Gerasa, Gadara, Gergesa – from where did the pigs stampede?

A friend recently asked about the geographical problem of Mark 5 so I thought I’d write up some thoughts on the topic.

The narrative in question is the healing of Legion. Jesus is in Capernaum, he gets on a boat, sails across the Sea of Galilee, ends up in a storm, and calms the water. When they arrive on the shore he gets out and is met by two demoniacs/a guy called Legion. After Jesus heals him/them, the demons are sent into a herd of pigs. These demon-possessed pigs then run headlong into the lake and, presumably, drown. It’s fair to say this is one of the weirder gospel narratives.

The healing of Legion is narrated in all three synoptic gospels; they all begin by describing where the event took place:

Matthew 8:28 “When he came to the other side, to the country of the Gadarenes, two demoniacs coming out of the tombs met him.”1

Mark 5:1 “They came to the other side of the sea, to the country of the Gerasenes.”

Luke 8:26 “Then they arrived at the country of the Gerasenes, which is opposite Galilee.”

OK. First up: they don’t agree. Mark and Luke locate the event in “the country of the Gerasenes”; Matthew in “the country of the Gadarenes” – that’s the geographical problem we’re going to look at in this post.

These differences caused copyists of the gospels to perform no end of monkey-business with the sentence – there are 3 variants for each of the synoptic gospels.2 We’re looking at a genuine problem that was recognised very early.

If we accept Marcan Priority (which we do around here) then we’ve got Mark writing “country of the Gerasenes”, Luke following him faithfully, but Matthew deliberately changing “Gerasenes” to “Gadarenes” in his version of events. Why would Matthew do that?

Gerasa, one of the cities of Decapolis and the capital of the country of the Gerasenes, lay around 37 miles/60 kilometres away from the Sea of Galilee in what is today the city of Jerash in Jordan.3 The country of the Gerasenes did not reach the Sea of Galilee (an important point that we’ll get to in a bit).

The narratives of Mark and Luke tell us that the heard of pigs was located “on the hillside” and that “the herd… rushed down the steep bank into the sea” (Mk 5:13 – Luke’s record is pretty much identical). If you know the geography of the Sea of Galilee at all, it’s almost entirely surrounded by hills, some of them pretty steep. Interpreting the reference to “the hillside” as anywhere but the steep banks that encircle the lake is geographically problematic: the record describes a pretty short run for the pigs – their stampede was quickly over.

This is a difficulty for Mark’s account – the pigs would have had to trot many miles from the country of the Gerasenes before they even reached the hillside that overlooks the lake, never mind actually get to the lake itself. And that doesn’t fit the description we’re given of the stampede at all.

Matthew, using Mark as a source for his own gospel, appears to have been aware of this geographic difficulty. To deal with it he changed “country of the Gerasenes” to “country of the Gadarenes”:

Matthew 8:28 “When he came to the other side, to the country of the Gadarenes, two demoniacs coming out of the tombs met him.”

Why would he do that? Why swap out one territory for another?

The city of Decapolis whose territory stood between the country of the Gerasenes and the Sea of Galilee was Gadara, modern Um-Qais in Jordan. Gadara was the capital of Matthew’s “country of the Gadarenes”. Josephus explains that the country of the Gadarenes reached the shore of the lake:

“the villages of the Gadarenes… happened to lie on the frontier between Tiberias and the territory of the Scythopolitans.”4

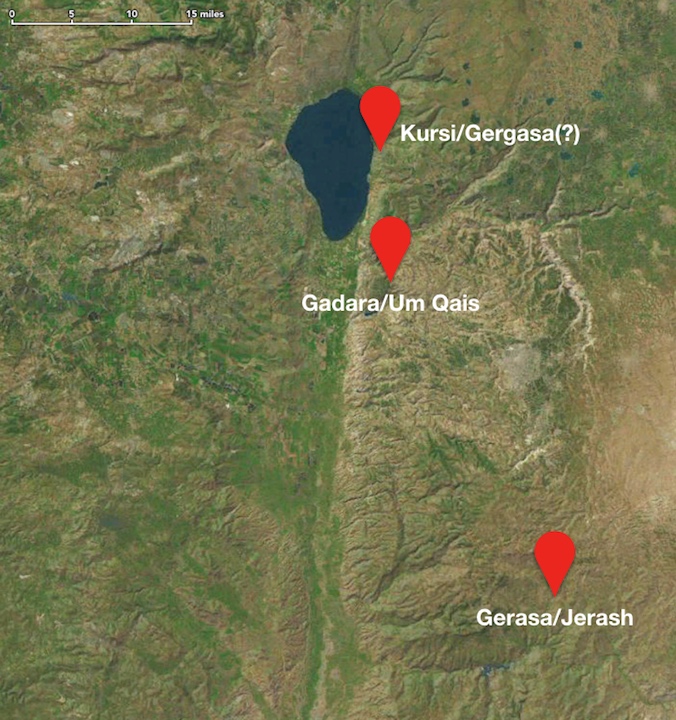

So at least that part of the story adds up – the pigs could have run into the lake from Gadara’s territory. However, check out this map:

Gadara itself or anywhere relatively close to it is still quite a distance – a number of miles/kilometres. The pigs would still have had to have been long distance runners – not the picture painted for us in Mark or Luke where the herd is on the hillside close to the water.

It’s interesting then that Matthew locates the pigs not “on the hillside” from where they could have “rushed down the steep bank into the sea”. Here’s where Matthew locates the pigs:

Mt 8:30 Now a large herd of swine was feeding at some distance from them.

Let’s be clear: I know zero greek. Like, not even the alphabet. So, I’m kinda dependent on lexicons to tell me what’s what. The “at some distance” is a bit fluffy in the english – it could mean anywhere from “not far” to “miles away”. So, all a layman like me who wants to avoid “exegeting the english” can do is trust good scholarship:

- BDAG: “be far away from someone or something”5

- Louw & Nida: “a position at a relatively great distance from another position—‘far, at a distance, some distance away, far away.’”6

It’s comforting to know that Luz translates it “But far off from them a large herd of pigs was feeding.”7 On the other hand, Newman and Stine make the astute observation that “It seems that ‘at some distance’ does not indicate a great distance, since the pigs can be seen.”8

All I’m able to say with any confidence is that Matthew felt compelled to change the location of the pigs. He could have followed Mark, but he chose to do something else.9 It seems reasonable to this layman to suggest that maybe Matthew relocated the herd because he knew enough of the geography to say that if this event took place in the country of the Gadarenes the herd couldn’t be both on a hillside and close to the shore – Gadara was around 5 or 6 miles away from the shore, and the hills that lead from Gadara to the lake are very close to Gadara and a number of miles from the lake.

So, Matthew is aware that on the face of it Mark’s account doesn’t work. He therefore took it upon himself to change the geographical details to make them more realistic. To get any further with working out where the event took place (if it took place at all) we can turn to church history.

Eusebius of Caesarea (260–313 CE10) in his Onomasticon (basically a long list of place names with explanations of their location), not content with his available options of Gerasa and Gadara Eusebius decided to add a third candidate:

Eusebius, Onomasticon, 74: Gergesa – There the Lord healed the demoniacs. Now a village is pointed out beside Lake Tiberias, into which the swine rushed down headlong.11

Gergasa, it has been suggested12, is a transliteration of Kursi, located half way up the eastern shore of the Sea of Galilee.

Scholarship seems to be split on whether Gergasa/Kursi is a viable option or not:

- “…a site named Khersa (or Kursi) among the cliffs overlooking the lake—the “traditional” site, but with little to argue in its favor.13

- “The “Gerasa” of Mark 5:1 was probably Kursi/Gergesa”14

But, what’s the historical value of Eusebius’ claim? After all it’s not far off 300 years after the events.

Well, it seems Eusebius didn’t arrive at his “Gergesa” idea alone; it appears he may have just been following Origen’s (185-253 CE) commentary on John where we read:

Origen, John. 6.211. “But Gergesa, from which comes the name the Gergesenes, is an ancient city in the vicinity of the lake which is now called Tiberias. There is a cliff lying beside this lake from which they point out the swine were cast down by the demons.”15

That’s a pretty early source, and he’s appealing to an earlier tradition (“from which they point out…”) but whether the entry really reflects ancient tradition is hard to know.

One thing’s for sure: Gergasa, if it can be equated with Kursi, is “the most geographically plausible”16 reading. Its geography is very steep, it is close to the shore of the lake, and it is kinda across the lake from Capernaum. Geographically it’s certainly a better fit than Gerasa or Gadara.

When it comes down to it we really have no idea where the event the narratives are based on took place. It’s just one of those things. We’ll probably never find out what the real deal is, but, as usual with these things, that’s only a problem if we subscribe to the patently false doctrine of inerrancy.17

So…how did this problem arise? Was Mark’s knowledge of the Decapolis shaky? Did he just take a stab at a location that seemed possible based on what he’d heard somewhere? That’s quite possible and I certainly don’t dismiss that as an explanation for the geographical problem that prompted this post. However, I’m not alone in thinking that this isn’t the best explanation.1819 What I find a more credible suggestion is that given by Marcus in his commentary on Mark:

Although “Gerasa” is difficult geographically, it is appropriate symbolically, since the Hebrew root grš means “to banish” and is a common term for exorcism.20

If Marcus is right then here’s an oversimplified explanation of what may have happened:

Mark, wanting to make a theological point, locates the event in a place whose name is associated with casting out demons – the language, as Marcus points out, does kinda support this.21 This strengthens the exorcism theme of the pericope– seems legit. A few years later, Matthew, using Mark as a source for his own gospel, either misses Mark’s theological point or wants to achieve something else with his text and attempts to “correct” the event’s location. He deals with a remaining issue by locating the herd “some distance away” rather than on the hillside next to the lake. Around 150 years later Origen comes along, and, knowing that Matthew’s attempted fix isn’t watertight, relocates the event to Gergasa based on what is probably an ancient tradition.

That’s just this layman’s 2 cents.

Conclusion: we just don’t know where this event is supposed to have taken place.

But one thing’s for sure: wherever the event happened it was a waste of good bacon.

Footnotes

-

All scripture quoted from The Holy Bible: New Revised Standard Version (Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1989) ↩

-

If you want to get into the detail see Bruce Manning Metzger, United Bible Societies, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, Second Edition a Companion Volume to the United Bible Societies’ Greek New Testament (4th Rev. Ed.) (London; New York: United Bible Societies, 1994), 18, 72, 121. ↩

-

“The name “Gerasenes” is to be associated with the modern city of Jerash, located in Transjordan, 22 miles N of Amman.” John McRay, “Gerasenes,” ed. David Noel Freedman, The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 991. ↩

-

Flavius Josephus and Steve Mason, Flavius Josephus: Life of Josephus (Boston; Leiden: Brill, 2003), 47. ↩

-

William Arndt et al., A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 612. ↩

-

Johannes P. Louw and Eugene Albert Nida, Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament: Based on Semantic Domains (New York: United Bible Societies, 1996), 716. ↩

-

Ulrich Luz, Matthew: A Commentary, ed. Helmut Koester, Hermeneia—a Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible (Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg, 2001), 23. ↩

-

Barclay Moon Newman and Philip C. Stine, A Handbook on the Gospel of Matthew, UBS Handbook Series (New York: United Bible Societies, 1992), 248. ↩

-

Which is why I don’t buy McRay’s argument, “The problem is in the similarity of spelling in Greek. Ancient scribes probably heard or saw one name in the process of copying a manuscript and thought they heard another.” John R. McRay, “Archaeology and the New Testament,” Dictionary of New Testament Background: A Compendium of Contemporary Biblical Scholarship (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000), 97. ↩

-

Glenn F. Chesnut, “Eusebius of Caesarea (Person),” ed. David Noel Freedman, The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 673. ↩

-

Freeman-Grenville, Chapman, and Taylor, The Onomasticon by Eusebius of Caesarea (Carta Jerusalem, 2003), 45. ↩

-

Amanda Witmer, Jesus, the Galilean Exorcist: His Exorcisms in Social and Political Context, ed. Robert L. Webb and Mark Allan Powell, vol. 10, Library of the Historical Jesus Studies (London; New Delhi; New York; Sydney: Bloomsbury, 2013), 168. ↩

-

Donald A. Hagner, Matthew 1-13, vol. 33A, Word Biblical Commentary (Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1998), 226. ↩

-

James R. Edwards, The Gospel according to Mark, The Pillar New Testament Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI; Leicester, England: Eerdmans; Apollos, 2002), 154. ↩

-

Origen, John. 6.211. Commentary on the Gospel according to John – Books 1-10, Ed. Thomas P. Halton, trans. Ronald E. Heine, Vol. 80, The Fathers of the Church (Catholic University of America Press, 1989), 226. ↩

-

Joel Marcus, Mark 1–8: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, vol. 27, Anchor Yale Bible (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2008), 342. ↩

-

For those who subscribe to inerrancy, get over yourselves and actually read the text. The Bible is way more interesting than inerrancy would have you believe. ↩

-

“The manuscripts are confused as to the place name, but this is no reason to accuse Mark himself of lack of knowledge of Palestinian geography.” R. Alan Cole, Mark: An Introduction and Commentary, vol. 2, Tyndale New Testament Commentaries (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1989), 158. ↩

-

Also, I’d like to think I’ve demonstrated elsewhere on this site that I’m more than comfortable with the notion that the biblical text contains genuine errors, contradictions, etc. I just think that in this case there’s a better explanation. ↩

-

Joel Marcus, Mark 1–8: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, vol. 27, Anchor Yale Bible (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2008), 342. ↩

-

Ludwig Koehler et al., The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1994–2000), 204. ↩