From Cornwall to Canaan: Locating the Southern Levant’s Late Bronze Age Source of Tin

Preface

I try to make at least one trip to the lands of the Bible every year. In 2020 I’ve been prevented from doing so due to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Not willing to allow the travel ban to make me break with my tradition, I decided to find some tenuous link between England, where I currently live, to Israel, where I’d been prevented from visiting. And, dear reader, tenuous link I found.

So, on a fine weekend in September 2020 I dragged my long suffering wife and kids on a socially-distanced trip to see ancient tin mines, burial mounds, and Late Bronze shipwreck sites in Cornwall and Devon. I don’t know about them but I had a whale of a time :)

Bronze in the Ancient Near East

The Bronze Age, named for the dark brown metal alloy used in the period, began in the ancient Near East around 3300 BCE and ended around 1200 BCE.1

Perhaps surprisingly, for the first 1000 years of the Bronze Age, bronze was unknown. It was only in around 2300 BCE that metallurgists in the region began to alloy copper with 10-15% tin to produce bronze2, and it took another 300 years for this practice to become widespread. Bronze only replaced copper in tool making and weaponry in around 2000 BCE.3

Bronze was a revolutionary technology. It was much stronger than copper, and such was its strength and utility that it was finally replaced by iron only one thousand years later, in around 1000 BCE.4

The strategic importance of tin

Bronze could not be produced without tin. Tin, therefore, was of great importance to the continuation of civilization as it was. Bell explains that,

The trade in the raw materials for bronze manufacture was unquestionably strategic as bronze weapons were essential for maintaining the balance of power between the competing empires.5

She continues with an analogy to our own times to emphasise the point:

the strategic importance of tin in the LBA, being far scarcer in nature than copper, was probably not far different from that of crude oil today. Tin supply was absolutely vital for the maintenance of the status quo in Late Bronze Age society as bronze tools had become widely used by this time in all manner of trades. Furthermore, the availability of enough tin to produce what I like to call weapons grade bronze must have exercised the minds of the Great King in Hattusa and the Pharaoh in Thebes in the same way that supplying gasoline to the American SUV driver at reasonable cost preoccupies an American President today!6

Given the vast array of bronze artefacts that have been found all over the southern Levant, there must have been loads of tin floating around the place.7 Scripture too is littered with mentions of bronze. Whatever we may think of the historicity of the relevant narratives, it was assumed by the biblical writers that bronze was commonly available in the period of Israel’s early history, and long before.

At Sinai the Israelites were said to have contributed “708 talents and 2400 shekels” of bronze for the construction of the Tabernacle (Ex 38:29-31) – that’s 2,400kg, or 5310 pounds.9 Moses is famously said to have made a bronze serpent (Nu 21:9). When Jericho fell to Joshua’s army the Israelites were said to have collected bronze as part of the loot (Jos 6:24). The Philistines restrained Samson with bronze shackles (Jdg 16:21). Goliath’s helmet, mail coat, greaves, and spear were all said to have been made of bronze (1 Sa 17:5-6). At the entrance of Solomon’s Temple stood two bronze pillars (1 Ki 7:15) created by Hiram, the highly skilled Tyrian bronze worker (1 Ki 7:13-14). Examples could be multiplied.

Tin on the other hand hardly gets any scriptural airtime. The metal is mentioned three times in Ezekiel; once in the Lament for Tyre as being something traded by Tarshish10; twice it’s used figuratively of the house of Israel as one of many metals that when smelted produce dross. Other than those instances in Ezekiel, tin is only mentioned in the list of loot taken by the Israelites when they fought the Midianites before entering the promised land (Nu 31:21-22).11

Also, unlike copper, tin was not mined in the southern Levant or anywhere near it:

Sources of tin throughout the world are scarce, and apart from three sources identified in the eastern desert of Egypt (for which there is no evidence of exploitation in antiquity), there are no known sources of tin anywhere in the Aegean, Eastern Mediterranean, or Near East. Thus the spread of tin-bronze as the predominant metal in the ancient Near East beginning in the third millennium BCE implies the existence of some type of long-distance trade.12

That the Hebrew word for tin, בְּדִיל, is a Sanskrit loan word only underscores the foreign nature of the metal.13

So, we’ve got an interesting problem: based on the huge amount of bronze that was in use, evidently there was loads of tin available in the ancient Near East in the Late Bronze Age… but it wasn’t coming from anywhere near the southern Levant.14 Where on earth was all this tin coming from? Where was the tin ore, or cassiterite, being mined?

In this post we’re going to look into the problem of where exactly the southern Levant’s Late Bronze Age source of tin was. As we’ll see in a bit, until very recently this was one of Near Eastern archaeology’s most baffling problems.

Ancient sources of Copper

Archaeologists have had no problem working out the source of copper used during the Late Bronze age. Though there were copper mines in the southern Negev and in the Jordan valley15, the bulk of the copper mined during the period came from Cyprus.16 As Papasavvas explains,

During the Late Bronze Age Cyprus was a major supplier of copper to Eastern Mediterranean empires, states and small kingdoms. It is only due to the island’s prolific copper resources that Cypriots were able to enter the sophisticated, geopolitical network sustained by powers such as Egypt and Assyria. In this context, Cyprus appears to have produced and distributed tons of copper to the entire Mediterranean and beyond… On the basis of this widespread circulation, it can be deduced that Cypriot copper must have become a key component for the development of bronze industries in the Eastern Mediterranean.17

As Papasavvas goes on to explain, the Cypriots were so concerned with flooding the market with their copper that for a long time they didn’t use any of it to produce bronze for themselves.

Copper in ancient texts

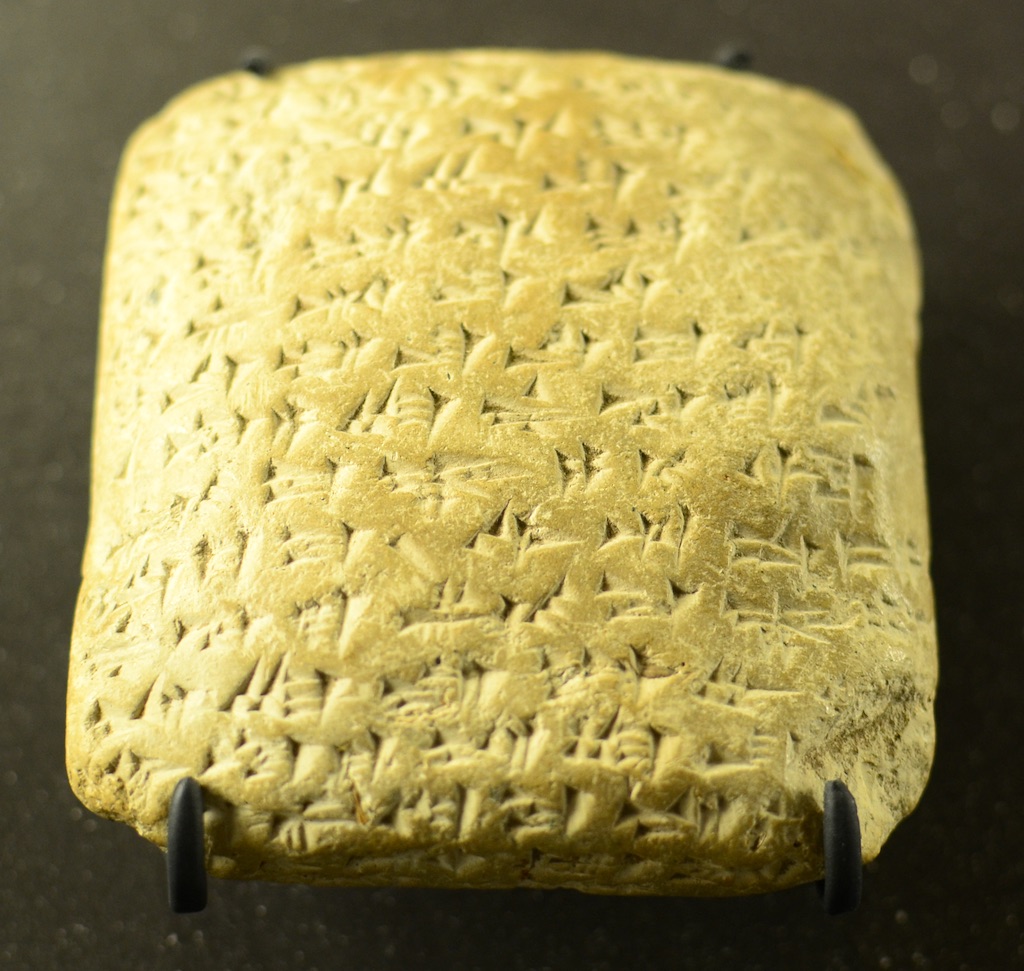

Ancient sources confirm Cyprus as being the dominant source of copper for the ancient Near East in the Late Bronze Age, the Amarna correspondence being the most well known. As an example, here’s a quote from a letter to Pharaoh from the king of Alašiya18, i.e. Cyprus, apologising for sending only a “small” amount of copper:

EA 35. 10-15: “I herewith send to you 500 (talents) of copper. As my brother’s greeting-gift I send it to you. My brother, do not be concerned that the amount of copper is small. Behold, the hand of Nergal is now in my country; he has slain all the men of my country, and there is not a (single) copper-worker.”19

This is not the only Amarna letter mentioning tremendous amounts of copper being sent from Cyprus to Egypt that we could have chosen to look at, it just happens to be the one that also mentions a plague20 – “the hand of Nergal” – and so hits close to home during the Coronatide of 2020. 500 talents is roughly 15,000kg, or, for any American readers, 33,000 pounds. If this is “all” that a plague-stricken nation could come up with (taking the Cypriot king’s excuse at face value), how much more could they produce when the miners were healthy? Cyprus really did produce vast amounts of copper.

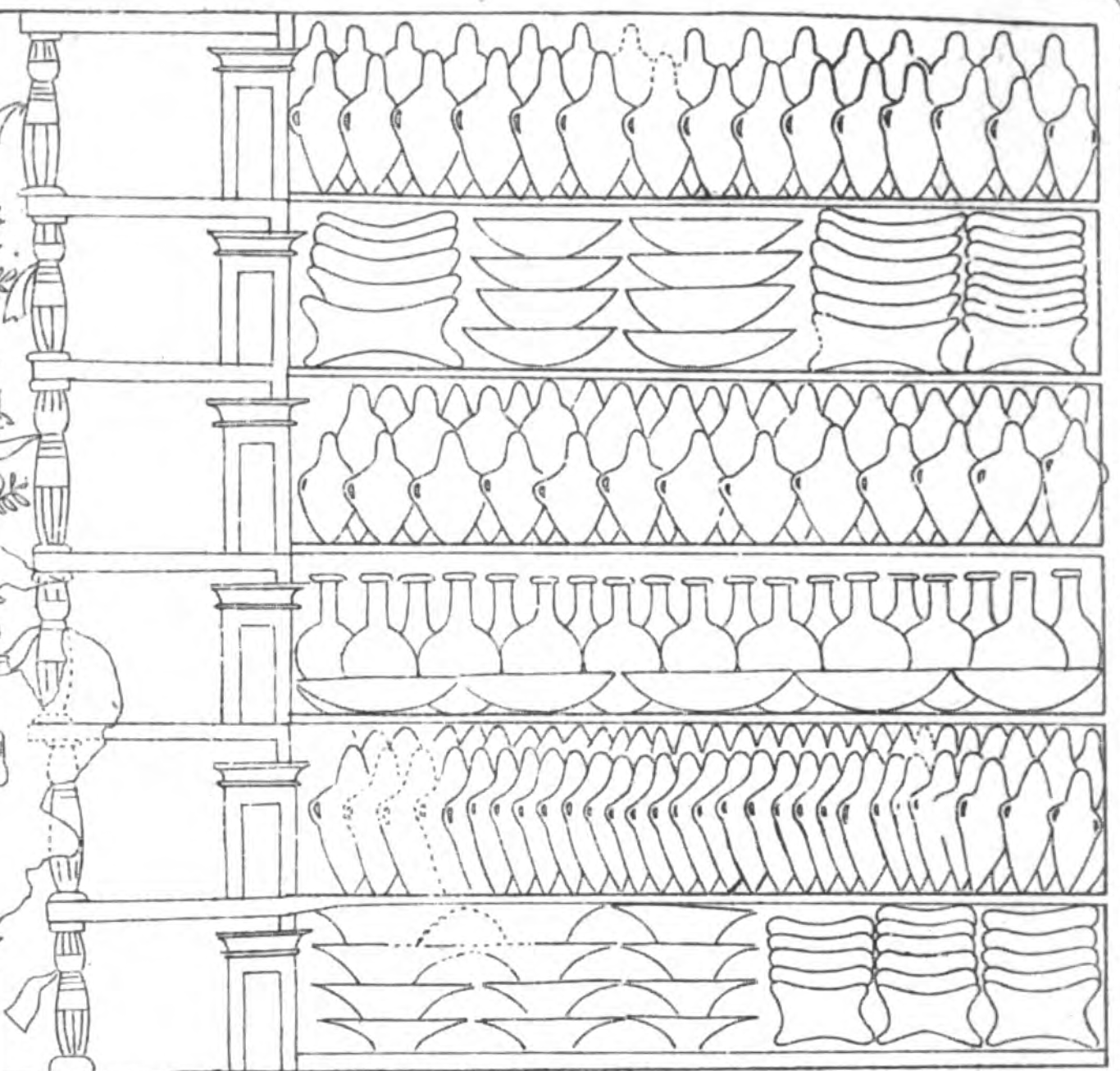

There are a number of Egyptian reliefs that contain representations of copper ingots; one of the more well known examples being in Amarna, on the eastern wall of the Late Bronze age rock cut tomb of Meryra, the monotheist heretic High Priest of Aten21:

There’s also this facsimile of a depiction from the Tomb of Rekhmire of a Syrian carrying a copper ingot on his shoulder22:

The unsolved problem of the source of tin

As we’ve already indicated, the Late Bronze age source of tin has been much more elusive. In fact, until very recently, no one knew where it came from. As Galili explains,

One of the most significant unsolved problems in Mid-Eastern archaeological research is the problem of tin supplies in the late Bronze Age…23

Others pressed the point harder:

Tin remains the enigma of bronze metallurgy, simply because no one knows where the tin for the early and middle Bronze Ages in Anatolia, Mesopotamia, and Iran came from. Moreover, we have as yet no real idea whether the first tin to be alloyed into bronze was stannite–the tin sulfide found with copper–or cassiterite–the tin oxide. Nor do we know where the first alloying occurred.24

As recently as 2017 leaders in the field of archaeometry can be found writing sentences like,

Unfortunately, the origin of tin remains as one of the knottiest problems in the archaeology of metal sources, specifically with regard to the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC.25

This problem was not unique to the Late and Middle Bronze Ages. The situation was just as true for the Early Bronze:

…finding the place of origin of the earliest tin is one of the major challenges in Bronze Age metallurgy. Many learned Papers have been written, full seminars been held, and expeditions been organized all aiming at answering the question into the provenance of this tin… Simply put, the problem is that near to where the earliest tin bronzes have been found (Mesopotamia, the Troad, Anatolia) there are no tin deposits known, and where there are tin deposits the local bronzes clearly are not the earliest ones.26

All sorts of locations for the source of Late Bronze Age tin have been suggested, amongst them Afghanistan27, Assyria28, Europe29, Uzbekistan30, and Thailand(!)31 However, these were all just guesses – no one knew where the tin used to create bronze in Late Bronze Age Canaan came from.

Though there are tentative indications that some may have come from Cornwall, sources in Iran, Central Asia or another closer source like Anatolia cannot at present be excluded.32

So, until recently the source of tin, so necessary to alloy with copper to create the defining metal of the epoch, clearly was a complete mystery.

Legends of the source of tin

It’s not like this mystery is only a recent thing either. Ancient texts bear witness to all sorts of conflicting ideas about where their tin came from. Let’s have a quick scan through those dusty tomes…

Herodotus (b. 484 BCE)

On this topic, Herodotus, the “Father of History/Lies”, wrote only the following:

Herodotus, Hist. 3.115.1–2 But concerning those in Europe that are the farthest away towards evening, I cannot speak with assurance; for I do not believe that there is a river called by foreigners Eridanus issuing into the northern sea, where our amber is said to come from, nor do I have any knowledge of Tin Islands [Gk: Κασσιτερίδας, “Cassiterides”33], where our tin is brought from… All we know is that our tin and amber come from the most distant parts.34

To add some context to Herodotus’ talk of “tin islands” it’s worth being aware that the above quote is followed by these two sentences:

Herodotus, Hist. 3.116.1: But in the north of Europe there is by far the most gold. In this matter again I cannot say with assurance how the gold is produced, but it is said that one-eyed men called Arimaspians steal it from griffins.35

It should be pretty clear that Herodotus is not much help. What little of this topic Herodotus shares with his readers is wrapped up in fantastical nonsense about gold-guarding griffins. What is useful about the above is that he demonstrates an awareness of a legendary source of tin in some islands way out west, somewhere in Europe, that he calls the “Cassiterides”. So, that’s something.

Timaeus (355-260 BCE)

Timaeus of Tauromenium in Sicily (355-260 BCE) wrote a 38-volume history of Greece and Rome from ancient time to his own day.36 Though his histories have not survived he is frequently quoted by later Greek and Roman historians. Pliny, in his Natural History, quotes Timaeus as saying that,

Plin., N. H. 4.30: …an island called Mictis is within six days’ sail of Britannia, in which white load [i.e. tin37] is found; and that the Britons sail over to it in boats of osier, covered with sewed hides.38

Mictis (or ‘Ictis’ as we’ll see a bit later) is a reference most likely to St Michael’s Mount39, a tidal island off the southern coast of Cornwall, England. Timeaus was way off on the bit about six days sailing – it’s no more than a 5 minute walk across to the island when the tide is out.

Posidonius (135-51 BCE)

Strabo is to Posidonius as Pliny is to Timaeus. We only have fragments of his writings, but Strabo, amongst others, quotes the 2nd-1st century BCE Greek stoic polymath.40 Here’s what Strabo tells us Posidonius wrote about where he thought tin came from:

Strabo, Geography 3.2.9: [Posidonius] says that tin is not found upon the surface, as authors commonly relate, but that it is dug up; and that it is produced both in places among the barbarians who dwell beyond the Lusitanians [western Spain] and in the islands Cassiterides; and that from the Britannic Islands it is carried to Marseilles.41

According to Posidonius, tin was found in the “Cassiterides” – islands somewhere out past Britain.

Diodorus Siculus (90-30 BCE)

Writing in the 1st century BCE, a later greek historian named Diodorus of Sicily provides us with a more developed legend – Phoenicians, enter stage left:

The Phoenicians in ancient times undertook frequent voyages by sea, in way of traffic as merchants, so that they planted many colonies both in Africa and in these western parts of Europe. These merchants succeeding in their undertaking, and thereupon growing very rich, passed at length beyond the pillars of Hercules, into the sea called the ocean.42

These daring Phoenicians, according to Diodorus, sailed out through the Strait of Gibraltar, and out into the Atlantic. The Greek historian continues with a description of what the Phoenicians found:

Now we shall speak something of the tin that is dug and gotten there [i.e. Britain]. They that inhabit the British promontory of Belerium, by reason of their converse with merchants, are more civilized and courteous to strangers than the rest are. These are the people that make the tin, which with a great deal of care and labour they dig out of the ground; and that being rocky, the metal is mixed with some veins of earth, out of which they melt the metal, and then refine it; then they beat it into four-square pieces like to a dye, and carry it to a British isle near at hand, called Ictis. For at low tide, all being dry between them and the island, they convey over in carts abundance of tin in the mean time. But there is one thing peculiar to these islands which lie between Britain and Europe: for at full sea, they appear to be islands, but at low water for a long way, they look like so many peninsulas. Hence the merchants transport the tin they buy of the inhabitants to France; and for thirty days journey, they carry it in packs upon horses’ backs through France, to the mouth of the river Rhone.43

This time there’s no mention of Cassiterides. According to Diodorus the tin that was brought to the Mediterranean in ancient times came from Britain; specifically Belerium – an ancient name for Land’s End in Cornwall, England44 – which he describes as being a four day sail from the continent. The tin ore was dug out of the ground, smelted, made into ingots, and then brought to Ictis (almost certainly the same location as Timaeus’ “Mictis”, i.e. St Michael’s Mount). From there it was put on ships and sailed to France where it would be be transported overland to the Mediterranean coast at the mouth of the river Rhone (modern Camargue in southern France).

The one thing going for Diodorus’ account is that it’s talking about an ancient tin source, not the one of his own day. So that’s something.

Strabo (62 BCE-24 CE)

Strabo, a Greek historian, makes it clear that his understanding was that the Cassiterides are not Britain:

Strabo, Geography 2.5.15: Northward and opposite to the Artabri are the islands denominated Cassiterides, situated in the high seas, but under nearly the same latitude as Britain. From this it appears to what a degree the extremities of the habitable earth are narrowed by the surrounding sea.45

So, the Cassiterides are at the same latitude as Britain, but they’re not Britain. Later in his Geography he tells us that,

Strabo, Geography 3.5.11: The Cassiterides are ten in number, and lie near each other in the ocean towards the north from the haven of the Artabri. One of them is desert, but the others are inhabited by men in black cloaks, clad in tunics reaching to the feet, girt about the breast, and walking with staves, thus resembling the Furies we see in tragic representations. They subsist by their cattle, leading for the most part a wandering life. Of the metals they have tin and lead; which with skins they barter with the merchants for earthenware, salt, and brazen vessels.46

According to Strabo the Cassiterides were a collection of 10 islands lying close to each other. Definitely not Britain then.

And now for Strabo’s snowball that’s only grown in size as it’s rolled down the slopes of history, crushing every attempt at critical thought in its path:

Strabo, Geography 3.5.11: Formerly the Phœnicians alone carried on this [tin trading] traffic from Gades, concealing the passage from every one; and when the Romans followed a certain ship-master, that they also might find the market, the shipmaster of jealousy purposely ran his vessel upon a shoal, leading on those who followed him into the same destructive disaster; he himself escaped by means of a fragment of the ship, and received from the state the value of the cargo he had lost. The Romans nevertheless by frequent efforts discovered the passage, and as soon as Publius Crassus, passing over to them, perceived that the metals were dug out at a little depth, and that the men were peaceably disposed, he declared it to those who already wished to traffic in this sea for profit, although the passage was longer than that to Britain.47

Yeah, so apparently the Phoenician trade network spanned the length of the Mediterranean, out into the Atlantic, and up all the way to Cornwall. As anyone unlucky enough to strike up a conversation about ancient Cornish history with a local in a pub in Cornwall will know, this legend has stuck. It is deeply embedded in the Cornish psyche. The Phoenicians were regular visitors to Cornwall, and that’s that.

Pliny (23/24-79 CE)

Following the lead of the previous historians, the Roman senator Pliny joins in with the “Cassiterides” theme. He tells us that some guy called,

Plin., N. H. 7.57: Midacritus was the first who brought tin from the island called Cassiteris.48

Wait, so now the tin source is a single island? Earlier in his Naturalis Historia Pliny gives us a rough indication about where this Cassiteride island is:

Plin., N. H. 4.36: Opposite to Celtiberia [central-eastern Spain] are a number of islands, by the Greeks called Cassiterides, in consequence of their abounding in tin: and, facing the Promontor of the Arrotrebæ, are the six Islands of the Gods, which some persons have called the Fortunate Islands.49

Oh. It’s plural again. And… these islands are “opposite” central-eastern Spain?

Dionysius Periegetes of Alexandria (early 2nd century CE)

During Hadrian’s rule in 117-138 CE, Dionysius Periegetes of Alexandria wrote his Description of the Known World, based, he claims, on ancient sources.50 He includes a long list of islands both inside and outside the Mediterranean Sea. Before explaining that “no other among all the islands is equal to the British Isles,” he mentions that,

Dion. Periegetes: 560-569 Below the Sacred Cape, which they say is the headland of Europe, the islands of the Hesperides, the birthplace of tin, are inhabited by the rich people of the illustrious Iberians.51

Now the tin islands are populated by rich Spaniards?

Sifting the stories

From these ancient sources have developed all sorts of fantastic legends. Probably the most well known and most ridiculous is the inspiration behind William Blake’s most famous poem,

And did those feet in ancient time

Walk upon England’s mountains green

And was the holy lamb of God

On England’s pleasant pastures seen.

The details of the legend vary but the thrust of it is that the boy Jesus accompanied Joseph of Arimathea – a tin merchant who travelled on Phoenician ships – on one of his business trips to England.52

The legend grew in the telling, e.g. during the 12th century the monks at Glastonbury Abbey extended the legend to make the tin-trading Joseph of Arimathea the ancestor of King Arthur53 (of “We do routines, and chorus scenes, with footwork im-pec-able” fame).

But, what reliable historical information can we really get from the writings of Herodotus, Timaeus, Posidonius, Diodorus Siculus, Strabo, and Pliny on the topic of where the Late Bronze Age source of tin was that supplied the Levant?

Well, Herodotus didn’t claim to know much, just that tin came from some islands called “Cassiterides” which lay somewhere far away. And, since his sensible-sounding stuff is mixed in with obvious nonsense it’s hard to know what to take seriously. Also, given he was writing in the mid 5th century BCE about where tin in that period came from he doesn’t shed much light on where Canaanites were getting their tin from in 1300 BCE, almost a thousand years earlier.

Timaeus claims that tin was found on an island named ‘Mictis’, 6 days’ sail from Britain. Though probably a reference to St Michael’s Mount, the 6-days-sailing bit means he could be talking about anywhere from northern Spain, to Ireland, to the Belgian coast. Timaeus was also writing of his own day which was later than Herodotus’ – sometime in the 4th-3rd century BCE, again, around 1000 years later than the Late Bronze Age. Not much help.

Posidonius’ claim that tin came from islands he called “Cassiterides” located somewhere out past Britain also isn’t much help – he was writing of the tin source of his own day, and that’s more than 1000 years after the period we’re interested in.

In the 1st century BCE Diodorus told us that the merchants of his day traded for tin at ‘Ictis’, a tidal island in Belerium (i.e. Cornwall). The tin was dug out of the ground by slightly-less-savage-than-average Britons, and it would be shipped from Ictis to France. There’s no link in the text between the tin-trading details and the preceding story about the Phoenicians going through the Strait of Gibraltar. Even so, Diodorus is writing of tin trading in his own day which was 1,200 years after the close of the Late Bronze Age. There’s nothing here of any historical value for anyone interested in the source of the tin that was alloyed with copper in Canaan in the Late Bronze Age.

Also writing in the 1st century BCE Strabo shared his understanding that Phoenicians, previous to his time, sailed to the Cassiterides to trade tin. Interestingly he makes out that the Cassiterides aren’t part of the British mainland; rather they are a collection of small islands lying close to each other further out than Britain from the continent. He seems for all the world to be describing the Scilly Isles.54

The geographical accuracy of Strabo’s claim raises the question: is there tin in the Scilly Isles? It turns out that, yes, there is:

The above map has circled on it some old costean shafts used to mine tin on Tresco, one of the north-westerly Scilly Isles. You can see them marked on this Ordnance Survey map. However, these tin mines don’t date to the 13th century BCE. Penhalluric tells us that they were “probably dug in the 17th to 18th century”55 CE – around 3,000 years later than the time period we’re interested in.

So yeah, tin is present in the Scilly Isles.56 But, is there a significant amount of tin in the Scilly Isles? No. Penhalluric continues:

While it is true that some of the Tresco veinlets contain tin, it is clear from the very shallow nature of the ‘Costean shafts’ or trial pits that they contained nothing of any importance… Those who have sought to equate the Cassiterides with the Isles of Scilly clutch at straws… The Isles of Scilly can have played no part in the prehistoric tin trade other than acting as an anchorage for trading ships, either by design or to escape the worst of the Atlantic weather.57

There is vastly more cassiterite in Cornwall and Devon than any negligible amount that is or was in the Scilly Isles. Anyone looking for tin wouldn’t bother with the Scilly Isles when to get there they’d have to sail straight past the comparatively massive tin ore deposits in Devon and Cornwall.

Strabo’s more interesting claim that “the Phœnicians alone carried on this [tin trading] traffic from Gades, concealing the passage from every one”, as cool as it is, doesn’t help us – for two reasons. The first reason is that the Phoenician port of Gades was only established in the 8th century BCE58 – so whatever trading Strabo is talking about, it wasn’t happening in the Late Bronze Age – it is at least 500-600 years too late. The second reason is that, as Penhalluric explains in his chapter, The Phoenician myth, the Phoenician connection with Britain has been shown to be nothing more than patriotic bed time stories.59 He tears the arguments from etymology limb from limb; he points out that though “no Phoenician object has ever been found in Britain does not deter the supporters of the voyagers from the Levantine coast,” and chases down the origins of the local stories of mines that supposedly supplied the tin used for the creation of Achilles’ shield, the Tabernacle, and the very Temple of Solomon and shows them to be plain fantasy.60 The chapter makes for comical reading. One paragraph is particularly insightful:

Perhaps it was Cornwall’s strong attachment to Methodism which made its inhabitants yearn for some direct link with the biblical lands. And who better to see help from than Solomon and Christ? The Phoenician ruler Hiram I of Tyre (970-936 BC) made a treaty with Solomon allowing Phoenicians to use the port of Ezion Geber on the Red Sea, and permitting his craftsmen to work in the temple of Jerusalem. As a result, the temple exhibited Phoenician motifs and used bronze, the tin for which naturally must have come from Cornwall. That Phoenician involvement beyond the Pillars of Hercules [i.e. Strait of Gibraltar] cannot have existed much before 800 BC counts for nought.61

The whole “Phoenicians sailed to England in the Late Bronze Age” nonsense really needs to be dropped. It just didn’t happen.

Coming back to our ancient sources, Pliny tells us that the Cassiterides are opposite the northern coast of Spain. Spain and Portugal do have regions where tin is found. In fact,

The Iberian tin belt is located in the northwest region, covering an area of c.200,000 km2, in an extension of c. 600 km northwest to southeast. It is the largest area with tin available in Western Europe.62

Though much of this tin belt is inland, there are many rivers flowing through it that “would make the interior tin sources very accessible to long distance maritime trading.”63 The remains of several Phoenician settlements and merchant outposts have been found in the estuaries where these rivers meet the Atlantic. Though they were constructed at the earliest only at the end of the 8th century or the beginning of the 7th century, there appears to have been Phoenician contact with the area beginning in the 9th century.64 This lines up well with the chronology of the Logrosan mine located almost exactly in the centre of the Iberian peninsula – mining activity, known to have been performed by the Tartessian65 people began there at the beginning of the 8th century BCE.66 Assuming the Phoenicians were trading tin at these river mouth sites, at best that’s 300 years too late to be of any help to us when working out what was happening in the Late Bronze Age.

Finally, Dionysius Periegetes of Alexandria tells his readers that the islands from where tin came were located “below the Sacred Cape”. Dion interprets the text as referring to the area south of Brittany in north-western France. Today there are no such islands, but Dion explains that in antiquity, before the Loire estuary silted up, there were indeed islands in the river mouth covered in Bronze Age settlements, and that it is to these islands that Dionysius referred.6768

Dion’s interpretation is an unconventional one – the conventional understanding is that Dionysius is referring to islands off north-western Spain.69 This isn’t to say that there was no tin ore in southern Brittany – there was.70 But was there enough tin ore to supply the needs of the rest of the Mediterranean? Well, as the excellently named authors of a paper on the topic tell us, “it is not yet possible to determine if the tin production in the [Armorican Massif] was sufficient to supply the local bronze production during this period.”71 Only a relatively puny amount of tin was produced in Brittany during the period we’re interested in:

Although many tin deposits are known in Brittany, this region is generally not considered as an important tin producer, whatever the period.72

What we learn from the ancient sources

So, stepping back, the situation with the ancient sources is… pretty hopeless. We’ve got interpretations of various texts that claim that ancient sources of tin were, variously, the Scilly Isles, Cornwall and Devon, St Michael’s Mount, islands in the mouth of the river Loire, and some islands off the north-eastern coast of Spain. On top of that, not a single one of these ancient sources is talking about the Late Bronze Age; they’re all covering time periods long after the era we’re interested in.

While you can find all sorts of passionate but logical-fallacy-ridden defences of the notion that the ancient sources tell us that Britain7374 was Canaan’s Late Bronze age source of tin, the situation is summed up well in the Oxford Classical Dictionary:

The unambiguous evidence about the location of the Cassiterides in the classical sources suggests that it was a partly mythologized generic name for the sources of tin beyond the Mediterranean world and not a single place. The absence of archaeological evidence for any pre-Roman iron age trade with the tin-producing areas of SW England supports this.75

Basically, if you asked someone in antiquity where the Cassiterides were, the most likely answer you’d have received would be a non-committal hand-waving in a general westerly direction and, “Out past the Strait of Gibraltar somewhere maybe.”

As far as figuring out where people in Canaan were getting their tin from during the Late Bronze Age, we’ve not made any progress whatsoever. The written sources tell us nothing useful. We need to turn to the archaeological evidence to solve this “greatest enigmas of the period.”76

The archeological evidence that helped solve the puzzle started to come to light in the late 1970s…

Israeli Underwater Archaeology

Over the last 60 years or so, twenty-two Bronze Age shipwrecks have been discovered lying off the Israeli coast. Some are only metres from the shore, others are several hundred metres out to sea, and their cargoes – or what remains of them – vary. At six of those shipwreck sites metal ingots were found – mostly copper. At only three of those six sites did they find tin ingots.77 They are,

- Kfar Samir North78

- Kfar Samir South

- Hishuley Carmel

Kfar Samir North

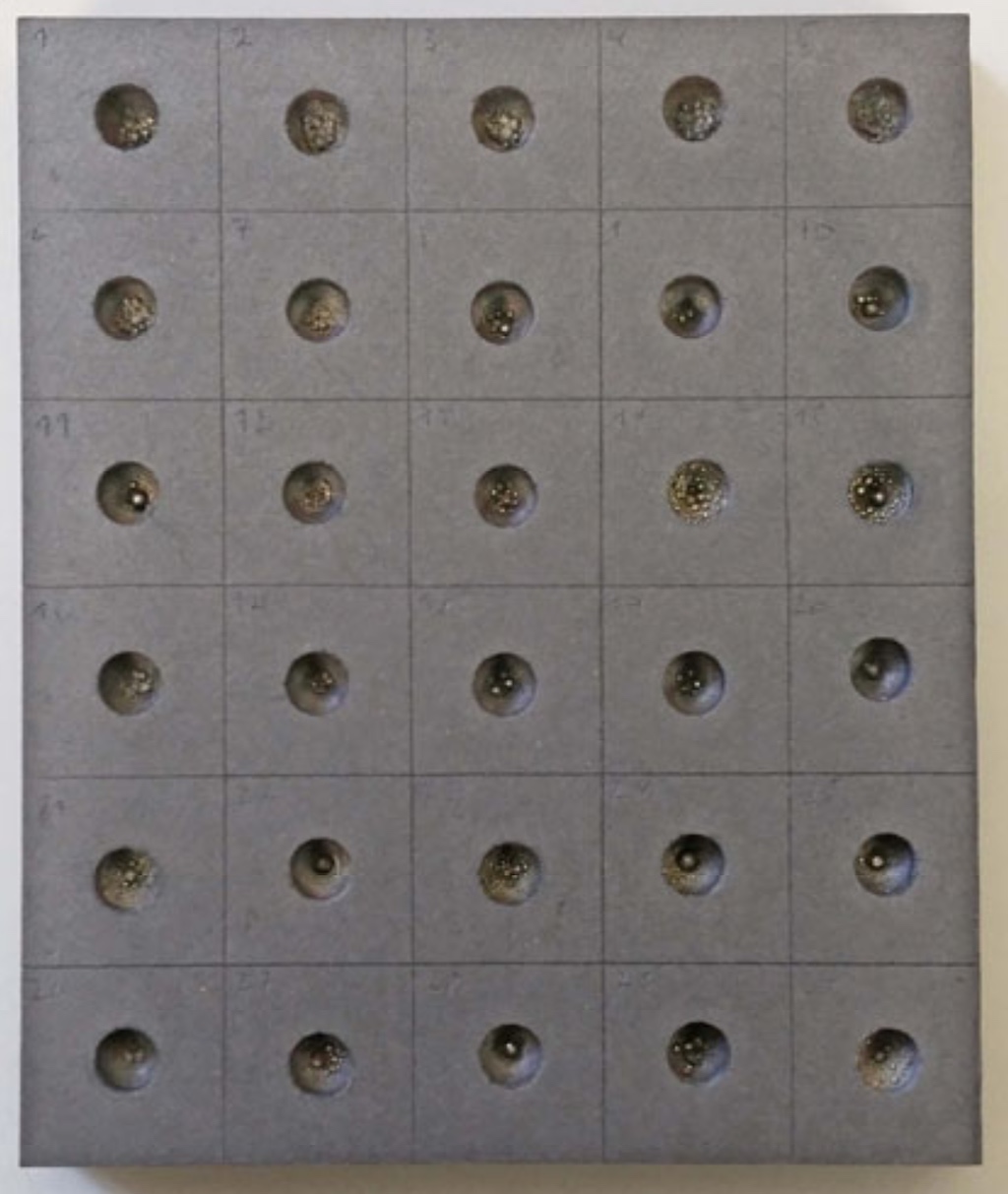

At some point in the 1970s, a fisherman by the name of Adib Shehade was bobbing about in his boat in the shadow of Mt Carmel, just south of Haifa, opposite the town of Kfar Samir. At around 150 metres from the shore he discovered 30 rectangular tin ingots on the sea floor and hauled them up onto his boat. When he got back to the shore he took them to a tinsmith, who, over the next few years used them to fix car radiators. Only four of them remained by the time the University of Haifa found out about the ingots and bought them up.79 The rest of the tin is probably rotting away in Israeli scrap yards.

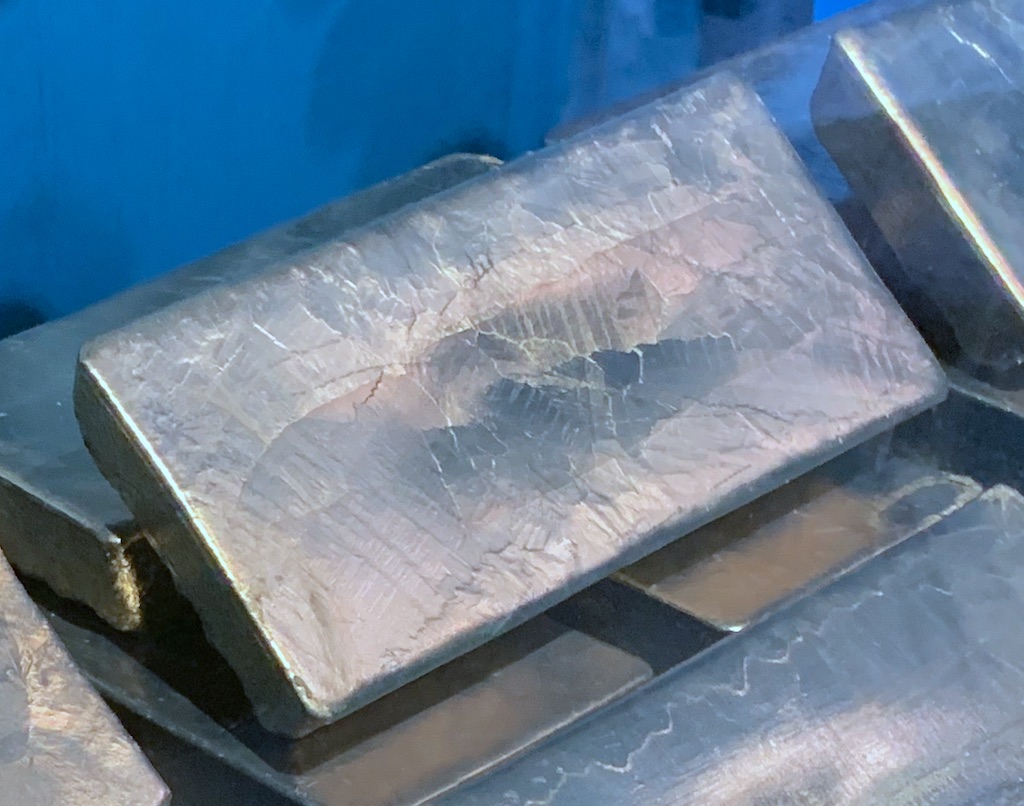

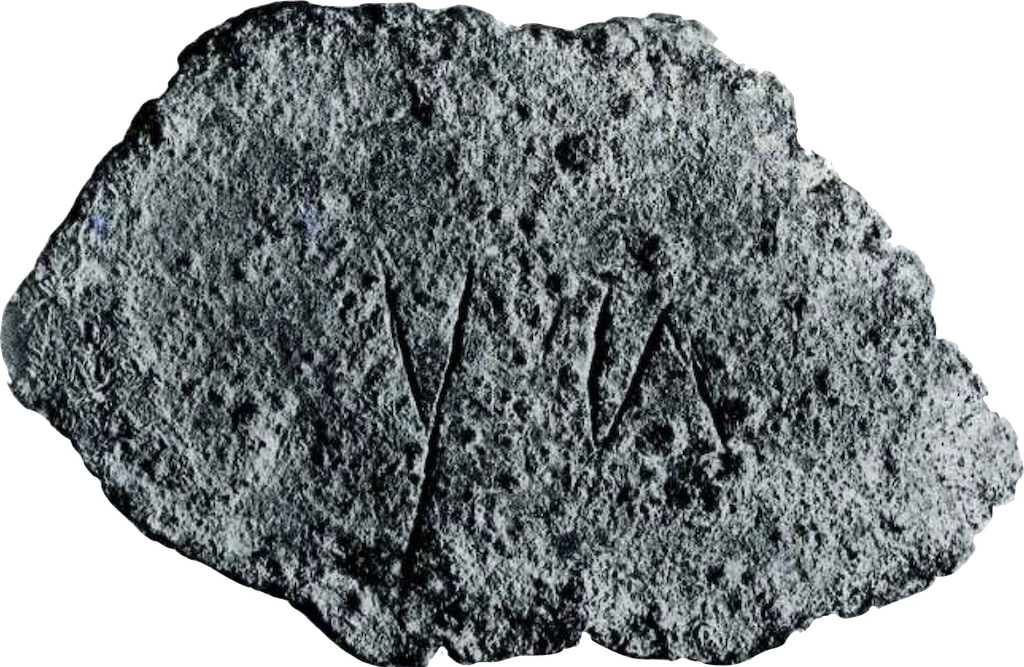

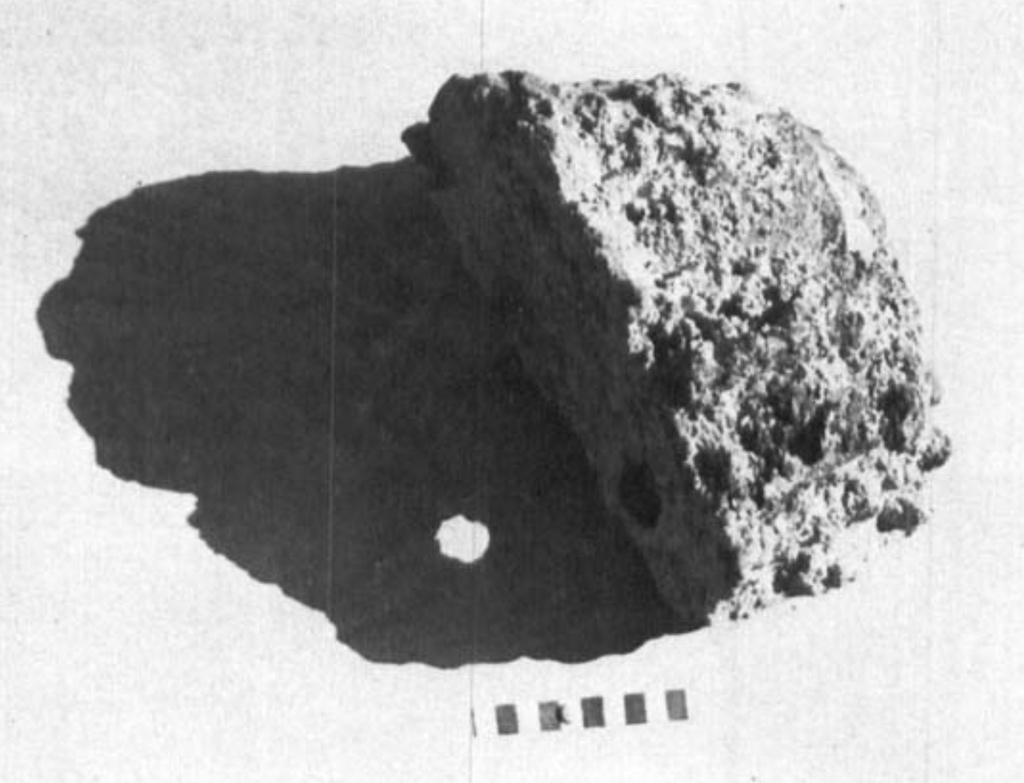

Investigation in 1977 revealed the ingots to be from the Late Bronze Age – they were stamped with a sign from the Cypro-Minoan script used between 1600 and 1100 BCE. Chemical analysis revealed the ingots to be 95% pure; 4.5% of the remainder being magnesium that originated from the sea.80 So, when they were first cast, these ingots were about as pure as you could ask for.81

Sadly, because the archaeological context is unknown – the ingots were fished out of the sea – not a great deal about these ingots could be determined back in the ‘70s.82

Hishuley Carmel

In the winter of 1982, just 1.5km south of where the Kfar Samir North ingots were found, a storm shifted the sand that ordinarily lay beneath the waves. Exposed probably for the first time due to sand quarrying in the area that began at the establishment of the State of Israel83, artefacts from an ancient shipwreck that had laid hidden beneath the waves for 3,200 years were suddenly visible.84

Between newly formed sand bars only a few tens of metres from the shore, four limestone anchors each weighing around 250kg were sticking up out of the clay, seemingly exactly where they’d first fallen when the ship they served went down.85

Around 30 metres south-west of the anchors lay a ridge of storm-shifted sand. Using metal detectors, the scuba divers performing a survey of the area discovered 5 metal ingots embedded in the clay, around 25cm below the sand.86 Of these ingots, one was copper and the other four were tin.

The presence of tin ingots attracted great interest – this was only the second time that such artefacts had been found in their archaeological context anywhere in the Mediterranean. The first discovery of tin ingots undisturbed from their context came earlier in 1982 from the Uluburun shipwreck on Turkey’s southern coast.87 The discovery at Kfar Samir, however, was the first time tin ingots had been found anywhere in the Levant.

The tin ingots weren’t in perfect shape – parts of them had clearly been carved off in antiquity. Based on this it’s thought that the ship’s crew used some of the tin to create bronze on their journey, making the vessel a sort of “sailing workshop.”88

When the ingots were analysed it was determined that,

…the group of five ingots is of extremely high purity cassiterite [i.e. tin ore]. The cassiterite used in making the bars came from the same location, probably alluvial. The smelting techniques varied sufficiently to alter the amounts of the trace element impurties, or the cassiterite was collected from a number of locations, but in the same general vicinity.89

So, the cassiterite used to make the tin ingots came from a single area. But that’s as far as the scholars were able to go at the time. The tin was pure enough that the lead normally found in tin was too small to be workable with the technology they had in the early-mid 1980’s – no further analysis was possible. The trail back to the ingots’ source had gone cold.

The following year, in 1983, a rescue excavation turned up more anchor stones, more copper ingots, and, critically, more tin ingots. More rescue excavations were done over the next few years (1984, 1992, and 2004), and even more tin ingots were found. By the time the archaeologists were done, a total of 14 tin ingots weighing a total of 206 kg had been found at Hishuley Carmel.90

Chemical analysis performed in 1999 showed the tin ingots to be 91% pure.91 Not a bad effort.

Kfar Samir South

In 1985, 500 metres south of Kfar Samir North (and 900 metres north of Hishuley Carmel), and 100 metres out from the shore, another shipwreck site was discovered.92 Rather like the Hishuley Carmel site, five stone anchors were found on the sea floor 3 metres below the surface, seemingly belonging to one ship. Five metres away from the stone anchors lay an Egyptian sickle sword, with 8 bar-shaped tin ingots and 8 lead ingots in the same vicinity.93 One of the tin ingots weighed 36kg94; the 8 in total weighed 80kg!95

Just like the other two tin ingot shipwrecks, this site and its artefacts have been dated to the Late Bronze Age, specifically, the 14th-13th centuries BCE.96

Fingerprinting the ingots

With these tin ingots scholars finally had something to work with as they tried to solve the baffling problem of where all the tin came from that was necessary for the manufacture of all the bronze created in the southern Levant’s Late Bronze Age.

There was, however, a problem – there wasn’t the tech available to detect where the tin had come from. The raw material had now been found, but there wasn’t the means to work out its source. The researchers knew what was needed – as Wertime explained back in 1973,

For the time being, a variety of techniques will have to be brought to bear on the tin problem; including… the development of isotopic and other means of fingerprinting tin.97

More than 20 years later the same suggestions were still being made with Gale proposing in 1997 that,

the study of tin isotopic variations could provide a method for targeting ancient bronze artefacts for provenancing by lead isotope analysis98

The ability to perform more precise chemical analysis on tin ingot samples was critical. Without them the source of tin would remain a mystery.

Lead isotopy

It didn’t take long for papers to be published on the topic. In 1999 a groundbreaking paper, Tracing ancient tin via isotope analyses, explained how measuring the isotopic composition of the trace amounts of lead in various metals had been used in working out where the metal originated. The explanation from the paper is worth quoting in full:

during the past decades the isotopic composition of lead has been used with advantage in tracing chalcolithic and Bronze Age metals back to their ore sources. The method utilizes the fact that three of the four stable lead isotopes, those of atomic mass 206, 207, and 208, are continuously being produced by the radioactive decay of omnipresent uranium and thorium in such a way that the isotope abundance ratios, say 208Pb/206Pb, 207Pb/206Pb, 204Pb/206Pb or also 206Pb/204Pb, 207Pb/204Pb, and 208Pb/204Pb, are affected to a different degree. The result is that different ores may contain lead with distinctly different abundance ratios and, since this isotopic signature is only imperceptibly changed in all subsequent metallurgical steps on the way from ore to artifact, different artifacts can also be expected to be distinguishable by the isotopic composition of their lead.99

For those whose recollection of their school chemistry lessons is as poor as mine, here’s an oversimplification that may help: when lead is first formed, it contains a specific amount of certain lead isotopes. Over time those isotopes “decay” at a known rate. So, if you can measure the amount of particular lead isotopes in a piece of lead, you can tell how old it is by measuring how much lead isotopes are still present – the fewer isotopes present, the older it is.

By measuring trace lead in a tin ingot an “isotopic signature” for that ingot could be determined – a ratio between lead’s four stable isotopes could be evaluated, and based on how much of each isotope was present compared to other isotopes, the age of the metal in the ingot could be determined. And, by calculating the age of different tin sources around the world, tin ingots could be matched up with their source.

In reality, this method cannot be used to precisely locate an ingot’s source – it can only be used to exclude sources.100

To give an example, a tin ingot containing lead that is, say, 1 million years old cannot come from area A where the lead is 20 million years old; but, the metal could come from areas B, C, and D where the lead in the ground is 1 million years old. In this example we can say with confidence that the tin in question is definitely not from area A, but it could be from any of the areas B, C, and D.

Lead isotopes can tell us where tin isn’t from, not necessarily where it is from.

The paper anticipates the obvious question: “But why the detour via the isotopy of Pb [i.e. Lead] in the first place? Why not measure the isotopic composition of Sn [i.e. Tin] itself? After all, Sn has ten stable isotopes -as compared to Pb that has only four-, and with Sn one would analyze not a proxy but the element one is really interested in.”101

Why waste time measuring lead isotopes when you could be measuring tin isotopes? The paper goes on to answer that due to the fact that “there are no radioactive elements whose decay would affect the abundance of one Sn isotope or the other”, there’s nothing useful to measure. Basically, the tin isotopes provide no reliable ‘radiometric clock’ that can be used to determine the age of a piece of tin.102 As a result,

in spite of the fact that it has ten stable isotopes [tin] is a much less useful element for isotope tracing than is lead.103

Indeed, the authors go so far as to say that,

We therefore consider the chances bleak that the isotopic composition of tin might be of any help in tracing tin back to its ores.104

Tin isotopy

The notion that using tin isotopy to locate a tin ingot’s source was too hard seems to have goaded researchers on. Over the next 20 years –even up to the time of writing this post– papers on the topic are being published.105 The steady stream seems to have begun in earnest with a paper published in 2002 with the promising title, Precise determination of the isotopic composition of Sn [Tin] using MC-ICP-MS. It documents processes that show that “it is possible to measure the isotopic variation in Sn [tin] using the IsoProbe.”106 I’m not going to even pretend to understand the rest of the paper107, but whatever an IsoProbe is, it’s now on my Christmas list.

With that technical challenge out of the way, in 2010 a paper with the hopeful title, Tin isotopy – a new method for solving old questions was published. It demonstrated that different bits of tin from the same source do have the same isotope ratios, and therefore can be both differentiated between and traced back to their source:

Systematic investigations of ores from several deposits in the Erzgebirge region [a hilly area in eastern Germany] and Cornwall, as reported here, demonstrate that the tin isotope ratio of a source is widely homogeneous. On the other hand, we found significant differences between ores from different sources. This provides the foundation for a useful procedure to be used for tracing the ancient tin via tin isotopes.108

They achieved this by testing the isotopy of many cassiterite samples from a variety of locations, comparing their results.109

Though questions remained, such as the reason for the different isotopy across regions, the important result was this: our results show that local differences in the isotopic composition of tin do exist,110 and, it is possible to distinguish between ores from the Vogtland, the Erzgebirge and Cornwall111.

So, cassiterite samples can be traced back to their source.

The final technological break through that needed to be made was written up and published in 2017 in a paper entitled, Tin isotope fingerprints of ore deposits and ancient bronze. The paper “discusses methodological issues in measuring tin isotope ratios in tin ores and metal objects” (emphasis mine). The ability to measure tin isotopes in bronze and tin artefacts from the bronze age (as opposed to cassiterite) was finally here.112

Pinning down the source

Though further papers went on to clarify and provide more details,113 it was a 2019 article in PLOS One with the brief title, “Isotope systematics and chemical composition of tin ingots from Mochlos (Crete) and other Late Bronze Age sites in the eastern Mediterranean Sea: An ultimate key to tin provenance?”114 that finally put all the pieces together.

It took the approach of measuring the isotope ratios of lead and tin as well as the trace elements in a collection of tin ingots found in Mochlos (in an ancient store room on the tiny island off eastern Crete), Uluburun (a Late Bronze Age shipwreck found off the southern coast of Turkey), and the three shipwreck sites on Israel’s coast; Kfar Samir North, Kfar Samir South, and Hishuley Carmel, comparing them to the age of the cassiterite from different regions that have produced it (in large quantities or small).

Different tin ore bearing regions were formed at different times in the earth’s history115:

| Tin source | Formation (Million years ago) |

|---|---|

| India | 1500-700 |

| Eastern Desert, Egypt | 650-530 |

| Iberian Peninsula | 336-280 |

| Brittany | 320-315 |

| Erzgebirge | 320-280 |

| French Massif Central | 317-289 |

| Sardinia | 307-289 |

| Cornwall/Devon | 295-270 |

| Zagros Mountains | 230-180 |

| Slovak Ore Mountains | 150-120 |

| Pamir, Tadzhikistan | ~100 |

| Hindu Kush | ~80 |

| Mourne Mountains | 60-50 |

| Kestel | 20 |

| Hisarcık | 2 |

The lead content of the Israeli ingots was shown by its lead isotope ratios to be approximately 291 million years old, plus or minus 17 million years, giving a range of 308-274 million years old.116 As explained above, this allows us to exclude a whole load of tin sources form the list of potential sources for the tin ingots. For example, since the tin in Egypt’s eastern desert was formed between 650-530 million years ago, tin that’s 308-274 million years old cannot have come from there. Meanwhile tin from the Hindu Kush was formed approximately only 80 million years ago, so that can’t be the source of the tin ingots either.

This process of elimination based on the ingots’ lead isotopy narrows down their source to one of:

- Cornwall/Devon

- Erzgebirge range

- Spain

- French Massif Central

- Brittany

- Sardinia

– basically, the European sources of tin.117

This is immediately useful in showing that the Late Bronze age source of tin for the southern Levant could not have been Asian or African – two commonly proposed solutions to the “tin problem”.

Next, the tin isotope ratios. These are a little more tricky.

Due to having identical δ124Sn values, all the Kfar Samir North ingots definitely came from the same tin mine. And since the Hishuley Carmel ingots share the same tin isotope values as the Kfar Samir North ingots, they also came from the same mine.118 Based on having slightly different tin isotope ratios, though the Kfar Samir South ingots came from the same area as the other two sets of ingots, they must have come from a different mine.119

When compared to the European tin sources, the tin isotope ratios present in the Israeli ingots matches the tin ore found in the Erzgebirge, a few regions on the Iberian peninsula, and Cornwall. It does not match the tin ore found in Brittany, neither does it match that of Sardinia, or the French Massif Central.120

So, we’ve been able to create a pretty concise shortlist of tin sources for the Israeli tin ingots. Using the lead isotope ratios we were able to establish that the tin was coming from somewhere in Europe, not Asia or Africa. The tin isotopes helped us eliminate most of the European sources, leaving only three candidates:

- Erzgebirge

- Iberian Peninsula

- Cornwall

There’s one more thing we need to look at in order to figure out which of those three candidates was the southern Levant’s Late Bronze Age source of tin: trace elements.

Trace elements of antimony, silver, selenium, indium, tellurium, mercury and gold, specifically.121 If tin ingots from a known source could be found that had the same amount of trace elements as the Israeli ingots, we’d be able to nail down exactly where the Israeli tin ingots came from. Amazingly, such tin ingots have been found and studied.

It’s time for a tangent.

English shipwrecks

It wasn’t only off Israel’s coast that tin ingot bearing shipwrecks were being discovered in the late 20th century; the same was happening on England’s southern coast.

Moor Sand, near Salcombe, Devon

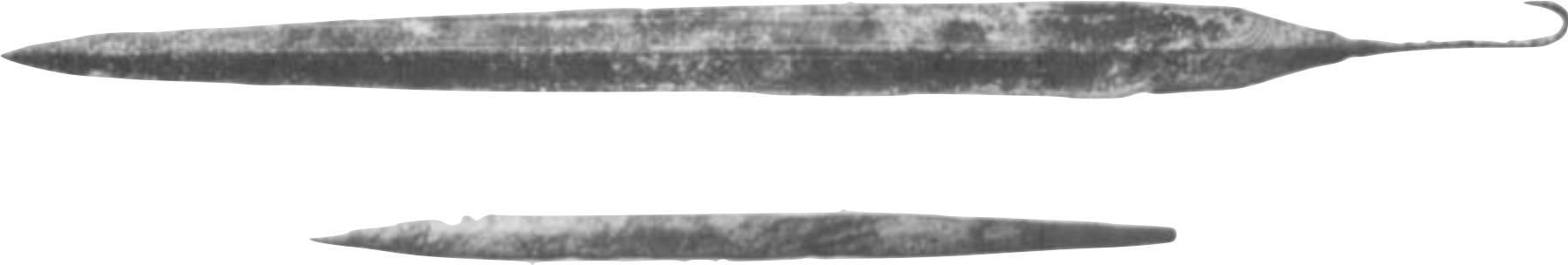

On the 4th of July, 1977, Philip Baker was leading a beginner’s Youth Hostel Association “Adventure Holiday” underwater swimming course off Moor Sand, near Salcombe in Devon, England, when out of the corner of his eye he spotted what turned out to be a bronze sword lying exposed on the gravel bottom 6.5m below the surface.122 After taking the sword back to the shore he went out again with one of the beginners taking part in the swimming course. About 4 metres from where the first bronze sword was found, a second one was found lying on the gravel.123 On investigation these swords were dated to the 12th century BCE, only a few decades after the close of the ancient Near East’s Late Bronze Age.124

After a third bronze sword was found at the same location in October of that year, Baker along with Keith Muckelroy –a pioneer of maritime archaeology– performed a survey of the area the next year in the summer of 1978.125 More objects were found leading them to the tentative conclusion that their finds were from the remains of a Bronze Age shipwreck,126 though by the end of their final season in 1979 they’d had no success finding the wreck itself.127 In fact, the 1979 season bore only a single artefact – another bronze blade.128 Having run out of luck (and money), they ceased working at Moor Sand. And, for a few decades after that, the site lay undisturbed.

Erme Estuary

Just south of the tiny village of Mothecombe, half way between Salcombe and Plymouth on England’s southern coast, lies the beautiful Mothecombe beach. Flanked by small coppice-crowned cliffs, the small beach looks out over the tranquil Erme Estuary mouth and the wider Bigbury Bay. A more perfect childhood holiday spot could not be asked for.

If, however, you’re sailing a boat in the area, you’re less likely to be taking in the area’s natural beauty and more likely to be putting your mind to navigating its notoriously treacherous waters. In this idyllic spot many boats have been sent to Davey Jones’ Locker. The western side of the bay especially seems to have been designed to bring boats and their cargo to a swift and untimely end. A reef known as Mary’s Rock has claimed many ships.129

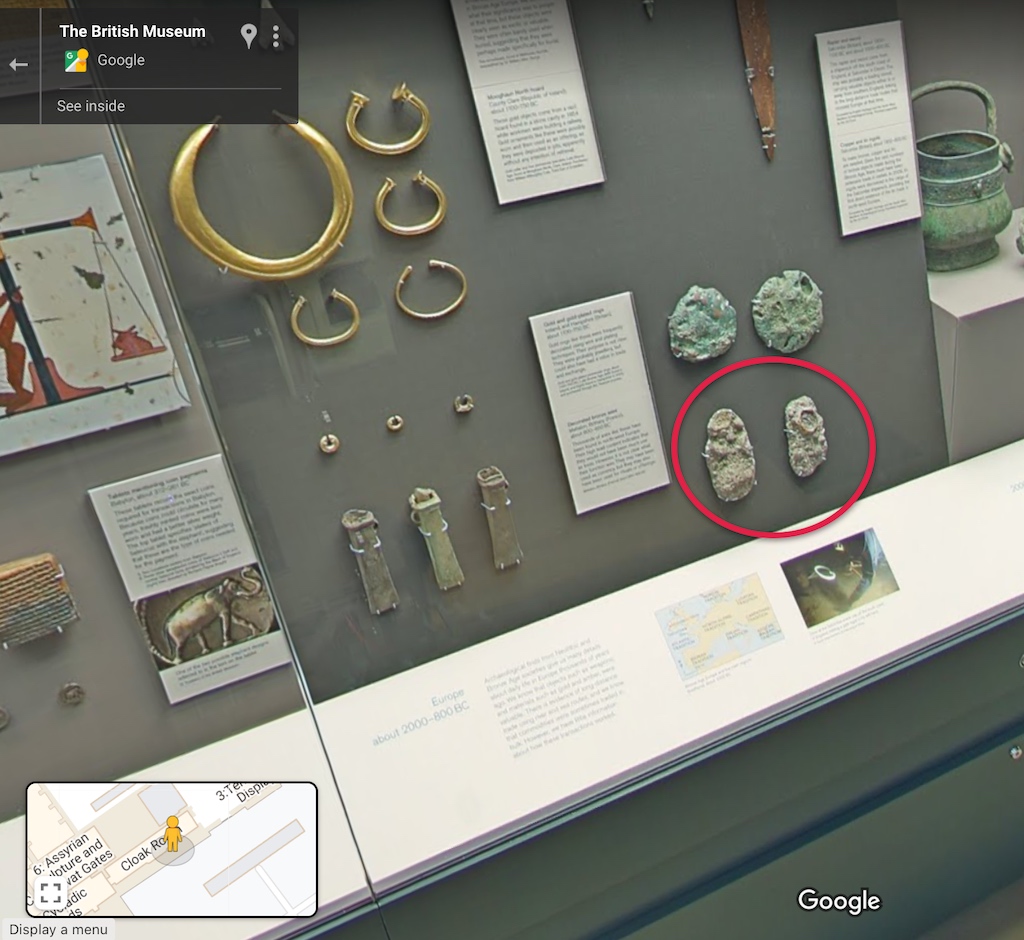

In 1990, more than 10 years after the expedition at Salcombe ended, a “cannon site”, i.e. a cannon on the sea bed indicating the location of a shipwreck, was reported as lying between Mary’s Rock and Mothecombe beach.

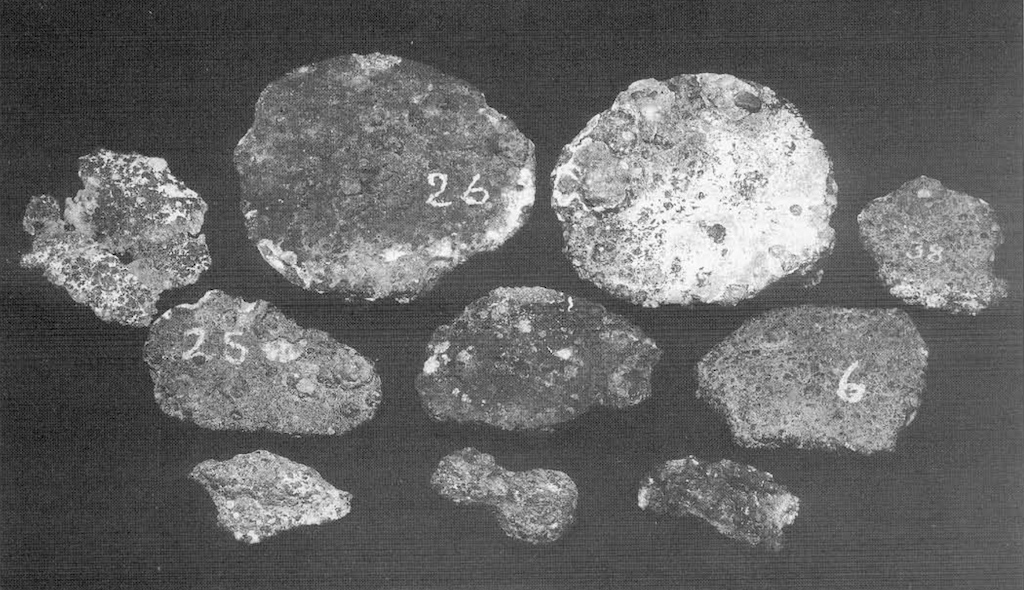

A team of divers from the South-West Archaeological Group investigated the site and found a number of iron guns strewn across the sea floor. In May 1991 the divers returned to survey the sea bed and found all manner of artefacts, evidently from numerous shipwrecks.130 They also found, between 8-10 metres below the surface, a load of tin ingots of all shapes and sizes weighing anywhere from less than a kilo to 13kg.131

In 1992 more survey work was performed, adding to the haul of tin ingots. Cannons, guns, rigging blocks, lead shot, crow bars, cannon balls, and even a Spanish bronze figurine dated to 500 CE were also found.132 During the 1993 season yet more tin ingots came to light, bringing the total to 42.133

Though the tin ingots proved difficult to date – Fox writes that they could have been produced anywhere between 500 BCE to 600 CE – there was no question where the ingots had come from: Cornwall.134

We now bring our attention back to Salcombe…

Back to Moor Sand

After a 17th century cannon was found on the sea floor a few hundred metres west of the Moor Sand site, the South West Maritime Archaeological Group (“SWMAG”) –the same group of divers from the South West Archaeological Group that had worked on the Erme Estuary site– began surveys in the area in 1992. Altogether 9 cannons were found at this location that came to be known as the “Salcombe Cannon Site”.135 In 1995 and 1997 they came across gold ingots, coins, and jewellery, amongst other artefacts.136

From 2004 onwards SWMAG began to find Bronze Age artefacts near the Moor Sand site – gold jewellery, bronze tools, and more bronze swords.137 A few years later they began to find tin ingots: in 2010 they found 29 bun-shaped tin ingots138, during the “extremely disappointing” 2011 they found only a small, round fragment of tin139, and in 2013 they found another 11 tin ingots; a grand total of 40 tin ingots.140

The final piece of the puzzle

With these tin ingots from England’s southern coast, we come back to the task of identifying the source that supplied tin to the Levant during the Late Bronze Age.

We saw earlier that lead and tin isotope ratios can be used to narrow down the source to one of,

- Erzgebirge

- Iberian Peninsula

- Cornwall

We’d also seen that we’d only be able to work out which of the above was the source by comparing the trace elements of the tin ingots from Hishuley Carmel, Kfar Samir North and South with those of tin ingots from the above regions.

In 2016 the final piece of the puzzle was published: an article containing the chemical analysis performed on 40 of the tin ingots from Moor Sand, and on 2 of the ingots from the Erme Estuary.141

Like the tin ingots found at Hishuley Carmel, Kfar Samir North & South, the tin ingots from Salcombe Moor Sand had very few impurities with little variation in chemical composition. This consistency was also true of their amounts of trace iron, lead, antimony, silver, arsenic, copper, indium, and bismuth.142

This was something scholars could work with.

Putting it all together

Berger et al, in their 2019 paper we referred to earlier, analysed this trace element data and compared it to the trace element data for the Israeli ingots. Here’s what they found:

European cassiterite mineralisations are rarely indium-rich as well, but a major exception seems to be the deposits in Cornwall/Devon, and especially those associated with the Carnmenellis and St. Agnes granites having cassiterites with high indium contents of more than 300 μg g-1. Interestingly, the Salcombe ingots found offshore the Devon coast exhibit indium contents similar to those of the Mediterranean ingots. If also antimony, lead and bismuth are considered in plotting a four-element diagram (Pb/Bi vs. Sb/In), many of the Israeli ingots and the piece from Mochlos match the British items.143

Also,

by including the trace element patterns of the Mediterranean tin ingots, the potential sources can be confined further. Because the elemental composition is quite similar to those of the Salcombe ingots, and the latter were certainly made from Cornish or Devonian tin ores, a British provenance of the tin from Israel is currently the most reasonable. The comparably high indium concentration in the ingots that is a typical feature of Cornish cassiterites might be the most helpful indication.144

Evidently, there’s a match – the amount of certain trace elements in the ingots found off Israel’s coast matches those found in the ingots found off England’s coast! With this development we can cross off two of the three options we had left:

ErzgebirgeIberian Peninsula- Cornwall

We have our source!

Based on all the previous analysis it seems pretty safe to agree with Berger et al when they write,

Cornish tin mines are the most likely suppliers for the 13th–12th centuries tin ingots from Israel”145

…specifically, the St Agnes and Carnmenellis regions of Cornwall due to the Indium match.

But…

Wait a second… didn’t we conclude that “The written sources tell us nothing useful”? Didn’t some of them point to a British, and even Cornish origin for tin? Yes, yes they did. Amid the noise, it seems there was a tiny bit of signal. The glimmer of some very dim memory can be seen in some of the ancient sources, but that’s really all it is. From the ancient sources we could well have concluded that the Levant’s Late Bronze Age source of tin was Spain. Or France. Or the Scilly Isles. Or near wherever Herodotus’ gold-guarding griffins were.

It’s the archaeology and chemical analysis of the artefacts that demonstrated that the Israeli tin ingots came from Cornwall, not jibber jabber from Diodorus Siculus. It’s science, not Strabo.146

Souvenirs from St Agnes, Cornwall

Cornwall’s tin mining heritage can be seen all over the county. Old tin mines dot the countryside, especially along the coast. The most famous are those that hug the region’s dramatic cliffs, e.g. Wheal Coates Mine:

The vast majority of the evidence of tin mining is from 1500 CE onwards; signs of earlier tin mining is sparse. The reason for this is due to the fact that until around 1500 CE, the tin ore was being extracted from alluvial deposits – it was simply lifted out of streams beds, or from just below the surface.147 Where tin had being mined from the edge of coastal outcrops, those outcrops have “eroded back considerably over the last three and a half thousand years and primitive workings may well have disappeared.”148 It’s therefore thought that “alluvial tin (cassiterite) was being mined on a much larger scale than the archaeological evidence would seem to suggest.”149

In Carew’s Survey of Cornwall, from 1602 (!), he describes how the “Tynners”, i.e. tin miners, found and extracted tin:

They discover these works, by certain Tynne-stones, lying on the face of the ground, which they term Shoad, as shed from the main Load, and made somewhat smooth and round, by the waters washing & wearing. Where the finding of these affordeth a tempting likelihood, the Tynners go to work, casting up trenches before them, in depth 5. or 6. foot more or less, as the loose ground went, & three or four in breadth, gathering up such Shoad, as this turning of the earth doth offer to the sight. If any river thwart them, and that they resolve to search his bed, he is trained by a new channel from his former course. This yealdeth a speedy and gainful recompense to the adventurers of the search, but I hold it little benefit to the owners of the soil.150

This was the same method employed “several millennia before”151 – as we saw earlier Diodorus describes a very similar method. Indeed the tin streams created by this approach are “so widespread in Cornwall that it is pointless to list them all.”152

We could look at any number of examples of ancient Cornish tin mining sites to round out the picture we’ve been looking at in this post, but there are none more idyllic than Trevellas Coombe in the St Agnes area of Cornwall – the same area identified by Berger et al as one of the English sources of tin used in the southern Levant during the Late Bronze Age.153

Through this seemingly inconsequential, short, little valley runs the tin ore-bearing Trevellas Coombe stream that has attracted miners since the Bronze Age.

A number of old, crumbling and disused 18th century engine pumping houses line the stream, never allowing the visitor to forget the tin that “overfloweth England, watereth Christendom, and is [channelled] to a great part of the world besides.”154

Nestled at the bottom of the valley, less than 500m from where it meets the sea at Trevellas Cove, sits the Blue Hills tin mining museum, owned and run by the Wills Family. They have been producing tin from cassiterite found in the local area since the 1960s – the only British tin smelting company still in operation. A wander around the outdoor and indoor museum is a lovely way to spend a sunny morning – perfect dad material.

As we come to the conclusion of this excessively long post, let’s exit through their gift shop. It’s a rather unusual affair in that they make the tin objects for sale right in front of your very eyes. They heat the tin, pour it into moulds, and chat with visitors as it cools.

When I visited I picked up a numbered tin ingot, and for my overenthusiasm also received a small piece of 70% pure local cassiterite.

It’s funny to think that on my desk, guarded by Mandalorian Lego, sits a tin ingot made from St Agnes cassiterite sharing the same lead and tin isotope ratios and trace elements as the ingots that made their way from the same place to the Late Bronze Age southern Levant.

Further reading

- Ehud Galili, Noel Gale, and Baruch Rosen, “Bronze Age Metal Cargoes off the Israeli Coast,” Skyllis: Zeitschrift für Unterwasserarchäologie, Vol. 11, No. 2 (2011): 71.

- Daniel Berger, Jeffrey S. Soles, Alessandra R. Giumlia-Mair, Gerhard Brügmann, Ehud Galili, Nicole Lockhoff, Ernst Pernicka, “Isotope systematics and chemical composition of tin ingots from Mochlos (Crete) and other Late Bronze Age sites in the eastern Mediterranean Sea: An ultimate key to tin provenance?,” PloS one (June), Vol. 14, No. 6 (2019).

- Roger. D. Penhallurick, Tin in Antiquity: Its mining and trade throughout the ancient world with particular reference to Cornwall (Maney Publishing, 1986).

Featured image

Mothecombe Beach on the Erme Estuary, England, taken on my September 2020 holiday.

Footnotes

-

Note that the Bronze Age, like the Stone and Iron that it came between, began and ended at different times depending on the location. E.g. the England, the Bronze Age began in 2100 BCE and ended in 750 BCE – considerably later than it did in the Near East. ↩

-

“Bronze is first introduced to the region in the MB I, replacing copper as the primary metal used.” Anson F. Rainey and R. Steven Notley, The Sacred Bridge: Carta’s Atlas of the Biblical World, Second Emended & Enhanced Edition. (Jerusalem, Israel: Carta Jerusalem, 2014), 60. ↩

-

“In MB IIA, bronze replaced copper, which had been almost the only metal in use for tools and weapons since the Chalcolithic period. Bronze is an alloy of copper with 5–10 percent tin.” Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible 10,000-586 B.C.E. (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 1990), 184. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Carol Bell, “The Merchants of Ugarit: Oligarchs of the Late Bronze Age Trade in Metals?,” in Eastern Mediterranean Metallurgy and Metalwork in the Second Millennium BC, ed. Vasiliki Kassianidou and George Papasavvas (Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books, 2012), 180. ↩

-

Ibid., 180-181. ↩

-

We’ve written about one of them on this site before – the bull statuette from the Bull Site. ↩

-

Or 370, or 470, depending on the manuscript. See William H. C. Propp, Exodus 19–40: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, vol. 2A, Anchor Yale Bible (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2008), 652. ↩

-

Peter Enns, Exodus, The NIV Application Commentary (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2000), 549. ↩

-

How to understand the reference to Tarshish is a question that’s attracted a mountain of speculation, especially amongst certain Premillennialist Christian denominations. ↩

-

David J. A. Clines, ed., The Dictionary of Classical Hebrew (Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press; Sheffield Phoenix Press, 1993–2011), 95. ↩

-

Paula M. McNutt, The Forging of Israel: Iron Technology, Symbolism, and Tradition in Ancient Society (Sheffield Academic Press, 1990), 105-106. ↩

-

Ludwig Koehler et al., The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1994–2000), 110. ↩

-

“It is astonishing, that the practice of imparting hardness to copper, by alloying it with a certain proportion of tin, sufficient for sword-blades, and other cutting instruments, should have been so generally followed by the ancients, notwithstanding the want of tin-mines.” Christopher Hawkins, Observations on the Tin Trade of the Ancients in Cornwall and on the Ictis of Diodorus Siculus (1811), 11-12. Available here. ↩

-

“Copper ores in the Arabah were exploited in the Late Bronze Age only from the beginning of the thirteenth century B.C.E., when the Egyptians established mines at Timna.” Mazar 1990, op. cit., 265. ↩

-

“Cyprus was the main source of copper throughout the eastern Mediterranean during the Late Bronze Age. Oxhide-shaped copper ingots originating in Cyprus were exported to all parts of the Mediterranean…” Mazar 1990, op. cit., 264. ↩

-

George Papasavvas, “Profusion of Cypriot copper abroad, dearth of bronzes at home: a paradox in Late Bronze Age Cyprus,” in Eastern Mediterranean Metallurgy and Metalwork in the Second Millennium BC, ed. Vasiliki Kassianidou and George Papasavvas (Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books, 2012), 117. ↩

-

“The name occurs frequently in the 14th century B.C., especially in the correspondence between the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten and the king of Alashia, which also refers to a land that produced copper.” John McRay, “Cyprus (Place),” ed. David Noel Freedman, The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 1228. ↩

-

William L. Moran, The Amarna Letters, English-language ed. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992), 107. ↩

-

A. Livingstone, “Nergal,” ed. Karel van der Toorn, Bob Becking, and Pieter W. van der Horst, Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (Leiden; Boston; Köln; Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge: Brill; Eerdmans, 1999), 622. ↩

-

Norman De Garis Davies, The Rock Cut Tombs of El Amarna (1903), Plate XXXI. ↩

-

Figure 31.6.34 in Charles K. Wilson, Egyptian Wall Paintings: The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Collection of Facsimiles (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1983), 87. Colour version from the Metropolitan Museum of Art website: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/544617 ↩

-

Ehud Galili, Noel Gale, and Baruch Rosen, “Bronze Age Metal Cargoes off the Israeli Coast,” Skyllis: Zeitschrift für Unterwasserarchäologie, Vol. 11, No. 2 (2011): 71. ↩

-

Theodore A. Wertime, “The Beginnings of Metallurgy: A New Look,” Science (November), Vol. 182, No. 4115 (1973): 884. ↩

-

Gerhard Brügmann, Daniel Berger, Carolin Frank, Janeta Marahrens, Bianka Nessel, and Ernst Pernicka, “Tin Isotope Fingerprints of Ore Deposits and Ancient Bronze,” in The Tinworking Landscape of Dartmoor in a European Context – Prehistory to 20th Century: Papers Presented at a Conference in Tavistock, Devon, 6-11 May 2016 to Celebrate the 25th Anniversary of the DTRG, ed. Phil Newman (Dartmoor Tinworking Research Group, 2017), 112. ↩

-

Friedrich Begemann and Konrad Kallas and Sigrid Schmitt-Strecker and Ernst Pernicka, “Tracing ancient tin via isotope analyses,” The Beginnings of Metallurgy. Der Anschnitt, Beiheft 9,(1999), 277. ↩

-

Mazar 1990, op. cit., 184. ↩

-

Benjamin J. Noonan, “Trade and Commerce,” ed. John D. Barry et al., The Lexham Bible Dictionary (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016). ↩

-

Avraham Negev, The Archaeological Encyclopedia of the Holy Land (New York: Prentice Hall Press, 1990). ↩

-

Kai Kaniuth, “The Metallurgy of the Late Bronze Age Sapalli Culture (Southern Uzbekistan) and its Implications for the Tin Question,” Iranica Antiqua, Vol. 42 (2007): 24-25. ↩

-

Robert Maddin and Tamara Stech Wheeler and James D. Muhly, “Tin in the Ancient Near East: Old Questions and New Finds,” Expedition, Vol. 9, No. 2 (1977): 38. ↩

-

Ehud Galili and Noel Gale and Baruch Rosen, “A Late Bronze Age Shipwreck with a Metal Cargo from Hishuley Carmel, Israel,” The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology (March), Vol. 42, No. 1 (2012), 20. ↩

-

Literally, “of tin”. See Franco Montanari, ed. Madeleine Goh and Chad Schroeder, The Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2015). ↩

-

Herodotus, with an English Translation by A. D. Godley, ed. A. D. Godley (Medford, MA: Harvard University Press, 1920). ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Donald Lateiner, “Historiography: Greco-Roman Historiography,” ed. David Noel Freedman, The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 214. ↩

-

“Some confusion between tin and lead appears to have occurred in the ancient world… Without doubt Pliny’s plumbum candidum was tin and his plumbum nigrum lead.” P. G. Harrison, “Tin – the element,” in Chemistry of Tin, ed. Peter J. Smith (Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business Media, 1998), 2. ↩

-

Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, ed. John Bostock (Medford, MA: Taylor and Francis, Red Lion Court, Fleet Street, 1855), 1352. ↩

-

For an in depth discussion about the location of Ictis, see C. Hawkes, “Ictis disentangled, and the British tin trade,” Oxford Journal of Archaeology (July), Vol. 3, No. 2 (1984): 211-233. ↩

-

Johan C. Thom, “Stoicism,” Dictionary of New Testament Background: A Compendium of Contemporary Biblical Scholarship (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000), 1140. ↩

-

Strabo, The Geography of Strabo. Literally Translated, with Notes, in Three Volumes., ed. H. C. Hamilton (Medford, MA: George Bell & Sons, 1903), 221. ↩

-

Booth, The Historical Library of Diodorus the Sicilian, Volume 1 (London: W. McDowell, 1814), 309. ↩

-

Ibid., 310-311. ↩

-

William Smith, “Bele’rium” in Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (London: Walton and Maberly, 1854). ↩

-

Strabo 1903, op. cit., 181. ↩

-

Ibid., 262–263. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Pliny 1855, op. cit., 2225. ↩

-

Ibid., 1367. ↩

-

James M. Scott, “Geographical Perspectives in Late Antiquity,” Dictionary of New Testament Background: A Compendium of Contemporary Biblical Scholarship (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2000), 412. ↩

-

Yumna Khan, A Commentary on Dionysius of Alexandria’s Guide to the Inhabited World, 174-382 (2002), 235. ↩

-

For way more info about this legend than you really want to read, take a look at A. W. Smith, “And Did those Feet…?’ the ‘Legend’ of Christ’s Visit to Britain,” Folklore (January), Vol. 100, No. 1 (1989): 63-83. ↩

-

Antonia Gransden, “The Growth of the Glastonbury Traditions and Legends in the Twelfth Century,” Journal of Ecclesiastical History (October), Vol. 27, No. 4 (1976): 358. ↩

-

Rising sea levels have caused what was once one large island to be divided into the many Scilly Isles that exist today. However, their number has seen little change since the time period we’re interested in (1550-1200 BCE) until today so for our purposes we can discount the changes in sea level. See Peter Marshall and Charlie Johns, “The Past as the Key to the Future,” Historic England Research (April), Issue 8, (2018): 62-63. It was around 3000-2000 BCE that the islands were separated by rising tides. See Barnett et al., “Nonlinear landscape and cultural response to sea-level rise,” Science Advances (November), Vol. 6, No. 45. (2020): 1-10. ↩

-

Roger. D. Penhallurick, Tin in Antiquity: Its mining and trade throughout the ancient world with particular reference to Cornwall (Maney Publishing, 1986), 120. ↩

-

For details on the tiny amounts of Cassiteride found in the Scilly Isles of Trestco, White Island, and Bryher, see, J. B. Grant and C. W. E. H. Smith, “Evidence of Tin and Tungsten Mineralisation in the Isles of Scilly,” Geoscience in South-West England, Vol. 13, (2012): 65-70. ↩

-

Penhallurick 1986, op. cit., 120-122. ↩

-

Mark Woolmer, Ancient Phoenicia: an Introduction (Bristol Classical Press, 2011), 46-49 ↩

-

Penhallurick 1986, op. cit., 123-131. ↩

-

Ibid, 123. ↩

-

Penhallurick 1986, op. cit., 123. ↩

-

Beatriz Comendador Rey, Emmanuelle Meunier, Elin Figueiredo, Aaron Lackinger, Joao Fonte, Cristina Fernanz, Alexandre Lima, Jose Mirao, and Rui J. C. Silva, “Northwestern Iberian Tin Mining from Bronze Age to Modern Times: an overview,” in The Tinworking Landscape of Dartmoor in a European Context – Prehistory to 20th Century: Papers Presented at a Conference in Tavistock, Devon, 6-11 May 2016 to Celebrate the 25th Anniversary of the DTRG, ed. Phil Newman (Dartmoor Tinworking Research Group, 2017), 135. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Shelley Wachsmann, Richard K. Dunn, John R. Hale, Robert L. Hohlfelder, Lawrence B. Conyers Eileen G. Ernenwein, Payson Sheets, Maria Luisa Pienheiro Blot, Filipe Castro, and Dan Davis, “The Palaeo‐Environmental Contexts of Three Possible Phoenician Anchorages in Portugal,” The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology (September), Vol. 38, No. 2 (2009), 227-228. ↩

-

“Tarshish” in scripture is often identified, somewhat tenuously, with the “Tartessian” people. E.g. “The name Tarshish, then, is Iberian or ‘Tartessian’”. E. Lipiflski, “תַּרְשִׁישׁ,” ed. G. Johannes Botterweck, Helmer Ringgren, and Heinz-Josef Fabry, trans. David E. Green, Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2006), 792. See also Brigette Treumann-Watkins, “Phoenicians in Spain,” Biblical Archaeologist: Volume 55 (American Schools of Oriental Research, 1992), 32–33. ↩

-

Alonso Rodríguez Díaz, David M. Duque Espino, Ignacio Pavón, and Moisés Ponce de León, “La explotación tartésica de la casiterita entre los ríos Tajo y Guadiana: San Cristóbal de Logrosán (Cáceres),” Trabajos de Prehistoria (June), Vol. 70, No. 1 (2013): 102. ↩

-

“La difficulté disparaît, et le témoignagede Festus Avienus reprend toute sa valeur lorsque, sous la conduite de Léon Maître, dont les remarquables études archéologiques ont été réunies en un volume intitulé: Les villes disparues des Namnètes on reconstitue les contours du littoral de la Basse Loire, tels qu’ils se présentaient avant le récent colmatage du golfe où s’étalent aujourd’hui, au Nord de Dönges et de Saint-Nazaire, les prairies humides du cours inférieur du Brivé, et, plus loin vers l’intérieurdes terres, les marais de la Brière. Avant ce comblement qui ne s’est achevé que postérieurement aux temps gallo-romains, ce golfe, parsemé d’îles rocheuses, était noyé sous des eaux fluviales qu’influençait le mouvementdes marées. Il communiquait avec la mer par un large détroit qui est aujourd’hui, entre Paimbœuf et Saint-Nazaire, l’embouchure de la Loire. Les abords, les rives et les îles de l’ancien golfe furent, à l’époque du bronze, animés par le commerce et l’industrie. Des fonderies nombreuses, dont les restes laissent reconnaître des aménagements semblables à ceux des ateliers ibériques de même âge, y traitaient l’étain et le plomb argentifère, extraits dans le proche voisinage. La densité et la qualité des trouvailles attestent la présence en ces lieux, à cette époque, d’une population nombreuse et prospère.” R. Dion, “Le problème des Cassitérides,” Latomus (July-September), Vol. 11, No. 3 (1952): 309. ↩

-

He cites Léon Maître, Les Villes Disparues de la Loire-Inférieure: Tome I (1886), but as far as I can make out (my French is rustier than Tow Mater) it doesn’t contain a passage that backs up his claim. ↩

-

Penhalluric 1986, op. cit., 128-129. ↩

-

“…our synthesis shows that alluvial [tin] exploitations have existed from Bronze Age to Middle Age.” Cécile Le Carlier de Veslud and Céline Siepi and Christian Le Carlier de Veslud “Tin Production in Brittany (France): A Rich Area Exploited since the Bronze Age,” In Archaeometallurgy in Europe IV (Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas, 2017), 96. ↩

-

Ibid., 99. ↩

-

Ibid., 101. ↩

-

For a masterclass in ad-hominem, special pleading, and shifting the burden of proof, have a read of George Smith, The Cassiterides: An Inquiry into the Commercial Operations of the Phoenicians in Western Europe with Particular Reference to the British Tin Trade (London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts, 1863),152-154. Here’s how he concludes his book: “If it is maintained that tin was not brought from Britain, we respectfully ask, Whence was it brought? If Phoenician ships did not then visit our shores for the purchase of tin, what maritime people did? Was the metal taken a thousand years before our era from Cornwall to the coast of Prance in British coracles, made of osiers and skins, or by what other means? How was this commodity transferred to the mouths of the Rhone hundreds of years before Marseilles and Narbo were built? We propound these questions with great respect and seriousness. We will venture to say that we have stated a means by which this market, in the earliest ages, might have been supplied. That the Phoenicians traded to Gades is an undoubted fact; and, this being admitted, the possibility of their reaching Cornwall cannot be denied. If, then, this is deemed improbable and incredible, let us have some probable and credible means exhibited, by which the metal was taken to the East. We repeat that this ought to be done. When men who have established a world-wide reputation for learning, and those who conduct periodicals which are circulated over the globe, repudiate what has been long and widely held as an undoubted truth, we have a right to ask for a substitute to fill up the chasm and restore unity and completeness to our knowledge of the subject. In a case like this, when the old popular tradition of Phoenician intercourse with Britain is denied, the world is entitled to something more from such quarters than an uninstructive expression of scepticism,—a barren declaration of disbelief. The world has outlived the day when the dictum of the learned could create or annihilate an article of popular faith. It is now happily essential that facts and reasons be given, if old errors are to be exploded, or new truths fixed in the public mind. When this is done, we shall be ready with frankness and candour to correct our judgment on this subject; but till then, no mere expressions of doubt or disbelief, however high the source whence they emanate, will shake our faith in “conclusions” which we believe to be founded on legitimate historical evidence, and worthy to be regarded as established truths.” ↩

-