The Tel Dan Stele: Beyond Apologetics

NB: This post is available as a two-part youtube video.

The Tel Dan stele is a great example of the sort of archaeological discovery that apologists use to “prove the Bible true”. Sure, it mentions the “House of David”, and from an apologetics point of view, that’s pretty cool, but staying at that level can feel pretty shallow. When we dig deeper, the inscription highlights aspects of the biblical text that we might otherwise miss; aspects that force us to engage with the biblical text in more sophisticated ways than we otherwise might. And that’s way more interesting and useful than apologetic chest beating.

In this post we’re going to…

- …have a brief look at the way people were thinking about the Bible in the lead up to the stele’s discovery

- …look at how the Tel Dan stele was found, dated, and read

- …look at how the relevant scholars figured out who it mentions - and it’s more than just the House of David

- …see how the events related in the inscription line up or not with the way they’re recorded in the biblical text

- …think a little about what this means for the way we read and think about the historical books of the Bible

Minimalism

For most of the 20th century, archaeologists working in the Middle East dug with a spade in one hand and a bible in the other. These were the days of “Biblical Archaeology”, when “archaeology proved the Bible true”.

But, in the late 80’s things got considerably more complicated. Due to new discoveries and more modern methods, interpretations of previous discoveries were revised, old conclusions were shown to be incorrect, and confidence in a face-value, literal reading of the “historical” books of the Bible really dropped off.

At the extreme end of this development were a group of scholars who came to be labelled “minimalists”, for their shared view that there’s precious little in the “historical” books that’s historically accurate. In their eyes the historical value of the biblical texts was… minimal.

Here’s an example of the sort of thing that was being written about such central characters as Saul and David in the early 1990s:

…the narratives of Saul and David… serve no evident purpose at this point in the history of the kingdoms of Palestine. Who would need persuading of what by such fictions? 1

David, in the eyes of the minimalists, was a “fiction”. Elsewhere in the same book we come across this:

Whoever is living in the Palestinian highlands around 1000 BCE, they do not think, look or act like the people the biblical writers have put there. They are literary creations.2

Around 1000 BCE? He’s talking about the time of David.

So, David was thought of as a fiction; a literary creation.

There are similar quotes from other “minimalist” scholars we could have used, but the one we just looked at is important because of the timing. That book, by Professor of Biblical Studies at Sheffield, Philip Davies was published in 1992, just one year before the discovery of the Tel Dan stele. His timing was terrible…

Discovery of the 1st section

Site background

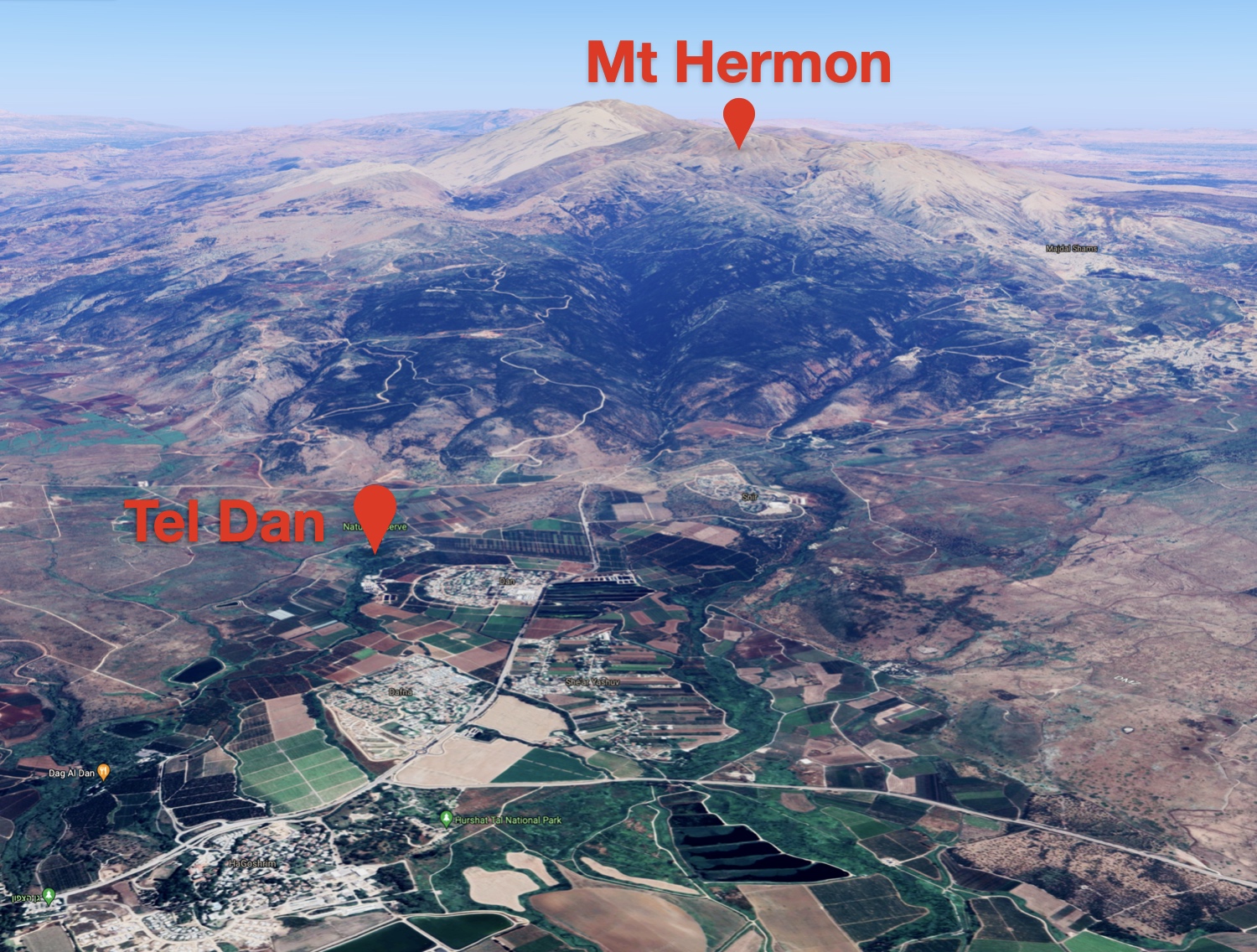

In the far north of the modern state of Israel, at the foot of Mt Hermon and only a few meters from the border with Lebanon, lie the remains of the ancient city of Dan - the site known today as Tel Dan.

Being one of the sources of the river Jordan, it’s a beautiful, green site and a welcome relief from the summer heat for tourists visiting the Holy Land.

Excavations began at Tel Dan in 1963, and even before the stele was discovered the site was famous for the discovery of what’s known as “Abraham’s Gate” –a well preserved Middle Bronze mudbrick gate– and the “High Place”, said to be the altar built by Jeroboam.

But it was in 1993 that the site’s most significant discovery would take place.

How the 1st section was discovered

(Sequence of events reconstructed from various sources3)

In 1993, the site was being excavated by Director of the Nelson Glueck School of Biblical Archaeology at Hebrew Union College, Avraham Biran.

Outside of excavation season, Biran drove up to the site from Jerusalem to show a visitor around the site. His site surveyor, Gila Cook, hitched a ride as she had some surveying work she wanted to finish at the site.

After some time the tour of the site was over and Biran called over to Cook to pack up her stuff - it was time for the long drive home.

Cook’s surveying equipment was bulky so on the way back to the car she set some of it down to rearrange it, so she could carry it a little easier. As she bent down to pick it up again she noticed that the light had fallen on a particular stone sticking up out of a newly excavated wall and on it she could see what looked like an inscription.

She called Biran over, they freed the slab, and they could make out the letters of an inscription as clear as day.

Initial publication

As many scholars have noted, Biran was quick to get the inscription published, something he did with Joseph Naveh, a Professor of West Semitic Epigraphy and Palaeography at the Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

When their article entitled “An Aramaic Stele Fragment from Tel Dan” was published in the Israel Exploration Journal, it became front page news. Like, New York Times front page news (Aug 6th 1993).

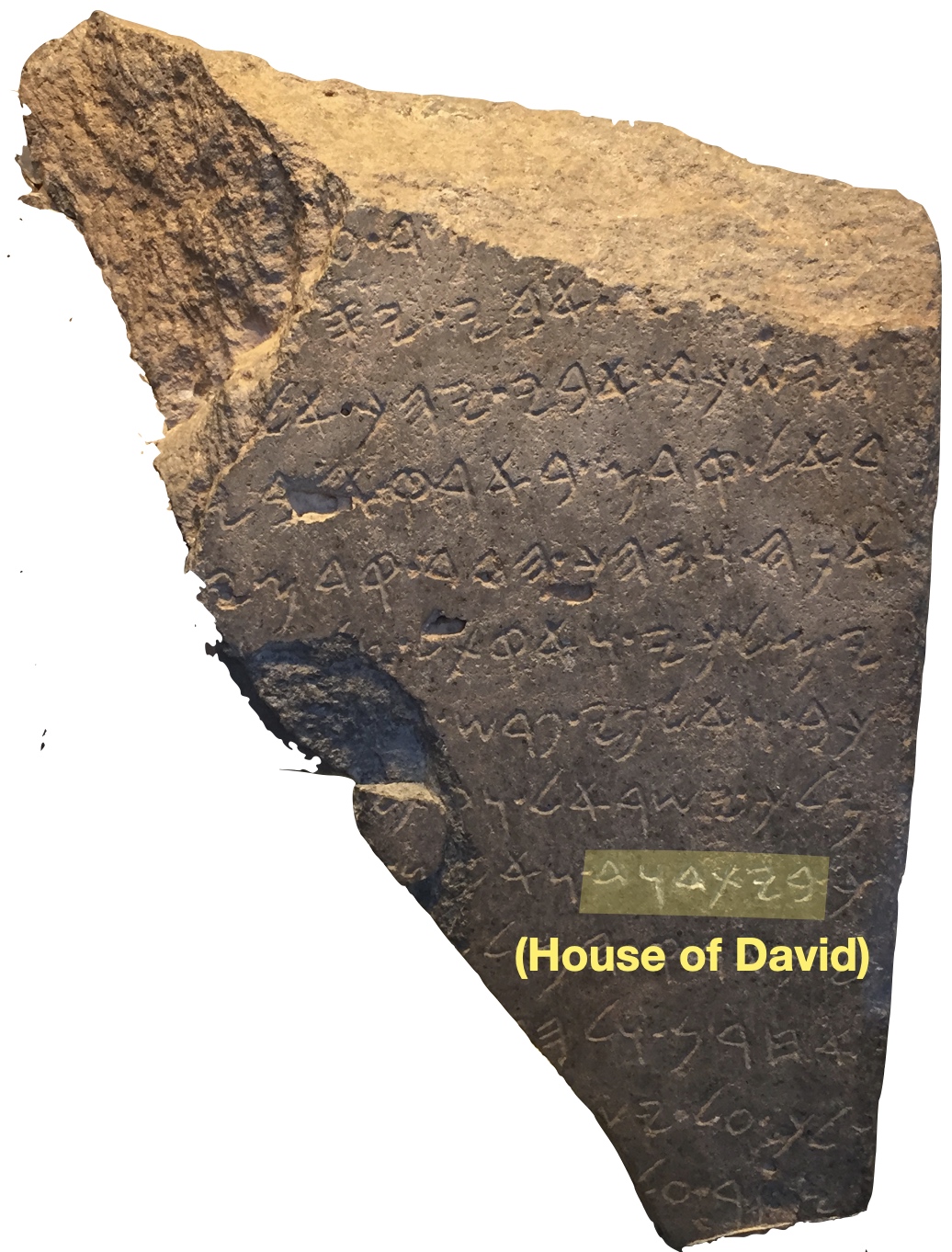

The reason for the global interest was because of what was found on the 9th line of the inscription. According to Biran and Naveh it read:

And [I] slew [… the kin-]g of the House of David.4

This was, to understate things, a massive deal. This was earth shaking stuff. The House of David.

The vast majority of scholars accepted the obvious. As Professor of Jewish Studies at the University of Georgia, Baruch Halpern wrote a couple of years later:

The Tel Dan inscription unmistakably indicates the existence of a dynasty in the ninth century B.C.E. that traced its origin to David.5

After many years of searching by Biblical Archaeologists, finally, David had been found.

Apologetics

As you can imagine, this is the stuff Christian apologists’ dreams are made of. In an age where archaeological “proof” of the biblical narratives is cited by many Christians as one of the foundations for their belief, tangible evidence of the existence of one of the great heroes of the bible is a big deal.

It’s worth stating at this point that apologists do tend to run way too far with discoveries like the Tel Dan stele. As Halpern pointed out, mention of the “House of David” actually isn’t evidence for anything other than “a dynasty in the ninth century B.C.E. that traced its origin to David”.

The stele isn’t evidence that David penned psalms, mourned Absalom, or killed Goliath. It isn’t evidence of any of the events in the life of the biblical David; it’s just evidence of a dynasty named after him. And it’s worth keeping a cool head about that – apologists shouldn’t overplay their hand.

If, one day, archaeologists working in Jerusalem find a huge skull with a hole in its forehead with “How’s about that, Goliath, you big hairy goon” scratched on the side of it, then we can say that we have evidence of the stories of David. Until then, we don’t have that.

Funnily enough, it’s to Professor Emeritus of Archaeology in the Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Civilizations at Tel Aviv University, Israel Finkelstein that we can turn to see a whole heap being made out of the inscription. Here’s what he wrote with Neil Asher Silberman in their book, The Bible Unearthed:

This is dramatic evidence of the fame of the Davidic dynasty less than a hundred years after the reign of David’s son Solomon. The fact that Judah (or perhaps its capital, Jerusalem) is referred to with only a mention of its ruling house is clear evidence that the reputation of David was not a literary invention of a much later period… the house of David was known throughout the region; this clearly validates the biblical description of a figure named David becoming the founder of the dynasty of Judahite kings in Jerusalem.6

When Finkelstein writes “Not a literary invention”, he is responding directly to the minimalist argument that the Bible’s historical books were written far too late to contain any historically reliable information –like, the Persian or even the Hellenistic era– and that their contents are literary fictions, as we heard before.

In fact, in The Quest for the Historical Israel, Finkelstein went further, saying that:

The mention of the “House of David” in the Tel Dan inscription from the ninth century B.C.E. leaves no doubt that David and Solomon were historical figures. And there is good reason to accept that many of the David stories in the books of Samuel—mainly the heroic tales and the description of his life as a bandit on the fringe of the Judean highlands—contain genuine, early historical memories.7

They’re some pretty strong statements!

Forgery!

Unsurprisingly, the discovery of the inscription and mention of the “House of David” was seen as serious egg on the minimalists’ faces. After all, as we saw a few minutes ago, it was only one year earlier that Philip Davies claimed that David was a “fiction” and a “literary creation”. As Halpern predicted:

Publication of the Tel Dan inscription will likely not lay the issue to rest.8

He wasn’t wrong. Only a few months later the first journal article casting doubt on the stele’s authenticity was published.

Frederick Cryer, of the University of Copenhagen, published an article entitled “On the recently‐discovered ‘house of David’ inscription” in the Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament. Here’s what he had to say:

Unhappily, there are grounds for scepticism in connexion with the present find. The first of these is, as mentioned before, that there are reasons for uncertainty as far as the find context of the fragment is concerned… A fourth feature to be considered is topicality. In ancient-historical research, as in the craft of the cloak-and-dagger spy, it is axiomatic that if one finds information just at the moment one needs it, it is very likely to be false… For the record, I doubt that the inscription is a forgery… But the matter will definitely bear further looking into.9

He gave a few reasons the inscription could be a fake, and then… said… it’s probably not. A couple of years later he was back at it:

Without putting too fine a point on it, the archaeological context of the find is uncertain…10

…but back-pedalled in the same article:

I took what should, properly considered, be the first step in dealing with any new epigraphic find of uncertain provenance, which is to say that I examined the question of the authenticity of the inscription,’ and arrived at a positive -if hesitant- evaluation.11

These nonsense claims of forgery petered out, with minimalist Niels Peter Lemche, Professor of Old Testament Studies at the University of Copenhagen, admitting that,

…the arguments in favour of seeing the Tel Dan fragments as fake need to be much more forceful—certainly stronger than I have been able to show in this survey—if they are to prove beyond doubt that the inscription is the work of a forger.12

The consensus is that the inscription is authentic - today it’s only on the extreme fringes that you’ll find anyone who thinks it’s a forgery.

As Professor of Ancient History and Archaeology at The George Washington University, Eric Cline writes,

…no serious scholar doubted the authenticity of the fragments.13

So, how did the minimalists try to discredit the significance of the find next? Backflips.

Minimalist backflips

Instead of accepting the plainly obvious meaning of the inscription, the minimalists wrote up a number of other ways to read “House of David”. Here’s what they came up with:

A place name

Frederick Cryer wrote that maybe “bethdawd” (i.e. ‘beit david’; the text ordinarily translated “House of David”) was the name used by the inscription’s author…

…for a geographical unit which may have been equivalent to all or some part of the region we regard as Judah.14

This is plain speculation. There’s no evidence for the idea that people from the time of the inscription referred to land of Judah as bethdawd. He’s pulled that straight out of the air.

Lemche and Thompson suggested that it,

may be a place somewhere in the vicinity of ancient Dan!15

Again, speculation. There’s nowhere in the area of Dan that’s called bethdawd.

In the same article they suggested that,

We would argue that it could also refer to the name of a holy place at Dan…16

More speculation. What other bright ideas did they have?

House of Uncle

Moving on from place names:

In the Bible DWD can mean “beloved” or “uncle,”…17

The house of Uncle!? Yeah, of a god called “Uncle”.

This option was addressed by the Professor of Egyptology at the University of Liverpool, Kenneth Kitchen, who wrote,

And what of this mysterious deity *Dod, trundled out again by some commentators on the Tel Dan stela? Surely the time has now come to celebrate *Dod’s funeral-permanently! There is not one scintilla of respectable, explicit evidence for his/her/its existence anywhere in the biblical and ancient Near Eastern world. No ancient king ever calls himself ’beloved of Dod’; no temple of Dod has ever been found, and clearly identified as such by first-hand inscriptions. We have no hymns to Dod, no offering-lists for Dod, no published rituals in any ancient language for Dod, no statues of Dod, no altars, vessels, nor any other ritual piece or votive object dedicated to Dod as a clear deity. Why? Because he/she/it never existed in antiquity, but is a modem invention by ingenious scholars from the last century…. Dod is a dud deity, as dead as the Dodo…18

“House of Uncle” is just jibber jabber.

What next? Probably my favourite…

House of Kettle

Davies wrote,

…one place [in the Bible] it means “kettle.” So a number of ways of understanding DWD present themselves, most of them more plausible than translating “David.”19

“House of Kettle”? More plausible than the obvious House of David?! Lol.

Davies wasn’t alone. Cryer wrote that there was an option,

…that has not as yet to my knowledge received attention is… “house of the cauldrons”…20

This stuff is just nonsense, and they admit as much. In 2003 Lemche wrote,

If a person is set on understand[ing] this term as a reference to the ‘House of David, extremely strong arguments are needed if a change of opinion is going to be brought about. And it is true to say that as yet we have not found such strong arguments. The arguments we possess may be good enough to convince a person who would like to be convinced, but hardly anybody else.21

As he says, their arguments aren’t strong, and the only people who accept them are those who would like to be convinced of them.

Mainstream scholars’ reactions to these weird interpretations

So, how did more mainstream scholars react to this? Well, it was quite funny for those looking on.

Halpern wrote,

The recent discovery… is causing extraordinary contortions among scholars who have maintained that the Bible’s history of the early Israelite monarchy is simply fiction.22

Professor of Near Eastern Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Arizona, William Dever, described the minimalists’ interpretations in similar ways saying that,

Several of the other revisionists have turned amusing intellectual somersaults to avoid the obvious meaning of the Dan inscription.23

That’s all pretty funny, but there were a few low blows. One example: Professor Emeritus of Ancient Near Eastern Cultures and Semitic Linguistics at Tel Aviv University, Anson Rainey, wrote an article with the subheading, “Davies is an amateur who ‘can safely be ignored’” saying that,

Davies’s objections are those of an amateur standing on the sidelines of epigraphic scholarship.24

Brutal. Another example was with Halpern again, this time being so amazed at the nonsense the minimalists suggested that he could only conclude that they were driven by non-academic motives:

One may question the motives of the hysteria—they differ in different scholars. In one the motivation may be a hatred of the Catholic Church, in another of Christianity, in another of the Jews, in another of all religion, in another of authority.25

I mean, it’s fair enough. If they knew their arguments weren’t strong and would only be believed by people who want to believe them, that’s hardly what scholarship is meant to be about, right? Still it was all pretty brutal.

So, after all was said and done, Dever summarised the situation well:

…regarding the authenticity of the inscription, we now have published opinions by most of the world’s leading epigraphers (none of whom is a “biblicist” in Thompson’s sense): the inscription means exactly what it says.26

…the “House of David”.

So, for the rest of this blog post, we’re going to stick with the consensus of the relevant scholars and carry on, accepting that the stele is legit - because it is, and that it really does mention the House of David - because it does.

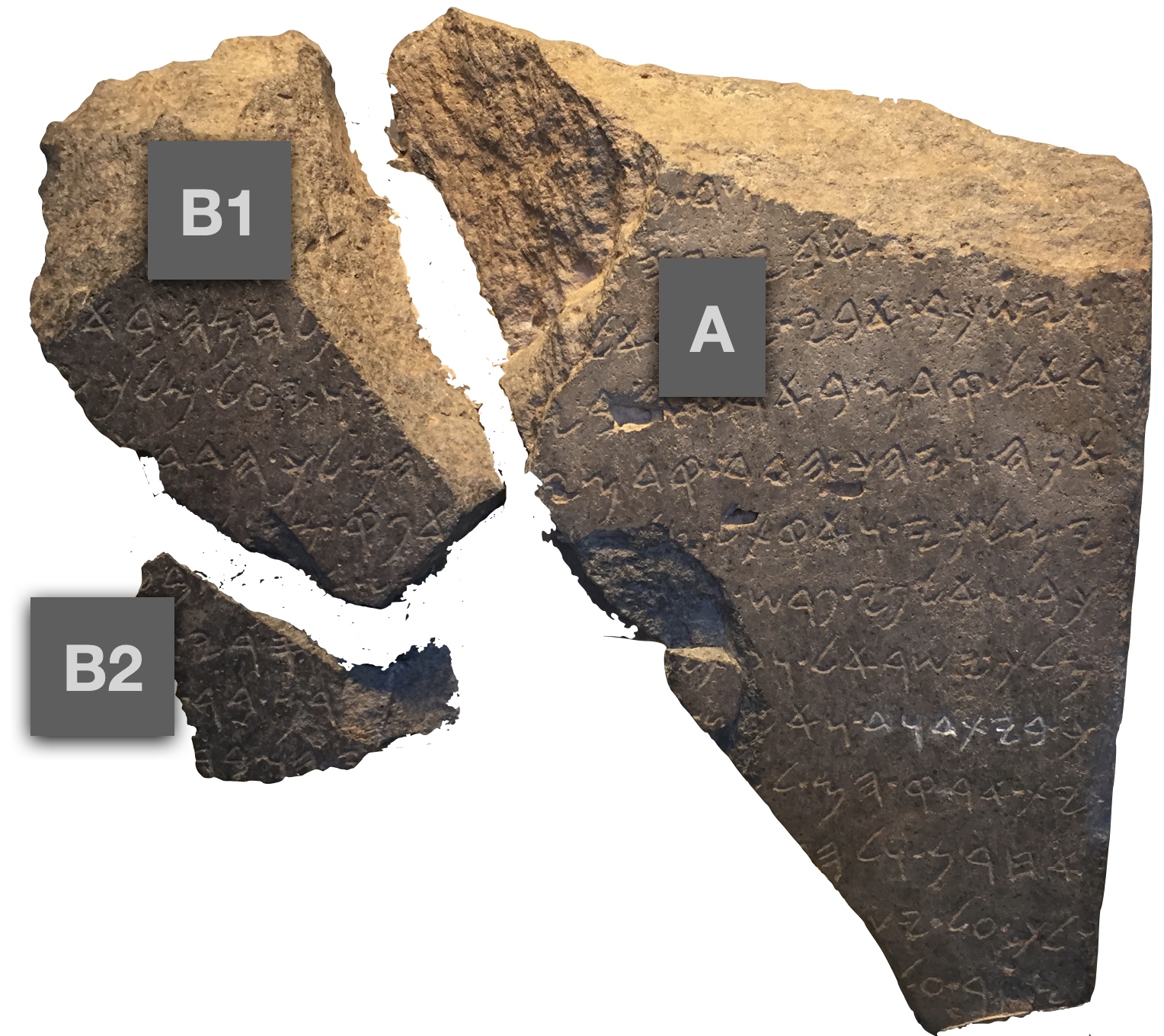

What really drove the last nails into the coffin of “it’s a forgery!”/“it says House of my uncle’s kettle!” was the discovery of two more pieces of the stele, 11 months after the first piece was found.

Discovery of the 2nd and 3rd portions of the Stele

The area just north of where the first piece of the stele was found was a whole load of debris. As it was being excavated they found what eventually turned out to be a “High Place”. 2 meters south of it, lying in the debris 80cm above the current ground level, the second piece of the stele was found by Area Supervisor Malka Hershkovitz. They called this new piece “B1”.27

Then, in the same excavation season, Gila Gook –who’d found the first piece of the stele– was excavating the pavement behind the “High Place”. As she stuck a measuring rod into the base of the wall she spotted a 3rd piece of the stele, which they called “B2”.28

And, to this day, that’s as much of the stele has been found.

Putting the pieces together

So, how did these 3 pieces relate? Well, Biran and Naveh found that B1 and B2, even though they were found 8 meters apart, fitted together perfectly29; and in a fascinating paper by Professor of Biblical Studies and Northwest Semitic Languages at the University of California, William Schniedewind says that B1 and B2 “make an obvious join” calling it “fragment B” (like pretty much everyone else).30

Schniedewind also says that the join between fragment A and B is “less certain”, but that,

This join forms a readable text with relatively minor difficulties.31

He goes on to explain that the join between fragment A and B that Biran and Naveh suggested is supported by the way the text lines up, matching the sort of phraseology found in inscriptions of this sort of genre.32

André Lemaire, a french epigrapher, Director of Studies at the École Pratique des Hautes Études also wrote saying,

…I have checked myself, in the Hebrew Union College museum, the placement of fragments A and B and I agree with the presentation of the editio princeps which seems to me the most probable, even if not practically certain.33

So, apart from a couple of scholars who say that either fragment A and B should be arranged vertically rather than side to side, or that they just aren’t related at all –suggested, no surprise, by our minimalist friend Cryer (who naturally says that it’s “a foregone conclusion that Dan A has nothing to do with Dan B”34), pretty much everyone goes with the arrangement suggested by Biran and Naveh in the article they published fragment B in.

So, we’ll continue following the consensus.

Before we get to what the text says, we need to know when the inscription was written.

Dating the inscription

As we’ve seen, the inscription was found in pieces, scattered across a relatively wide area. Obviously, that’s not how the stele originally stood. It would have been standing somewhere prominent so that people could read it –or, if they were illiterate, at least be impressed by it– before it got smashed up.

And, that’s how it was found - smashed into pieces. Not only was the inscription smashed, the pieces were found inside walls - they’d been used as filler to build those walls.

Based on that, it’s fair to say that the inscription must be older than the walls the pieces were found in - if the pieces are in a wall, they must have existed before the wall was built. You can’t make a wall out of pieces that don’t exist.

Then, since the wall was found smashed, the wall must have been built before it was smashed - again, simple logic.

Also, about the wall, it can’t be any older than the floor it was built on - the floor has to exist in order to build a wall on it. Also, the wall can’t be any newer than the date it was destroyed - it has to exist before it can be destroyed.

Based on that pretty simple set of rules, we can say that… since the wall fragment A was found in was destroyed in the 730s BCE by Tiglath Pileser III… and since the wall sits on a pavement that had lying on it pottery from the very late 9th century…

The inscription can’t be any newer than the late 9th century.35

William Dever36, Israel Finkelstein37, Kenneth Kitchen38, and William Schniedewind39 all agree. The stele must have been written somewhere in the late 9th century - sometime in the 840s BCE.

So, what does the inscription say?

Reconstruction of the “full” text

Biran and Naveh published a complete reconstruction of the text in the article they wrote on fragments B1 and B2.40 Here it is:

- [….] and cut [… ]

- […] my father went up [against him when] he fought at [… ]

- And my father lay down, he went to his [ancestors] (viz. became sick and died). And the king of I[s-]

- rael entered previously in my father’s land. [And] Hadad made me king.

- And Hadad went in front of me, [and] I departed from [the] seven […-]

- s of my kingdom, and I slew [seve]nty kin[gs], who harnessed thou[sands of cha-]

- riots and thousands of horsemen (or: horses). [I killed Jeho]ram son of [Ahab]

- king of Israel, and [I] killed [Ahaz]iahu son of [Jehoram kin-]

- g of the House of David. And I set [their towns into ruins and turned]

- their land into [desolation … ]

- other [… and Jehu ru-]

- led over Is[rael … and I laid]

- siege upon [ … ]

It’s written in a dialect of Old Aramaic41, and even without the “House of David” bit it’s a massively significant find for those who study the way Aramaic developed over time and in different areas.

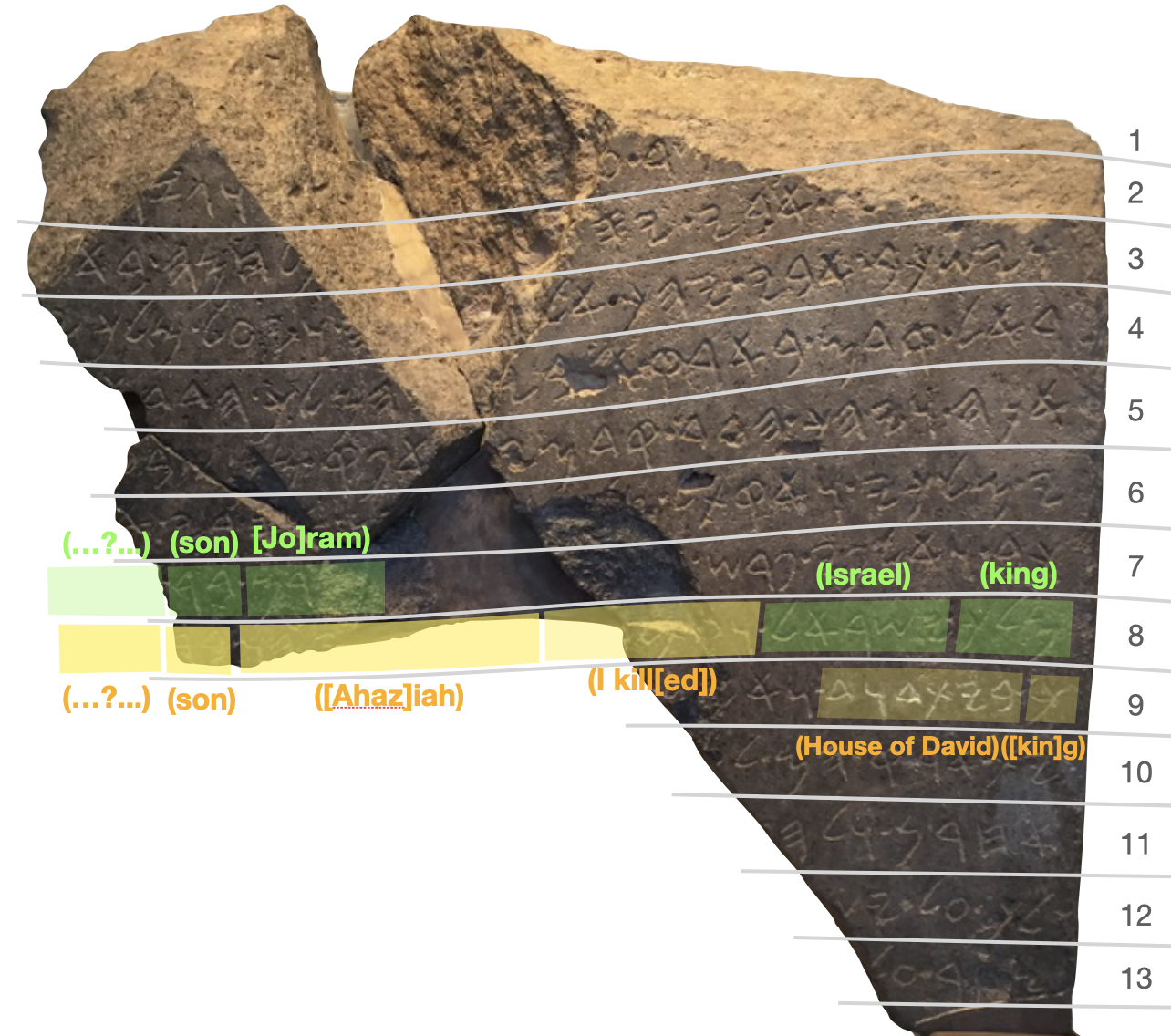

There is a whole ton of fascinating stuff in the inscription, but what we’re going to concentrate on in this post are lines 7, 8, and 9. Because, though finding “House of David” was cool, it’s the what the rest of the sentence it was found in says that should make Christians sit up and pay attention.

Ahaziah and Joram named

So, those lines –7 though 9– though they’re fragmentary, they can be reliably reconstructed. And what we’ll see when we read the scholarship on it is that those lines contain mention of the names “Ahaziah” and “Joram”. Let’s take a look at how the relevant scholars come up with that.

Lines 7 & 8 say: “[somebody]…ram son of [somebody…] king of Israel”

The “King of Israel” bit is very clear - but which king is it talking about?

The only king, either of Israel or of Judah, whose name ends with resh and mem is Jehoram.42

Jehoram, AKA, Joram’s place in the biblical chronology fits the dating of the stele.

Moving on…

Lines 8-9: “I kill[ed] [somebody]…yahu son of … [kin]g of the House of David.”

The “king” reconstruction isn’t certain - it’s only the 3rd of the 3 letters that make up melech that have been preserved, and not all scholars accept the reconstruction, though most seem to.

“Yahu” is the ending of a Hebrew theophoric name.43 It’s a royal name (it’s followed by “of the house of David”, so the “king of” reconstruction doesn’t matter either way), so which royal in the 9th century had a name ending in “yahu”? There’s only one real candidate: Ahaziah (Hebrew pronunciation: “Achazyahu”):

The name Ahaziah was borne by both a king of Israel and a king of Judah, but only one can be taken into consideration: the son of Jehoram and grandson of Jehoshaphat…44

The reading of Joram and Ahaziah, though fragmentary, is solid enough that Professor of Northwest Semitic Languages and Literatures at George Washington University, Christopher Rollston writes of the inscription:

Some details, nevertheless, are preserved. Namely, Hazael states that he killed King Jehoram son of Ahab the king of Israel and that he killed King Ahaziah son of Jehoram king of the House of David (i.e., Judah).45

Those who remember their Sunday School lessons will remember that these two characters appear in 2 Kings 8:28:

“[Ahaziah] went with Joram son of Ahab to wage war against King Hazael of Aram at Ramoth-gilead…”

Based on this (and a couple of other clues in the rest of the inscription), scholars have concluded that the author of the stele was Hazael. As Biran and Naveh wrote,

The text … clearly indicates that the author of the stele was Hazael himself, although his name does not appear in the fragments found to date.46

Hazael is well known in historical records, for example there’s an inscription on a basalt statue written by Shalmaneser III. He clearly didn’t think much of Hazael…

Hazael, son of nobody, seized the throne, called up a numerous army and rose against me.47

It’s the consensus position that Hazael, this “son of nobody”, was the Tel Dan stele’s author.

So, that’s all cool. We’ve got a “House of David”, “Ahaziah”, and “Joram” in an inscription written by Hazael. That’s pretty awesome.

But this is where we need to go beyond apologetics.

What we’ve got in The Tel Dan inscription is, as we’ve already said, a claim. The claim is that Hazael killed Joram king of Israel, and Ahaziah king of the House of David.

Now, scripture records the death of these two characters, and here’s the fun bit: it wasn’t at the hand of Hazael.

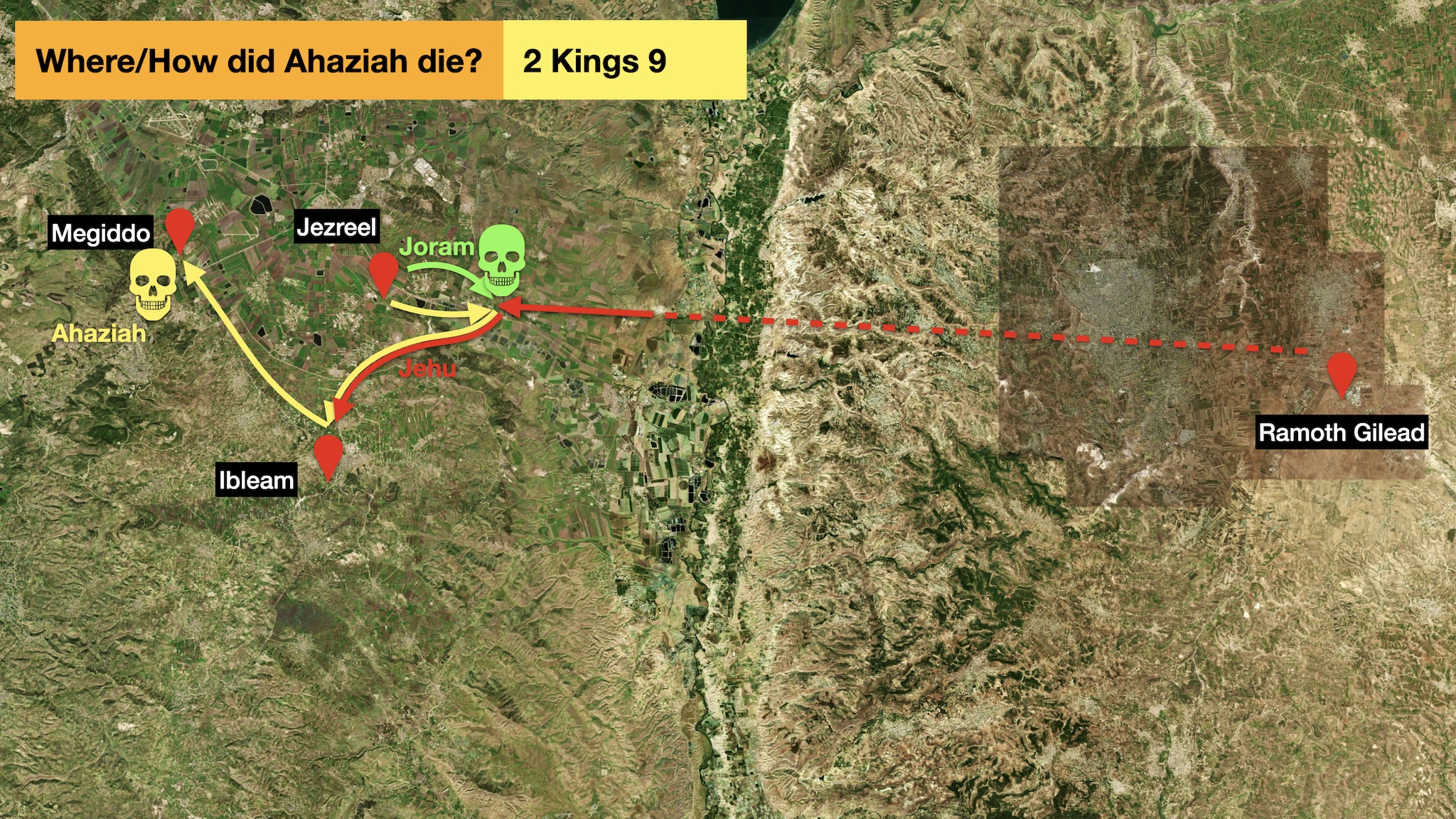

The scriptural record of Joram and Ahaziah’s deaths is in 2 Kings 9. A happy Sunday School story :)

The biblical description of events in 2 Ki 8:25-9:28

We’re going to summarise chapter 8:25 to 9:28 - and follow the action on a map…

Also, since the family trees involved here are pretty hairy we’ll put them to one side and stick with the action.

- At the age of 22, Ahaziah becomes king of Judah during the 12th year of the reign of the Israelite King Joram son of Ahab,

- 2 Ki 8:28 Joram and Ahaziah team up and go to the city of Ramoth Gilead (Tell er-Rumeith) to fight Hazael, the king of Aram (roughly in the area of modern Syria, with its capital at Damascus)

- 2 Ki 8:29 Joram takes a beating and goes to the city of Jezreel to recover, leaving the Israelite army still at Ramoth Gilead

- 2 Ki 8:29 and Ahaziah goes there to pay Joram a visit

- 2 Ki 9:1 Elisha, a prophet in Israel tells one of his prophetic band to go to Ramoth Gilead (where Joram had just received a beating), and anoint a guy called Jehu as king of Israel to take the place of Joram (Jehu seems to be some sort of high-ranking military guy)

- 2 Ki 9:4-10 The prophet goes to Ramoth Gilead, asks for Jehu, anoints him, and tells him to wipe out Joram and the rest of the descendants of Ahab (Joram’s father)

- 2 Ki 9:7-10 He explains that the reason for this is to get revenge on Jezebel - Joram’s mother, Ahab’s wife - who’d wiped out Israelite prophets.

- 2 Ki 9:15-16 To prevent word getting out Jehu gets the army officers to make sure that no one leaves Ramoth Gilead, and he heads off in his chariot with some of his men to pay Joram a visit in Jezreel

- 2 Ki 9:17 Meanwhile, a lookout in Jezreel tells Joram that he sees a troop heading towards the city. Joram sends a messenger on horseback to the oncoming troop to ask if everything is OK.

- 2 Ki 9:18 Jehu tells the messenger that it’s none of his concern and to fall in behind him, which he does.

- 2 Ki 9:19-20 Joram sends out another messenger, but the same thing happens. The lookout reports that he recognises Jehu’s chariot driving style - “like a maniac”.

- 2 Ki 9:21-22 Joram and Ahaziah both jump into their chariots and ride out to meet Jehu. When they meet, Joram asks Jehu if he’s coming in peace. Jehu responds that there will not be peace while Joram’s mother Jezebel continues to practice witchcraft and idolatry.

- 2 Ki 9:24 Jehu then shoots Joram in the heart, killing him.

- 2 Ki 9:27 When Ahaziah sees this he flees almost due south, probably heading back to his southern kingdom of Judah, but Jehu chases him (around ~13km!), catches up with him next to a place called Ibleam, and shoots him. The arrow doesn’t kill Ahaziah immediately. Instead Ahaziah turns around and heads north-west for Megiddo. He reaches the city, but dies there shortly thereafter.

A contradiction

Clearly, this doesn’t line up with the inscription on the Tel Dan stele.

Scripture says that Joram and Ahaziah were killed by Jehu, but the inscription says they were killed by Hazael. This seems plainly contradictory - they were either killed by one or the other (or neither!).

This, at least as far as I can tell, was one of only a few useful thing the minimalists pointed out. Here’s what Davies had to say:

…it’s a bit mischievous even to raise the possibility of a parallel between the Dan inscription and the Bible without conceding that such a parallel must show the Biblical account to be in error!48

More mainstream scholars pointed out the same thing - here’s Halpern:

…the text can be best deployed both against the revisionists and against the conservatives as a strong argument that our texts are neither entirely unreliable nor complete or reliable in detail.49

So, how do we deal with the fact that scripture says one thing about who killed Joram and Ahaziah, and the inscription another? As Professor of History and Humanities at York University in Toronto Carl Ehrlich pointedly states,

…maximalists are faced with having to attempt to harmonize seemingly conflicting pieces of evidence in this case.50

Dealt with?

The articles we’ve been quoting from haven’t missed this contradiction - most of them have addressed it directly:

Biran and Naveh asked,

Is it possible that Hazael saw Jehu as his agent?51

Professor Emeritus of Old Testament at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago, Ralph Klein writes in his Hermeneia commentary,

If Jehu were acting as an agent of Hazael or was his vassal, Hazael could claim responsibility for these assassinations even though Jehu or his men did the actual killing.52

I mean, this sort of explanation would fit nicely with what some Christians think of as a “high” view of scripture and inerrancy, where historical information in the Bible must be accurate and reliable. The explanation that both Jehu and Hazael could legitimately claim to have killed the two kings because one worked for the other allows for both sources being “right”, or “correct”, or “true”.

Sticking with the inerrancy discussion, you could also say that the Bible is “right” and Hazael’s inscription is “wrong”, and go on your merry way – Hazael being a liar doesn’t have any effect on biblical inerrancy.

And, if that’s what you need, fine. Read it that way. But, stop reading this post now, because things are about to get complicated…

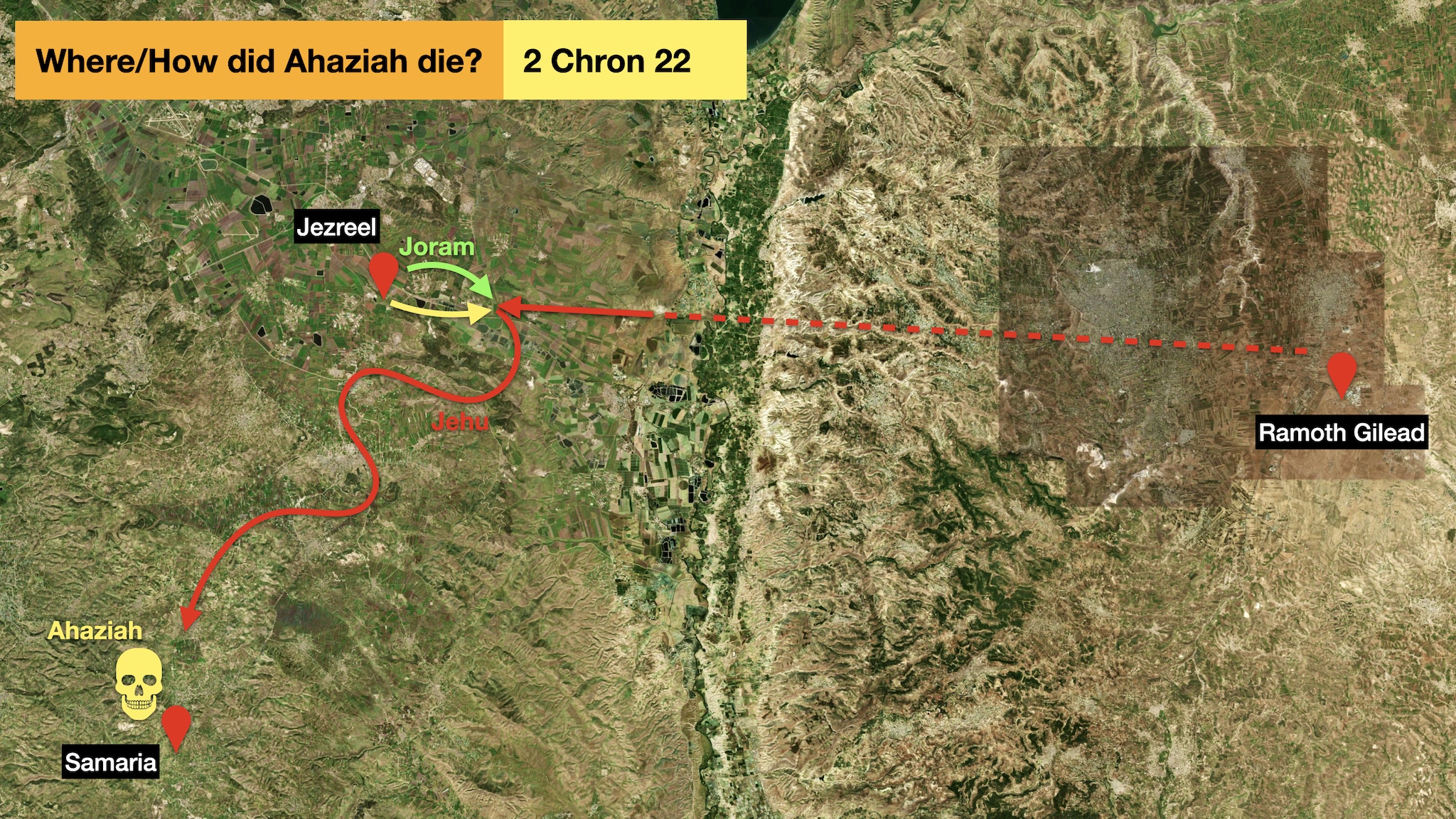

Why? Because 2 Kings 9 has a parallel account in 2 Chronicles 22…

The parallel account in 2 Chronicles 22

Like we did for 2 Kings 9, here’s a summary of the action in 2 Chronicles 22 (and thankfully, it’s a lot shorter):

- 2 Chr 22:7 Ahaziah goes out with Joram to meet Jehu

- 2 Chr 22:8 While wiping out Joram’s extended family, Jehu comes across Ahaziah’s nephews and officials, and kills them too

- 2 Chr 22:9 Jehu then goes looking for Ahaziah, who’d been captured hiding in Samaria. He was brought to Jehu who executed him.

That is quite… “different”. Putting aside the inscription on the Tel Dan stele for a moment, what we’ve got here is a contradiction between two Biblical narratives from parts of the Bible we commonly think of primarily as history writing:

- In 2 Kings Ahaziah dies from his wounds in Megiddo after fleeing there from Ibleam

- In 2 Chronicles Ahaziah is executed by Jehu after hiding in Samaria

It can’t be both!

If you read the two passages carefully you’ll find other details that can’t be made to fit either but we won’t get into that here.

See? Beyond apologetics. We’re out of the comfortable world of archaeology “proving the Bible” with the “House of David” inscription, and we’re now in considerably more murky waters dealing with a flat contradiction between two biblical texts.

This stuff is way more interesting than apologetics, at least to me :)

On Biblical contradictions

So, a quick word on Biblical contradictions (and i’m going to write something on contradictions another time and get into some detail then) so I’ll keep it brief for now…

First of all, I’m not talking about “contradictions” which can just be explained away as “differences”. I’m talking about flat contradictions, where only one of two statements can be true.

So. From the first time a biblical text was written down until the printing press was invented, biblical texts were copied out by hand. This means literally thousands of people have had a chance to notice and iron out contradictions - thousands of people over hundreds and hundreds of years. That these contradictions have survived down to this day tells us something: until only relatively recently, with a couple of humorous exceptions, no one cared about Biblical contradictions.

As Professor of Old Testament Criticism and Interpretation at Yale Divinity School, John J. Collins wrote in his Introduction to the Hebrew Bible:

It is typical of biblical literature that these tensions in the text were not smoothed out by a final editor, but were allowed to stand, allowing us to see some of the diverse perspectives that shaped these books.53

Caring about contradictions is a new thing. Reading the Bible in ways that depend on it being free of contradictions is just not what people did.

If you’re reading the Bible that way, being worried about “contradictions” says more about your approach to the text than the text itself.

Why? Because the important realisation we need to have is this:

Back in the day, no one wrote dispassionate, objective histories. No one wrote history just for the fun of it. No one wrote history just to keep accurate historical records of events. It just wasn’t their concern. And everyone knew that. So no one expected it.

Writers wrote for a specific purpose, with a specific audience in mind. They used sources, but they used them in ways that suited their purposes. So, when we figure out what those purposes were, we can see why they narrated events in the ways they did.

Worrying about “contradictions” kinda misses the point.

OK, back on topic…

Authorial intent

What’s with the contradictions in the two passages we’re looking at? Well, as we’ve said, it’s down to the fact that they weren’t writing history as we think of it. They weren’t trying to make their records line up. Our three writers –Hazael, the author of Kings, and the author of Chronicles– were each writing with very specific intents and purposes.

Hazael’s purpose for writing

Let’s start with Hazael’s inscription on the Tel Dan stele.

Scholars are in agreement that the Tel Dan stele is a “Memorial stele”.5455

Associate Professor at the Centre for Jewish Studies at the University of Maryland, Matthew Suriano, wrote a paper that goes into this stuff in a ton of detail. In it he lists off the elements that make up the Memorial Stele genre.56 They are:

- Historical reference to predecessors and their failures (lines 2–4)

- Validation through succession (line 3)

- Validation through “divine election” (lines 4 and 5)

- Elimination of all claimants to power (line 6)

- Justification through military prowess (lines 7–13)

(We’ve been looking at lines in that final 5th point.)

It turns out that the Tel Dan stele is a great example of this genre. So, what were texts written in this genre all about? Schniedewind explains that the stele,

…was intended as propaganda boasting of Hazael’s victories on the northern border of Israel.57

It’s straight up self-promotion. It’s all about cementing the legitimacy of your rule in the minds of your subjects by appealing to your achievements. Rulers would exaggerate, spin, and tell all sorts of tall tales in these Memorial Steles. If you’re looking for unbiased history, Memorial steles aren’t what you want.

So, based purely on the Tel Dan stele, there’s no reason to think that it was definitely Hazael who defeated Joram and Ahaziah instead of Jehu, and there’s no reason to think that it couldn’t have been Jehu who killed them while working for Hazael, and there’s no reason to think that it couldn’t have been Jehu killing them because one of Elisha’s prophets told him to. The Tel Dan stele just isn’t the sort of historically reliable source you need to make that sort of judgement - it doesn’t rule out anything.

So, that’s Hazael’s purpose. What about the author of Kings?

The Deuteronomist’s purpose for writing

We’re going to deal with it in another post, but just quickly, the book of Kings is part of a collection of biblical books known as the Deuteronomistic History, made up of Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings.

Along with the book of Deuteronomy, it was written in two editions - the first was written in the time of King Josiah by scribes of the “Deuteronomistic school” in Jerusalem, and the second edition was edited during the exile - the final chapter of the book mentions events that happened several decades into the exile.

Of course, the scribes of the Deuteronomistic school used older traditions and sources that went back, in some cases, hundreds of years, but the writings are essentially from the end of the 1st temple period and into the exile.58

That being the case, there’s a time gap of somewhere between 200 and 250 years between the death of Joram and Ahaziah, and the time the Deuteronomistic History was put together. That doesn’t mean that the text is necessarily historically unreliable, it’s just to say that it wasn’t written by an eye witness to the events it records.

For us, the important bit to realise is that though the historical accuracy of some of the writers’ reports are incredibly accurate over long stretches of time, that wasn’t what they were aiming for. It wasn’t their purpose. It wasn’t their interest.

The writers of the Deuteronomistic school had a specific purpose in writing – to provide a reconstruction of Israel’s history as seen through the lens of their book of the Law - Deuteronomy. Collins explains that,

…the reconstruction of the history of Israel in these books has a clear ideological character. It is heavily influenced by Deuteronomic theology, and sees a pattern of reward and punishment in history…59

Anyone reading Joshua, Judges, Samuel, or Kings will have noticed that theme. Those books are infused with the idea that God was rewarding or punishing the Israelites’ good or bad behaviour.

But on how historically accurate those reports were, at least by the standards we expect today, Collins goes on to explain that,

We should not doubt that these writers tried to give an accurate account of the past, as they understood it. But they also clearly wanted to convey a theological understanding of history, the belief that the course of events is shaped by God in response to human actions. This theological aspect of these books is as important for the modern reader as any historical information they contain.60

History was secondary to their primary interest of theology.

When it comes to our passage in 2 Kings, this theme is very clear indeed. The prophet sent by Elisha to Ramoth Gilead told Jehu that the reason he was being made king was so that he should,

2 Ki 9:7 …strike down the house of your master Ahab, so that I may avenge on Jezebel the blood of my servants the prophets, and the blood of all the servants of the Lord.

This was all in response to what Ahab and Jezebel had done. Back in 1 Kings 21 we find Elijah prophesying the end of Jezebel, and the entire house of Ahab.

1 Ki 21:21–24 I will bring disaster on you; I will consume you, and will cut off from Ahab every male, bond or free, in Israel; and I will make your house like the house of Jeroboam son of Nebat, and like the house of Baasha son of Ahijah, because you have provoked me to anger and have caused Israel to sin. Also concerning Jezebel the Lord said, ‘The dogs shall eat Jezebel within the bounds of Jezreel.’ Anyone belonging to Ahab who dies in the city the dogs shall eat; and anyone of his who dies in the open country the birds of the air shall eat.”

And what we have in 2 Kings 9 (and 10) is the fulfilment of that prophecy. Jehu may have been Hazael’s instrument, but this passage very much has him as God’s instrument for bringing about vengeance on Ahab and Jezebel.

Jehu kills Joram, the son of Ahab, he kills Jezebel, and and he kills all of Ahab’s descendants. The note about Ahaziah’s limping to his death in Megiddo is almost incidental. The Deuteronomistic writer here is interested in how God arranged for the end of Ahab and Jezebel’s influence on the people of Israel.

So, theological considerations aside, is the record in 2 Kings 9 historically accurate? Again, it’s hard to say. The writer seems very keen to either interpret events in light of his Deuteronomic theology, or to embellish events that same way.

Ok, so that’s the Deuteronomist. What about our final version of events? Let’s take a look at the passage in Chronicles.

The Chronicler’s purpose for writing

First, it’s worth mentioning that Chronicles was written way later than the Deuteronomistic history. In 1 Chronicles 3 we get a genealogy that runs for 6 generations after the return from exile, so Chronicles must have been completed, at the earliest, in around 400 BCE, about the time of that 6th generation. That’s around 150-200 years after the completion of the Deuteronomistic History.61

Though superficially we’re dealing with the same event, we’ve seen there are irreconcilable differences between what we find in Chronicles and what we find in Kings.

Undoubtedly, the writer of Chronicles, known as the “Chronicler”, had a copy of the book of Kings to refer to - he quotes from it often enough. So when he wrote what he did, he knew he was going off script. As Collins explains,

…the great bulk of the cases where [the Chronicler] departs from the Deuteronomistic History can be explained by his theological and ideological preferences.62

Senior Lecturer in Ariel University’s Israel Heritage Department David Rothstein explains one of these preferences in the Jewish Study Bible:

Chronicles discusses the fortunes of the northern monarchy only to the extent that they impact on Judah.63

Our passage in 2 Chronicles 22 is a great example: Joram the king of Israel only appears because the circumstance surrounding his death is the context in which Ahaziah’s death was brought about. There’s no mention of Elisha’s prophet anointing Jehu, there’s nothing about Ahab and Jezebel’s terrible influence on Israel. Joram and co are just background noise.

And, that’s because Ahaziah’s death is what the Chronicler is interested in.

That’s why he changes the order of events. As Ralph Klein wrote in his commentary on Chronicles,

…the Chronicler reversed the order because he wanted to make the death of Ahaziah the climax of his account.64

He doesn’t leave Ahaziah’s death to chance - in his narrative the Chronicler doesn’t allow him to limp off to Megiddo. He has him cut down by Jehu on the spot. An altogether different spot. And as the climax of that narrative, not some footnote.

The Chronicler was interested above all other things in the centrality and primacy of the Jerusalem Temple and the system of worship that took place there. He measured the kings of Judah by how well they maintained that system. David was awesome because he prepared for the building of the Temple. Solomon was awesome because he built the temple. All the kings that followed were measured against how closely they were aligned to that interest.

We’ll look at just one example: Ahaziah’s father. In 2 Chronicles 21, the previous chapter, we read that,

2 Ch 21:11 …he made high places in the hill country of Judah, and led the inhabitants of Jerusalem into unfaithfulness…

He went directly against the centralisation of worship at Jerusalem. So, what happened to him? The Chronicler describes his end like this - one of my favourite passages in the whole Bible:

2 Ch 21:18–20 After all this the Lord struck him in his bowels with an incurable disease. In course of time, at the end of two years, his bowels came out because of the disease, and he died in great agony. His people made no fire in his honor, like the fires made for his ancestors… He departed with no one’s regret. They buried him in the city of David, but not in the tombs of the kings.

That’s about as brutal a summary of anyone in the whole Bible. In the eyes of the Chronicler, this guy was a nobody, and everyone had to know it.

So how did that guys son, Ahaziah, measure up? In verse 4 we read,

2 Ch 22:4 He did what was evil in the sight of the Lord, as the house of Ahab had done…

What had Ahab done? We’ve got to turn back to 1 Kings to hear about Ahab:

1 Ki 16:30–33 Ahab son of Omri did evil in the sight of the Lord more than all who were before him… [he] went and served Baal, and worshiped him. He erected an altar for Baal in the house of Baal, which he built in Samaria. Ahab also made a sacred pole. Ahab did more to provoke the anger of the Lord, the God of Israel, than had all the kings of Israel who were before him.

Ahab was basically the anti-Chronicler. And the Chronicler saw Ahaziah as being as bad as Ahab. Clearly, Ahaziah had to die, and his death had to be a judgement from God. Moping off to Megiddo to die quietly in a corner wouldn’t cut it. So, the Chronicler arranges his Ahaziah narrative such that there’s a crescendo that ends with Ahaziah’s execution. That it was Jehu that performed it didn’t really matter. That it happened at the same time as Joram’s death didn’t really matter. For the Chronicler, it was all about God judging an unfaithful Judahite king who should have known better than to sink to Ahab’s level. An example needed to be made of him.

But for whose benefit? For the benefit of those the Chronicler was writing: people living in the early Second Temple period who the Chronicler also wanted to show fidelity to the Jerusalem Temple and its system of worship - only this time, the 2nd temple, not the 1st.

Summary of the measure of Historicity

So, we’ve looked at Hazael’s account on the Tel Dan stele. We’ve looked at the Deuteronomist’s account in 2 Kings. And we’ve looked at the Chronicler’s account in 2 Chronicles. Where does all this leave us? Everyone agrees that Joram and Ahaziah were killed, but we’ve got conflicting claims about who killed them, where, and how. With our three sources, can we get any clarity on what actually happened?

No. We just can’t with 100% confidence know who killed Joram and Ahaziah, though we can be pretty confident that Joram and Ahaziah died in a way they probably weren’t all that keen on. We can’t know for sure how Jehu fits into all this - did he work for Hazael? Did he mortally wound Ahaziah at Ibleam, or did he execute him in Samaria?

We just don’t know. The facts of the events are beyond our reach. They’re pretty much lost to history. We’ve got three different writers, each writing accounts of an event that was too important to them to leave uninterpreted, unspun, or unused to further their agenda.

And that for me is the takeaway from all this.

Writers had agendas. They do today and they did back then. Facts are secondary, message is everything. And when three different writers have one set of facts but three different purposes for writing, historical accuracy is going to struggle to survive through the process of writing those texts. We can’t assume that everything we read in the “Historical Books” of the Bible is plain history - the authors weren’t all that interested in historical accuracy. They were interested primarily in theology.

And this is where things can really make a difference to the way we engage with the Bible.

Reading the Bible Better

If it’s important to you that there are no contradictions in the Bible, then you’re concerned about something the biblical writers weren’t concerned about. If we read the Bible with that expectation,

- We’re going to be disappointed, and,

- We’re going to completely miss the message the authors were aiming to get across.

Instead of worrying about contradictions –that almost no one cared about until only relatively recently, because people back then knew better than to worry about contradictions– let’s use contradictions as a reminder to engage with the biblical texts as their authors intended us to engage with them. They were writing theology, so let’s concentrate on the theology. 100% historical accuracy was not a priority for the writers of the historical books, so let it also be a low priority in our reading. Let’s pay more attention to the primary interest of the biblical writers, which was theology.

When we read the book of Kings, let’s focus on reading it through the lens of the Deuteronomistic writers living at the end of the 1st Temple period and in the exile. Follow the Deuteronomist’s plot of how God rewarded or punished the activity of the kings of his people, not the plot our modern culture has programmed us to think is there. Don’t worry about things the writers didn’t concern themselves with.

When we read the book of Chronicles, let’s focus on reading it from the point of view of the Chronicler, who lived several generations into the return from exile. He wasn’t writing at the same time as the Deuteronomist, and he was interested in very different things, writing for a very different audience. His overriding interest was in Temple worship, and in his writings measured people against the standard of fidelity to Temple worship.

Zooming out a little from Kings and Chronicles, to properly understand any biblical passage we’ve got to work out who wrote the passage, why they wrote it, when they wrote it, and for who. Without that information, we’re going to struggle to get the message the author was trying to convey. But when we do have that information, we’ll do a much better job at interpreting the Bible.

Conclusion

So, the Tel Dan Stele. Apologists are right that the House of David bit is cool, but when we go beyond apologetics we’ll find so much more that’s useful if we’ll let our assumptions be challenged by it and what it points to.

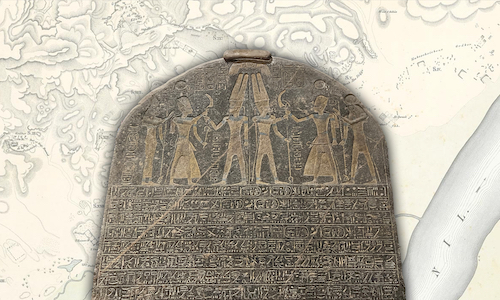

Featured image

The Tel Dan Stele superimposed on the Survey of Israel map of the relevant area.

Footnotes

-

Philip R. Davies, In Search of Ancient Israel, 2nd edition (Bloomsbury, 2015), 57. (Originally published in 1992, a year before the first fragment was discovered) ↩

-

Philip R. Davies, In Search of Ancient Israel, 2nd edition (Bloomsbury, 2015), 18. (Originally published in 1992, a year before the first fragment was discovered) ↩

-

Events reconstructed from various sources: Hershel Shanks, “Happy Accident: David Inscription,” Biblical Archaeology Review (September/October), Vol. 31, No. 5 (2005): 46. Avraham Biran, “‘David’ Found at Dan,” Biblical Archaeology Review (March/April), Vol. 20, No. 2 (1994): 33. Avraham Biran & Joseph Naveh, “An Aramaic Stele Fragment from Tel Dan,” Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 43, No. 2/3 (1993): 84. ↩

-

Avraham Biran & Joseph Naveh, “An Aramaic Stele Fragment from Tel Dan,” Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 43, No. 2/3 (1993): 90. ↩

-

Baruch Halpern, “Erasing History,” Bible Review (December), Vol. 11, No. 6 (1995): 35. ↩

-

Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman, The Bible Unearthed (Free Press, 2002), 129. ↩

-

Israel Finkelstein, “King Solomon’s Golden Age: History or Myth?,” in The Quest for the Historical Israel, ed. Brian B. Schmidt (Brill, 2007), 114-115. ↩

-

Baruch Halpern, “The Stela from Dan: Epigraphic and Historical Considerations,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (November), no. 296 (1994): 63. ↩

-

Frederick H. Cryer, “On the recently‐discovered “house of David” inscription,” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament (February), Vol. 8, No. 1 (1994): 14-15. ↩

-

Frederick H. Cryer, “Of Epistemology, Northwest-Semitic Epigraphy and Irony: the ‘Bytdwd/House of David’ Inscription Revisited,” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament (March), Vol. 21, No. 69 (1996): 4-5. ↩

-

Frederick H. Cryer, “Of Epistemology, Northwest-Semitic Epigraphy and Irony: the ‘Bytdwd/House of David’ Inscription Revisited,” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament (March), Vol. 21, No. 69 (1996): 6. ↩

-

Niels Peter Lemche, “‘House of David’: The Tel Dan Inscription(s),” in Jerusalem in Ancient History and Tradition, ed. Thomas L. Thompson (T&T Clark, 2003), 66. ↩

-

Eric H. Cline, Biblical Archaeology: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2009), 61. ↩

-

Frederick H. Cryer, “On the recently‐discovered “house of David” inscription,” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament (February), Vol. 8, No. 1 (1994): 16-17. ↩

-

Niels Peter Lemche & Thomas L. Thompson, “Did Biran Kill David?,” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, Vol. 64 (1994): 10. ↩

-

Niels Peter Lemche & Thomas L. Thompson, “Did Biran Kill David?,” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, Vol. 64 (1994): 13. ↩

-

Philip R. Davies, “‘House of David’ Built on Sand: The Sins of the Biblical Maximizers,” Biblical Archaeology Review (July/August), Vol. 20, No.4 (1994): 55. ↩

-

Kenneth A. Kitchen, “A Possible Mention of David in the Late Tenth Century BCE, and Deity Dod as Dead as the Dodo?,” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, Vol. 76 (1997): 41-42. ↩

-

Philip R. Davies, “‘House of David’ Built on Sand: The Sins of the Biblical Maximizers,” Biblical Archaeology Review (July/August), Vol. 20, No.4 (1994): 55. ↩

-

Frederick H. Cryer, “A ‘Betdawd miscellany: DWD, DWD’ or DWDH?,” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament (February), Vol. 9, No. 1 (1995): 54. ↩

-

Niels Peter Lemche, “‘House of David’: The Tel Dan Inscription(s),” in Jerusalem in Ancient History and Tradition, ed. Thomas L. Thompson (T&T Clark, 2003), 66. ↩

-

Baruch Halpern, “Erasing History,” Bible Review (December), Vol. 11, No. 6 (1995): 26. ↩

-

William G. Dever, What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It?: What Archaeology Can Tell Us about the Reality of Ancient Israel (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2002), 30. ↩

-

Anson F. Rainey, “The ‘House of David’ and the House of the Deconstructionists,” Biblical Archaeology Review (March/April), Vol. 20, No. 6 (1994): 47. ↩

-

Baruch Halpern, “Erasing History,” Bible Review (December), Vol. 11, No. 6 (1995): 35. ↩

-

William G. Dever, What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It?: What Archaeology Can Tell Us about the Reality of Ancient Israel (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2002), 128–129. ↩

-

Avraham Biran and Joseph Naveh, “The Tel Dan Inscription: A New Fragment,” Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 45, No. 1 (1995): 2. ↩

-

Avraham Biran and Joseph Naveh, “The Tel Dan Inscription: A New Fragment,” Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 45, No. 1 (1995): 5. ↩

-

Avraham Biran and Joseph Naveh, “The Tel Dan Inscription: A New Fragment,” Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 45, No. 1 (1995): 9. ↩

-

William M. Schniedewind, “Tel Dan Stela: New Light on Aramaic and Jehu’s Revolt,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (May), no. 302 (1996): 78. ↩

-

William M. Schniedewind, “Tel Dan Stela: New Light on Aramaic and Jehu’s Revolt,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (May), no. 302 (1996): 78. ↩

-

William M. Schniedewind, “Tel Dan Stela: New Light on Aramaic and Jehu’s Revolt,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (May), no. 302 (1996): 78. ↩

-

André Lemaire, “The Tel Dan Stela as a Piece of Royal Historiography,” Journal for the Study of the Old Testament, Vol. 81 (1998): 3. ↩

-

Frederick H. Cryer, “A ‘Betdawd miscellany: DWD, DWD’ or DWDH?,” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament (February), Vol. 9, No. 1 (1995): 54.) ↩

-

Baruch Halpern, “The Stela from Dan: Epigraphic and Historical Considerations,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (November), no. 296 (1994): 68. ↩

-

William G. Dever, What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It?: What Archaeology Can Tell Us about the Reality of Ancient Israel (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2002), 128. ↩

-

Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman, The Bible Unearthed (Free Press, 2002), 129. ↩

-

K. A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2006), 37. ↩

-

William M. Schniedewind, “Tel Dan Stela: New Light on Aramaic and Jehu’s Revolt,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (May), no. 302 (1996): 75. ↩

-

Avraham Biran and Joseph Naveh, “The Tel Dan Inscription: A New Fragment,” Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 45, No. 1 (1995): 13. ↩

-

William M. Schniedewind, “Tel Dan Stela: New Light on Aramaic and Jehu’s Revolt,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (May), no. 302 (1996): 81. ↩

-

Avraham Biran and Joseph Naveh, “The Tel Dan Inscription: A New Fragment,” Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 45, No. 1 (1995): 9. ↩

-

Avraham Biran and Joseph Naveh, “The Tel Dan Inscription: A New Fragment,” Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 45, No. 1 (1995): 9. ↩

-

Avraham Biran and Joseph Naveh, “The Tel Dan Inscription: A New Fragment,” Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 45, No. 1 (1995): 9. ↩

-

Christopher A. Rollston, “Epigraphy: Writing Culture in the Iron Age Levant”, in The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Ancient Israel, ed. Susan Niditch (2016) , 135. ↩

-

Avraham Biran and Joseph Naveh, “The Tel Dan Inscription: A New Fragment,” Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 45, No. 1 (1995): 17. ↩

-

James Bennett Pritchard, ed., The Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament , 3rd ed. with Supplement. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 280. ↩

-

Philip R. Davies, “‘House of David’ Built on Sand: The Sins of the Biblical Maximizers,” Biblical Archaeology Review (July/August), Vol. 20, No.4 (1994): 55. ↩

-

Baruch Halpern, “The Stela from Dan: Epigraphic and Historical Considerations,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (November), no. 296 (1994): 63. ↩

-

Carl S. Ehrlich, “The Bytdwd-Inscription and Israelite Historiography: Taking Stock after Half a Decade of Research,” in The World of the Aramaeans II: Studies in History and Archaeology in Honour of Paul-Eugène Dion, ed. P. M. Michèle Daviau, John W. Wevers, and Michael Weigl, vol. 325, Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series (Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001), 65. ↩

-

Avraham Biran and Joseph Naveh, “The Tel Dan Inscription: A New Fragment,” Israel Exploration Journal, Vol. 45, No. 1 (1995): 18. ↩

-

Ralph W. Klein, 2 Chronicles: A Commentary, ed. Paul D. Hanson, Hermeneia—A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2012), 316. ↩

-

John J. Collins, Introduction to the Hebrew Bible and Deutero-Canonical Books, Third Edition. (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2018), 188. ↩

-

William M. Schniedewind, “Tel Dan Stela: New Light on Aramaic and Jehu’s Revolt,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (May), no. 302 (1996): 85. ↩

-

Matthew Suriano, “The Apology of Hazael: A Literary and Historical Analysis of the Tel Dan Inscription,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies (July), Vol. 66, No. 3 (2007): 171. ↩

-

Matthew Suriano, “The Apology of Hazael: A Literary and Historical Analysis of the Tel Dan Inscription,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies (July), Vol. 66, No. 3 (2007): 172. ↩

-

William M. Schniedewind, “Tel Dan Stela: New Light on Aramaic and Jehu’s Revolt,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (May), no. 302 (1996): 85. ↩

-

John J. Collins, Introduction to the Hebrew Bible and Deutero-Canonical Books, Third Edition. (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2018), 174–175. ↩

-

John J. Collins, Introduction to the Hebrew Bible and Deutero-Canonical Books, Third Edition. (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2018), 188. ↩

-

John J. Collins, Introduction to the Hebrew Bible and Deutero-Canonical Books, Third Edition. (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2018), 188. ↩

-

John J. Collins, Introduction to the Hebrew Bible and Deutero-Canonical Books, Third Edition. (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2018), 491. ↩

-

John J. Collins, Introduction to the Hebrew Bible and Deutero-Canonical Books, Third Edition. (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2018), 491. ↩

-

David Rothstein, “1 Chronicles: Introduction and Annotations (דברי הימים א),” in The Jewish Study Bible, ed. Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 1716. ↩

-

Ralph W. Klein, 2 Chronicles: A Commentary, ed. Paul D. Hanson, Hermeneia—A Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2012), 315. ↩