jumna in the Southern Indian Ocean. January to April, 1848,” Journal of the Asiatic Society 50 (1850), 380. ↩

-

“When the three Cyclones met, the fury of the wind became irresistible, and H. M. Ship was upset, but fortunately righted, by cutting away her mainmast.” Henry Piddington, The Sailor’s Horn-Book for the Law of Storms (London, 1860), 210. ↩

-

Henry Piddington, “A Nineteenth Memoir on the Law of Storms in the Indian and China Seas, being the Cyclones of the Sir Howard Douglas and of H. M. Brig Jumna in the Southern Indian Ocean. January to April, 1848,” Journal of the Asiatic Society 50 (1850), 358-359. The article also provides extracts from the ship’s logs giving the ship’s coordinates at various points in the storm: [23rd April 0300 – 8.59 S, 85.34 E; 23rd April 1200 – 10.28 S, 85.0 E; 23rd April 1600 – 11.08 S, 85.0 E; 24th April 1045 – 11.31 S, 84.54 E; 24th April 1200 – 10.14 S, 85.50 E] ↩

-

“On the 23rd she was caught in a great storm, dismasted, and in considerable danger of floundering, but succeeded at last in weathering the tempest, and making Trincomalee in Ceylon, where she was ordered to refit.” Cyril John Gadd, The Stones of Assyria (London, 1936), 49. ↩

-

“…and making Trincomalee in Ceylon, where she was ordered to refit. After much delay occasioned by this necessity she set sail again…” Cyril John Gadd, The Stones of Assyria (London, 1936), 49. ↩

-

“Fine-art gossip”, The Athenaeum, No. 1085 (Saturday August 12th, 1848), p. 810. ↩

-

“The new 16-gun brig Jumna, built at Bombay, arrived at Spithead on Wednesday, from Trincomalee, into which port she was driven in May last, much damaged, by a hurricane or monsoon. We hear she has brought home some of the late crew of the Cruiser, 16, found defective. She sailed for Chatham on Thursday morning to be paid off, and fitted for permanent commission. The Jumna sailed from Trincomalee on the 1st of July, on which day the Inflexible left for China. The Jumna arrived at St. Helena, August 20, and Ascension on the 25th.” “Portsmouth Herald”, The Hampshire Advertiser (Saturday October 7th, 1848), 8. ↩

-

“Portsmouth Herald”, The Hampshire Advertiser (Saturday October 7th, 1848), 8. ↩

-

“Portsmouth Herald”, The Hampshire Advertiser (Saturday October 7th, 1848), 8. ↩

-

“The Jumna, 16, Acting Commander M. Rodney, anchored at Spithead, on Tuesday evening from Bombay. She had a most boisterous passage. She has ben ordered to Chatham to be paid off, and was to have left last evening.” “The Navy,” London Evening Standard (Thursday Oct 5th, 1848), 8. ↩

-

Holger Hoock, “The British State and the Anglo-French Wars Over Antiquities, 1798-1858,” The Historical Journal 50.1 (2007), 67, n. 85. ↩

-

“The new brig Jumna, 16, from Bombay, is paid off at Chatham.” The Hampshire Advertiser (Saturday October 14th, 1848), 8. ↩

-

“Fine-art gossip”, The Athenaeum, No. 1095 (Saturday October 21st, 1848), p. 1057. ↩

-

“The packages, fifty in number, were permitted by the authorities at Sheerness to be at once sent up to London under seals, to undergo the Custom-house examination in presence of the authorities of the Museum, with a view to avoiding the risks attendant on the disturbance of articles of their valuable character and fragile nature.” “Fine-art gossip”, The Athenaeum, No. 1095 (Saturday October 21st, 1848), 1057. ↩

-

Cyril John Gadd, The Stones of Assyria (London, 1936), 48. ↩

-

“A letter was written to the Government of Bombay and it was discovered that the cases, while lying on the wharf at Bombay, had been opened by members of the British community.” Gordon Waterfield, Layard of Nineveh (London, 1963), 188. ↩

-

Synopsis of the Contents of the British Museum, 55th ed (British Museum, 1850), 112. ↩

-

“Fine-art gossip”, The Athenaeum, No. 1099 (Saturday November 18th, 1848), 1152. ↩