A visit to the Bull Site

This self-indulgent post is about how I managed to locate and visit one of the most obscure and off-the-beaten-track locations in the West Bank related to early Israelite religion. You’ve probably got better things to do with your time than read through it, but you know… /shrug.

Back in 2011 I came across a small bronze bull statuette in the Israel Museum. The explanatory sign next to it read,

Found at an open-air ritual site in the Israelite heartland, this fine statuette brings to mind the golden calf of the Exodus story… This was quite a few years ago before my interest in Israelite origins and early Israelite religion really started so I didn’t take a great deal of notice.

This was quite a few years ago before my interest in Israelite origins and early Israelite religion really started so I didn’t take a great deal of notice.

In 2013 I was back at the museum with my wife and saw the piece again. “Open air ritual site, huh. We should see if we can find it,” I suggested to her. “Sure”, she responded. As maybe she’d expected, I promptly forgot all about it as soon as I got to the next interesting display cabinet in the museum.

Recently while preparing for a trip to Israel with my wife and kids I remembered my plans to visit the site and decided to include it on our itinerary. Over the past few years I’d been reading around the topics of Israelite origins and early Israelite religion and so had familiarised myself with the background to the site. However, actually locating it would require getting into significantly more detail than I’d gone into thus far.

Not much help

Very little of what I’d read to that point offered much more than “a site in the hill country of Ephraim”1, “in the Samarian Hills”2, or “four miles east of Dothan”3. Clearly, finding this place wasn’t going to be easy.

Thankfully, a number of bibliographies pointed to the original paper in BASOR by Amihai Mazar entitled “The “Bull Site”: An Iron Age I Open Cult Place” published in 1982 in BASOR.

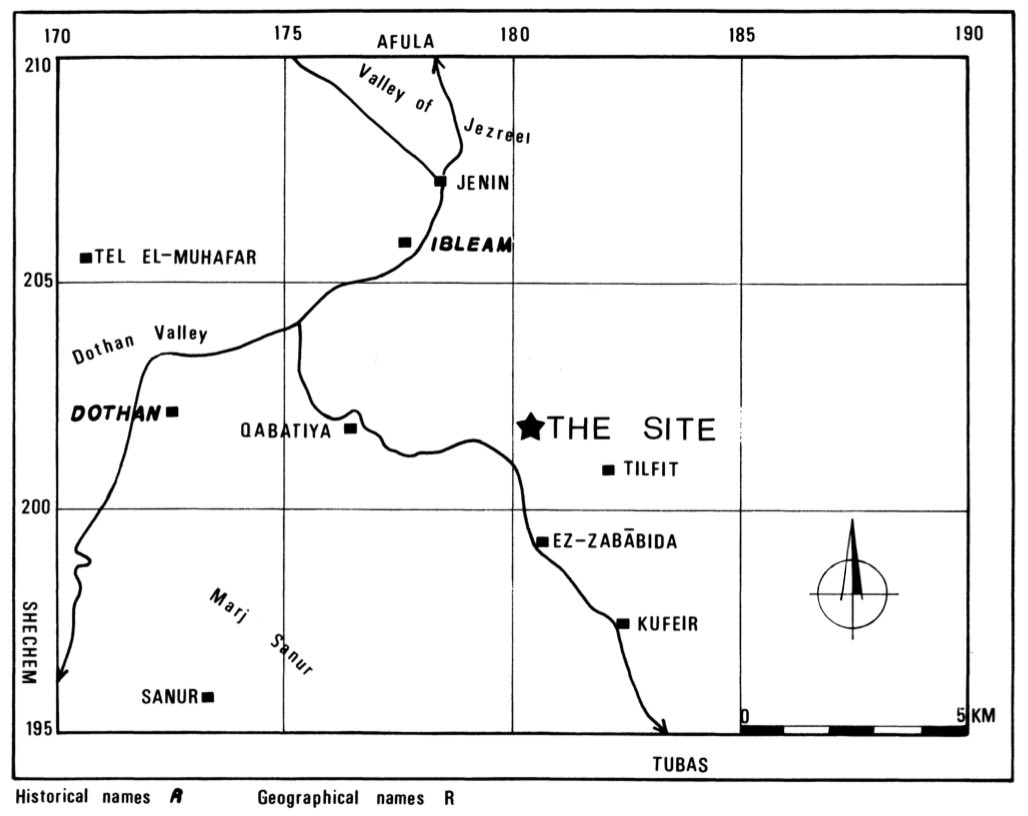

The article contains a map, which, to the casual reader is probably enough to satisfy any desire to know the site’s location. Here it is:

As pretty as the map may be, it’s still pretty useless when it comes to actually making my way to the place. Are there coordinates or something? Anything I could use to find the place on Google Maps? Once again, the article promised much, but served up little:

The site (1807 x 2016; 7186 x 5844 in the U. T. M. grid) is located on a summit of a ridge in the northern part of the Samaria hills.4

Wut? The “UTM Grid”? What on earth is that? I googled around but didn’t find anything that would reliably convert something from UTM grid notation into ordinary coordinates that Google Maps (or any other digital mapping tool) could understand. (I’ve since been given a set of original maps from the Survey of Palestine, and also found a digital version of those maps here, and now know what I’m looking at with these coords :) )

Getting closer

I’d heard through the grapevine that in the following year Mazar had published another article on the same topic aimed at a lay readership in BAR.5 So, I finally broke down and got myself a subscription. And I’m glad I did – the relevant article contained useful information:

I vividly recall my first visit to the site. It is located on the summit of a high ridge. In the distance I could see the most important ridges in northern Palestine. There to the north were Mount Tabor and Mount Meiron; to the west was Mount Carmel; to the northeast was Mount Gilboa; and to the south was Jebel Tamun.6

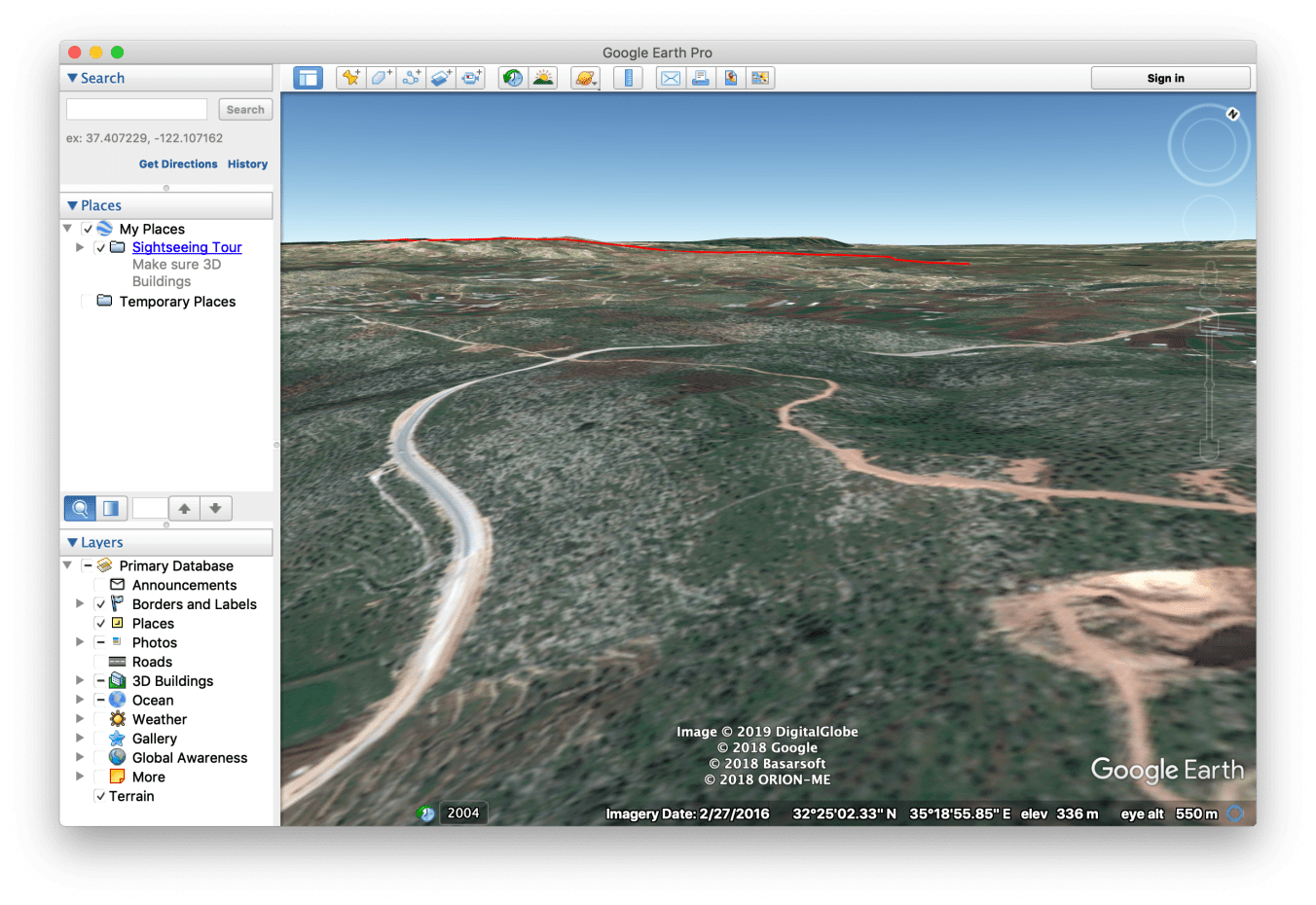

Great! A high ridge (named Dharaht et-Tawileh) from which a bunch of notable hills can be seen. I knew where those hills were so I broke out Google Earth, went to the general location (based on the map above), and found somewhere I could spin around and see the relevant peaks. Naturally, I wasn’t able to pin it down to a specific ridge but I felt I was getting close.

Great! A high ridge (named Dharaht et-Tawileh) from which a bunch of notable hills can be seen. I knew where those hills were so I broke out Google Earth, went to the general location (based on the map above), and found somewhere I could spin around and see the relevant peaks. Naturally, I wasn’t able to pin it down to a specific ridge but I felt I was getting close.

It was now a matter of figuring out which ridge was the one I was after. In his 1982 paper Mazar described its location:

“The ridge is bounded on the south by a long east-west valley, in which the village of Zababda is situated…”7

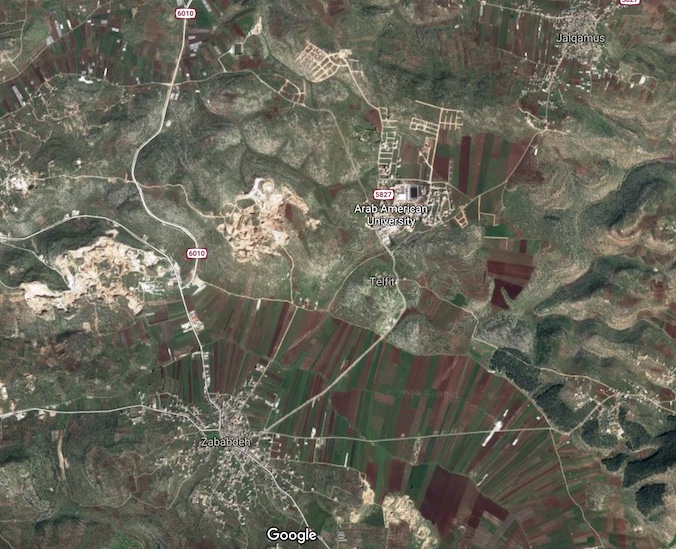

Cool. Here’s that valley:

Mazar continues,

…the site is situated high above the valley and does not overlook the valley itself.8

That was also helpful – I knew the hilltop of the Bull Site ridge was not directly north of the east-west valley but had to have its view blocked by the ridge directly north of the valley. I was now homing in on it…

At this point I needed photos. I wanted pictures more up to date and useful than the ones in Mazar’s articles and began looking through Instagram. Because there aren’t many photos tagged #zababdeh (the closest town with a view of the ridge) it wasn’t long before I came across this gallery. The 6th image particularly matched the terrain in Mazar’s articles.

As close as I’m going to get…

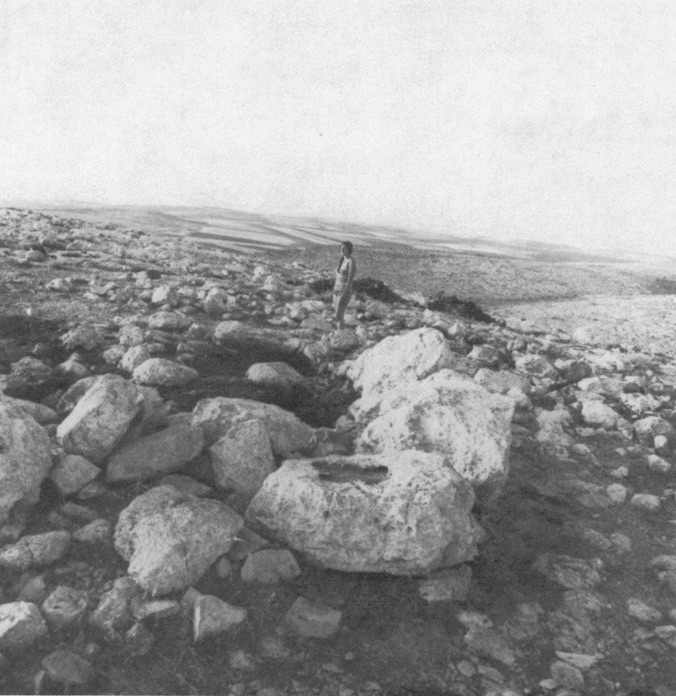

Still, the most useful picture I ended up with was this one from Mazar’s first paper:

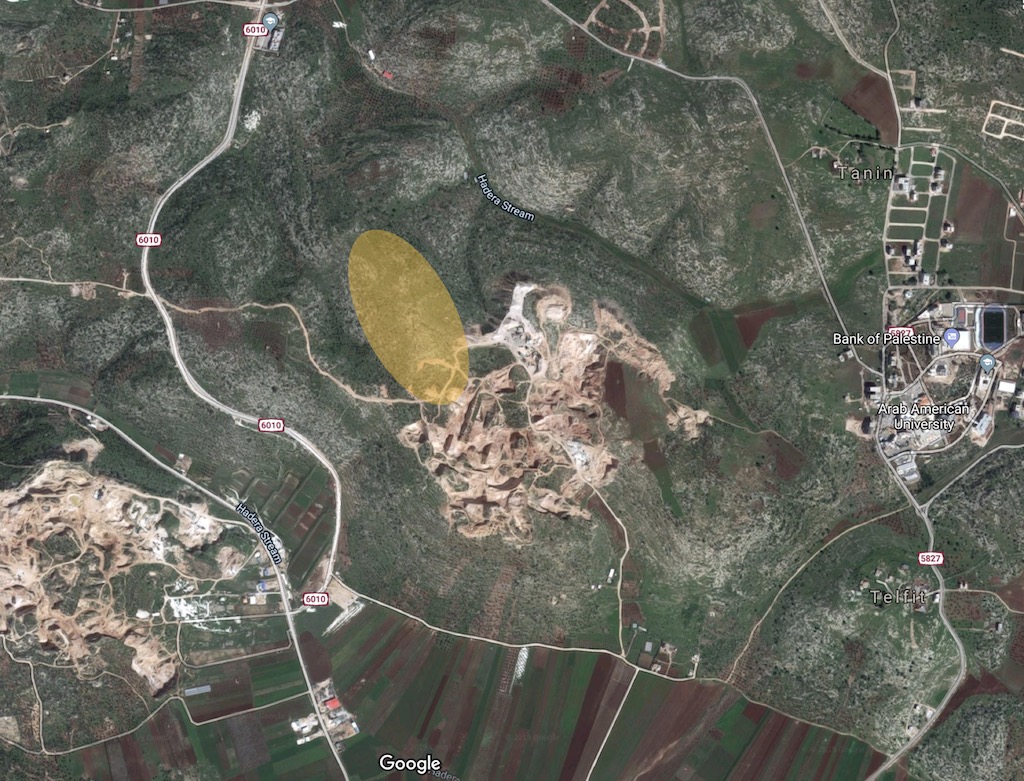

With the above as input I cruised around the ridges directly north of Zababdeh (as per the map above) and after a while I finally located the ridge of Dharaht et-Tawileh. I was 95% sure it was this one on Google Maps:

The very highest point of that ridge seemed very close to the quarry. Zooming in, Google Maps 3D and Google Earth would have me believe the ridge peak is here:

I figured, based on that, that the best way to get there would be the dirt track to the west of the peak. Here was my plan:

The only flaw is that if the quarry was illegal (and I can’t find a single thing about it anywhere online so it’s likely to be) I probably wouldn’t be made to feel welcome. Well, there was only one way to find out… drive there and see.

The day arrives

On May 20th, 2019, after two weeks of touring around Israel with my wife and two boys, I woke up in Ein Gev on the eastern shore of the Sea of Galilee. We packed the car, woke the kids, had breakfast, and set off for the Bull Site.

We drove south to Beth-Shean, turned west into the Jezreel Valley, keeping Mount Gilboa to our left. When we reached highway 60 we turned south onto what is known as the “Way of the Patriarchs” – the route that winds its way through many well known biblical sites (Samaria, Bethel, Shiloh, Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Hebron to name just a few). To avoid Jenin we almost immediately turned off onto the 6010 and drove south. We followed it almost to the end where we turned onto the dirt track shown on the map above. Here’s the terrain:

Very pretty. About 30 seconds in I caught up with a large truck probably heading to the quarry to pick up some rock or something.

The driver stopped, blocking the road. He hopped out of the car and used the accepted international hand gesture for “what on earth are you up to?” I responded in the finest tourist English, pointing at the top of the hill, “Salamaleikum, I’m going up there,” and reached out to shake his hand. He appeared quite confused, but seemed satisfied. We shook hands, he hopped back into his truck, and I followed him to the top of the hill.

As the dirt track reached the top of the hill we turned off it as per the plan and parked the car. I grabbed my camera and plastic toy cow I’d bought for the occasion and wandered the short distance to the top of the hill. Lo and behold…

THE BULL SITE.

I ACTUALLY FOUND THE ACTUAL BULL SITE.

Expecting to be escorted away by security at any moment I wanted to memorialise the event in the only way a millennial knows how – a selfie:

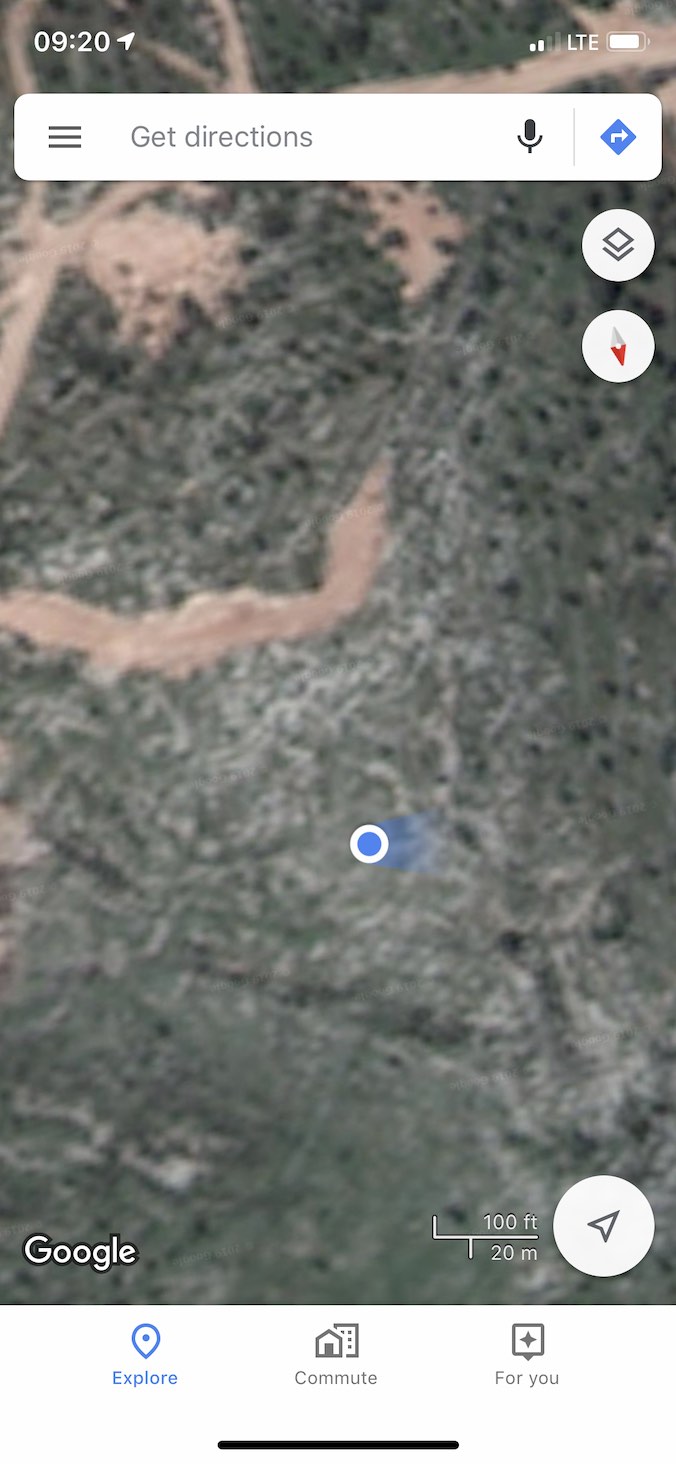

The selfie having been taken it was time to confirm my location. I stood in the centre of the Bull Site enclosure, let the GPS on my iPhone settle, and took a screenshot. In my wild excitement I forgot to set it to have north pointing upwards.

Ah well, what’s important is this: I’d got it right. All those hours hunting down and reading articles, poring over maps, checking, double checking, and triple checking everything had paid off. The site was exactly where my research said it would be. That’s quite a win for this unqualified layman.

Having patted myself on the head and beaten my chest gorilla-style, I thought I’d better get on with gathering more serious footage.

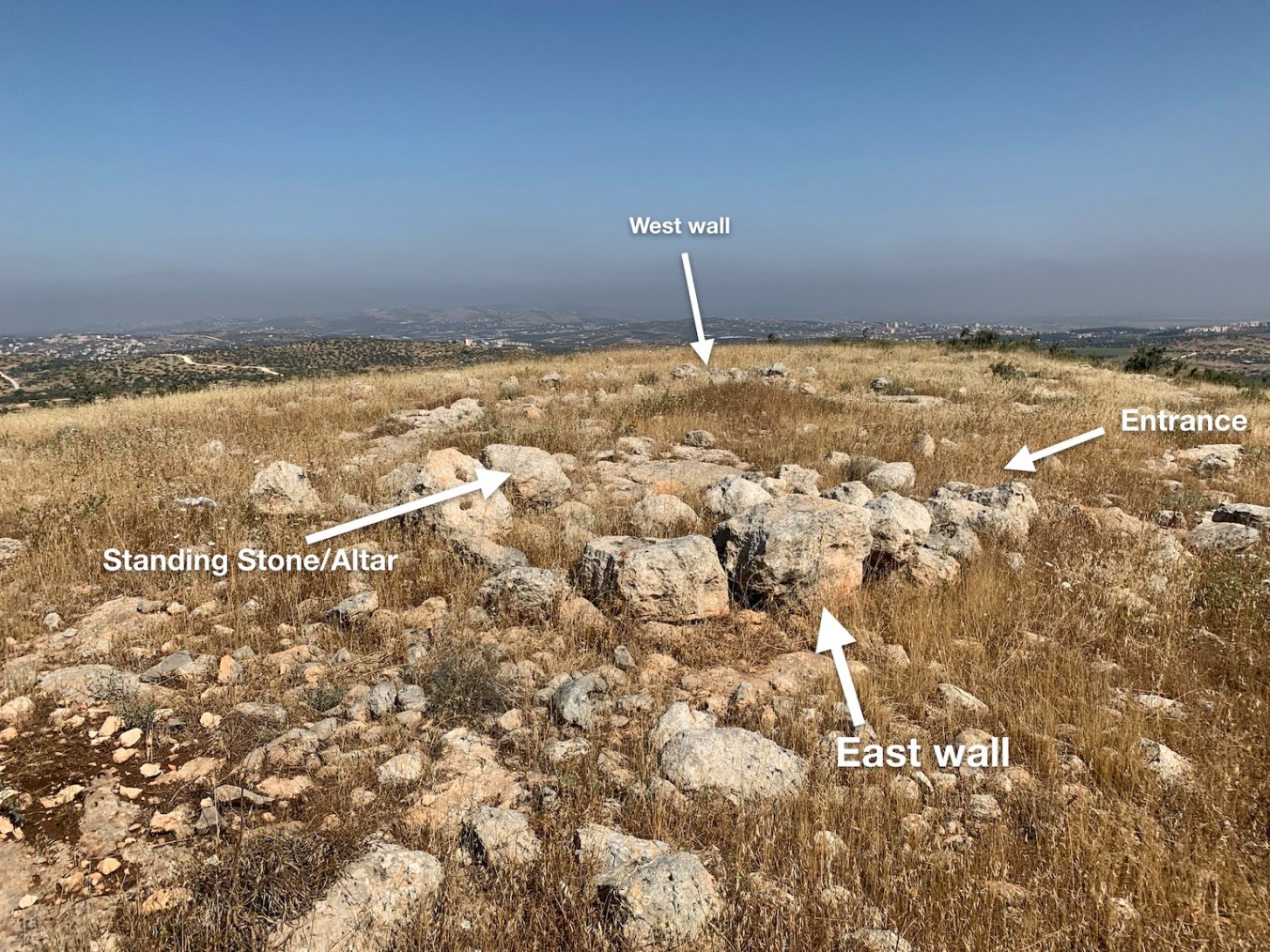

I spent the next hour and a half wandering around getting loads of video and a ton of photos. Here’s a small sample:

I also took a fair bit of video. Here are a couple that should give you an idea of the place:

Personal reflection on reaching the site.

A two minute wander into the bull site starting from the south east, entering the enclosure through its ancient entrance, taking a look at the standing stone/altar, and then panning 360 degrees finishing at the standing stone/altar again.

There’s more over at the Biblical Historical Context youtube channel.

Well, there we go. I was pretty pleased with myself. I got there, and managed to get what I think are the only colour photographs of the site since Mazar’s 1983 paper. I’m also pretty sure the videos above are the only ones ever taken. I’d love to be corrected on either point, so if you know anything please drop me a line on the facebook page or on twitter.

Postscript

When I was reading up on the site I was quite surprised to find that it didn’t have a wikipedia page. So I wrote one. You’re welcome: The Bull Site.

Another point… In reading one of the papers relevant to the site I found scholars pontificating about the site based on the few, small, grainy, black and white photos in Mazar’s 1982 paper, without having visited it. Here’s an example:

…the proposal by Wenning and Zenger, that Tawileh was used as a threshing floor in addition to a cult place, seems unlikely from the photos published in Mazar’s article.9

Err… “seems unlikely from the photos“!?

Final point: I’m working on a YouTube video that’ll explain the Bull Site (from an uneducated layman’s perspective). Given I don’t know iMovie this may take some time…

Footnotes

-

Mark S. Smith, The Early History of God: Yahweh and the Other Deities in Ancient Israel (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.; Dearborn, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company; Dove Booksellers, 2002), 83. ↩

-

Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible 10,000-586 B.C.E. (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 1990), 353. ↩

-

Richard S. Hess, Israelite Religions: An Archaeological and Biblical Survey (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2007), 236. ↩

-

Amihai Mazar, “The “Bull Site”: An Iron Age I Open Cult Place,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (Summer), no. 247 (1982): 32. ↩

-

Amihai Mazar, “Bronze Bull Found in Israelite ‘High Place’ from the Time of the Judges,” Biblical Archaeology Review 9:5, September/October 1983. ↩

-

Amihai Mazar, “Bronze Bull Found in Israelite ‘High Place’ from the Time of the Judges,” Biblical Archaeology Review 9:5, September/October 1983. ↩

-

Op. cit., Mazar 1982, 32. ↩

-

Op. cit., Mazar 1982, 32. ↩

-

Gösta W. Ahlström, “The Bull Figurine from Dhahrat et-Tawileh,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (Summer), no. 280 (1990): 78. ↩