Ezer, Elead, and Exodus

The first few chapters of Chronicles are a real slog to read through. Name after name; genealogy after genealogy; tongue-twister after tongue-twister. If we force ourselves to read the chapters our eyes quickly glaze over and we tune out. But if we do that, we’ll miss out. No, seriously. In this instance we’ll see the Chronicler subtly remove both Israel’s sojourn in Egypt and the Exodus from their history.

In 1 Chronicles 7:20-29 we read the genealogy of Ephraim. It starts off in the usual style:

1 Ch 7:20–21 The sons of Ephraim: Shuthelah, and Bered his son, Tahath his son, Eleadah his son, Tahath his son, Zabad his son, Shuthelah his son, and Ezer and Elead.1

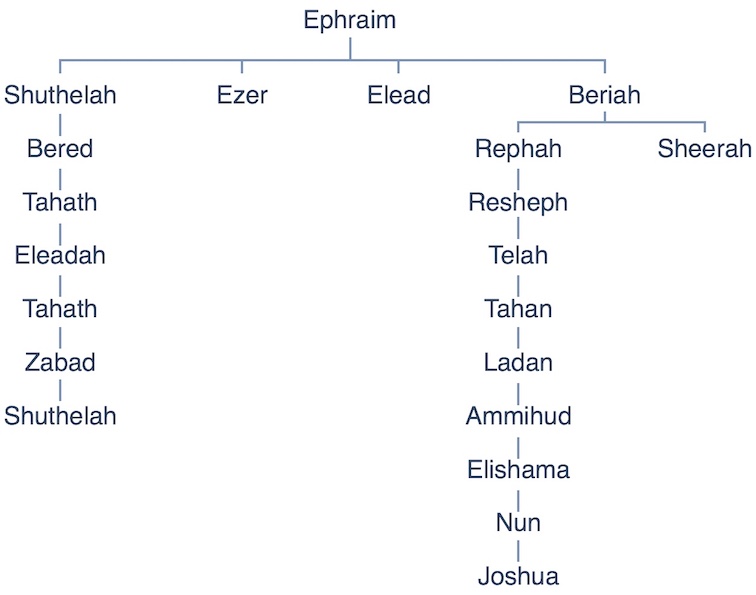

Interestingly, Ezer and Elead don’t follow the usual “XXXXX his son” pattern. If we continue reading we find out why: they’re actually the 2nd and 3rd of Ephraim’s sons; Shuthelah being the 1st, and Beriah (v23) being the 4th. When you put it all together, you get this family tree:

So far, so boring.

A short story

If we continue reading from where we stopped halfway through v21 we come across this tale:

1 Ch 7:21b–23 Now the people of Gath, who were born in the land, killed them, because they came down to raid their cattle. And their father Ephraim mourned many days, and his brothers came to comfort him. Ephraim went in to his wife, and she conceived and bore a son; and he named him Beriah, because disaster had befallen his house.

Tragedy had come to Ephraim: his sons Ezer and Elead were killed. Who killed them? The people of Gath. Why? Because they caught Ezer and Elead coming down to rustle their cattle. The ancient Near East was a brutal place.

Naturally, Ephraim went into a period of mourning for his two sons which lasted “many days”. He was joined by his brothers who came to comfort him.

Ephraim then went on to have another son, Beriah, so named “because disaster had befallen his house”; ‘Beriah’ meaning calamity or disaster.2

Just before getting back to the genealogical details, the short story concludes by telling us that Beriah had a daughter, Sheerah (v24), and that she was credited with building “both Lower and Upper Beth-horon”.

And with that, we’re back to the tedium of unrecognisable names – with one exception: the genealogy ends in v27 with Joshua the son of Nun, of Canaanite Conquest fame.

Why is any of this interesting? It turns out that the short story contradicts everything we are told elsewhere about Israel in Egypt, the Exodus, and Israel’s conquest of Canaan.

The main narrative

Let’s just remind ourselves of the Hebrew Bible’s main narrative…

Ephraim, the head of our genealogy, was born to Joseph and Asenath in Egypt; he had one brother, Manasseh (Ge 41:50–52, 46:27, 48:1). Many generations later, Joshua the son of Nun came out of Egypt on the Exodus and acted as Moses’ right-hand-man (Ex 17:8–13). In the intervening period the Israelites were in Egypt (Ge 50:23, Ex 1:7). When the Israelites entered Canaan after the Exodus, Joshua on his Southern Campaign chased an Amorite coalition down the valley of Ajilon, passing by Beth-horon (Jos 10:10).

The Chronicler’s counter-narrative

Starting with Sheerah who appears only here in the Chronicles record, she is credited with building Upper and Lower Beth-horon. But, if she was in Egypt (being a descendent of Ephraim but predating the Exodus), why was she building cities in the Canaanite highlands, specifically the Ephraimite highlands3 of Canaan?

This isn’t at all what we’d expect from someone living in Goshen, hundreds of miles away from the Ephraimite hills.

What about Ezer and Elead? In which direction did they go to Gath? Down. This is quite telling. Journeys from Egypt to Canaan in the Hebrew Bible describe the direction as up from Egypt; if the journey is the reverse then the direction is down to Egypt.4

So, if they went down to Gath then they can’t have come from Egypt. If they had come from Egypt the text would say:

Now the people of Gath, who were born in the land, killed them, because they came

downup to raid their cattle.

A reading that respects the biblical language of direction to and from Egypt and also pays attention to the topography of Canaan has Ezer and Elead coming down to Gath from the nearby Canaanite highlands5, incidentally, not many miles from Beth-Horon.

Finally, who was it who came to comfort Ephraim? His brothers. Plural. This goes against scripture’s main narrative that tells us quite emphatically that Ephraim had only one brother, Manasseh.

The ramifications of all this are that 1 Chronicles 7:20-27 give us a picture of the origins of the tribe of Ephraim that don’t fit the usual story of Israelite origins. In fact, the two contradict. The Chronicler’s short story has Ephraim living in the Canaanite highlands and not Egypt, not going on any Exodus, and having no need to conquer the land – they’re already living and building in it.

So, what is the Chronicler up to?

The Chronicler’s purpose

Writing after the exile6, the Chronicler had an altogether different audience than the pre-exilic writers had. His readers were the dispirited, downtrodden, and desperate Jewish descendants of those who’d seen their land torn apart, their temple destroyed, and their families killed. They themselves had only known the life of a displaced and conquered people. The Chronicler’s job was to give his audience hope, to remind them of their glorious history, and their God-ordained monarchy. For this reason he doesn’t mention David’s rape of Bathsheba and his murder of Urijah (2 Sa 11), he ignores Solomon’s idolatry (1 Ki 11), and, most importantly, he avoids mentioning the Exodus wherever possible.

Why does the Chronicler ignore the Exodus? Because he wanted to ground the Jews in their ancestral homeland. Reminding them of the fact that they weren’t natives of it but in fact were at one time foreigners did not suit his purpose. So, the Exodus is skipped right over.

To give an example of this sort of selectivity in the very passage we’re looking at, in v27 we find mention of Joshua the son of Nun. But, instead of the Chronicler relaying what an amazing military strategist he was, or how his faith in God was exemplary, we get nothing. Just his name and ancestry. Bear in mind that this is the only mention of Joshua in both 1st and 2nd Chronicles, a supposed history of the people of Israel. Why? Because to spend time discussing the conquest would be to remind his post-exilic audience that at one time they didn’t belong in Israel. The Chronicler wanted to achieve the opposite!

Whatever source the Chronicler worked from that contained the story of Ezer and Elead, it suited his purpose well. It assisted him in providing a narrative of long and unbroken chain of Israelite presence in the land.

It’s details like this that demonstrate that the Chronicler wasn’t interested in presenting history as we today might expect him to. Instead, he had a loftier purpose, and he was more than happy to bend history to it. His purpose was to comfort a small group of people who’d suffered terribly over a number of decades. And comfort trumps dry history.

Further reading

- Is that in the Bible? - The Story of Ezer and Elead (and What It Means for the Exodus)

- The Torah.com - The Book of Chronicles and the Ephraimites that Never Went to Egypt

- Gary N. Knoppers, I Chronicles 1–9: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (vol. 12; Anchor Yale Bible; New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2008), 463–466.

- Ralph W. Klein, 1 Chronicles: A Commentary (ed. Thomas Krüger; Hermeneia—a Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible; Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2006), 231–236.

- Roddy L. Braun, 1 Chronicles (vol. 14; Word Biblical Commentary; Dallas: Word, Incorporated, 1998), 113–116.

Attribution

Featured image: Gath by אבישי טייכר is licensed under CC-BY-2.5.

Footnotes

-

All scripture quotations from New Revised Standard Version (Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1989) ↩

-

Ludwig Koehler et al., The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1994–2000), 1263–1264. ↩

-

In Joshua 16:1-3 we are told that Lower Beth-Horon marked the southern border of Ephraim’s tribal allotment ↩

-

E.g. Ge 12:10, 13:1, 26:2, 37:25, 39:1, 43:15, 46:3, Nu 20:15, Dt 10:22, Jos 24:4, 24:32, Jdg 2:1, 6:8, 6:13, 11:16, Is 30:2, 31:1, Ho 12:13 ↩

-

“The anecdote presupposes that Ephraim, his wife, and his sons and daughter were all residing in the land, more specifically in the hill country.” Gary N. Knoppers, I Chronicles 1–9: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (vol. 12; Anchor Yale Bible; New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2008), 464. ↩

-

Ralph W. Klein, 1 Chronicles: A Commentary (ed. Thomas Krüger; Hermeneia—a Critical and Historical Commentary on the Bible; Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2006), 13–16. See also Gary N. Knoppers, I Chronicles 1–9: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (vol. 12; Anchor Yale Bible; New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2008), 116–117. ↩