Shamgar son of Anath

Deborah, Gideon, and Samson were judges of Israel that we hear plenty about. The record of their deeds spans numerous chapters. In the long hallways of history their exploits are displayed on sweeping tapestries spanning many metres. But hidden away in a dark corner poor Shamgar gets only a postage stamp: a single verse.

Jdg 3:31 After [Ehud] came Shamgar son of Anath, who killed six hundred of the Philistines with an oxgoad. He too delivered Israel.1

That’s it, and it’s not much. We tend to skip right over it when we read the book. But when we zoom in on this postage stamp we’ll discover an altogether unconventional image – there’s plenty in it, and it’s worth spending the time taking in every square millimetre.

After Ehud

Though the book of Judges contains poetry, hyperbole, and theological slant, it is also acknowledged to preserve a fair few historical details.2 The most celebrated example of a text in Judges that does this is the Song of Deborah. It is widely acknowledged to be one of the earliest sections of scripture; an example of a composition of Early Yahwistic Poetry, dated by some to 1100 BCE3, only about a century after the beginning of the archaeologically-attested Israelite settlement.4

When we read through Deborah’s song we come across this:

Jdg 5:6 In the days of Shamgar son of Anath, in the days of Jael, caravans ceased and travelers kept to the byways.

This does not prove the existence of Shamgar by any means. But, it does show that the tradition of a “Shamgar son of Anath” goes back a long way. A very long way, close to the beginning of Israelite history in the Canaanite highlands.

If Deborah’s song was composed in around 1100 BCE, then anything it mentions must predate it, including Shamgar.

Shamgar

What about his name? If you search through the Hebrew Bible you won’t find anyone else named Shamgar. If it were a Hebrew name, we’d probably see it used a few times. But we don’t.

It turns out that Shamgar is non-Semitic, and most likely Hurrian.5 Toward the end of the Middle Bronze Age (sometime around 1550 BCE, more than 200 years before the Israelite settlement) there was an influx of Hurrians into Canaan, explaining how names like Shamgar arrived in the area.6

So, based solely on his name, Shamgar most likely was not a Hebrew.

Son of Anath

Though Shamgar is not a semitic name, Anath definitely is. Anath is the name of an adolescent warrior goddess in the Canaanite pantheon. Unlike other Canaanite gods like El, Baal, and Asherah, we don’t find Anath mentioned in the Hebrew Bible much. Just here, and as part of place names like Beth-Anath (mentioned in Jos 19:38 & Jdg 1:33).7

We know a fair bit about the goddess Anath from ancient sources. Here is an excerpt from the Baal Cycle8 that describes her mode of fighting:

And look! Anat fights in the valley, battles between the two towns. She fights the people of the se[a] shore, strikes the populace of the su[nr]ise. Under her, like balls, are hea[ds,] above her, like locusts, hands, like locusts, heaps of warrior-hands. She fixes heads to her back, fastens hands to her belt. Knee-deep she glea[n]s in warrior-blood, neck-deep in the gor[e] of soldiers. With a club she drives away captives, with her bow-string, the foe. – KTU 1.3:2:5–16

She was not a goddess to be messed with.

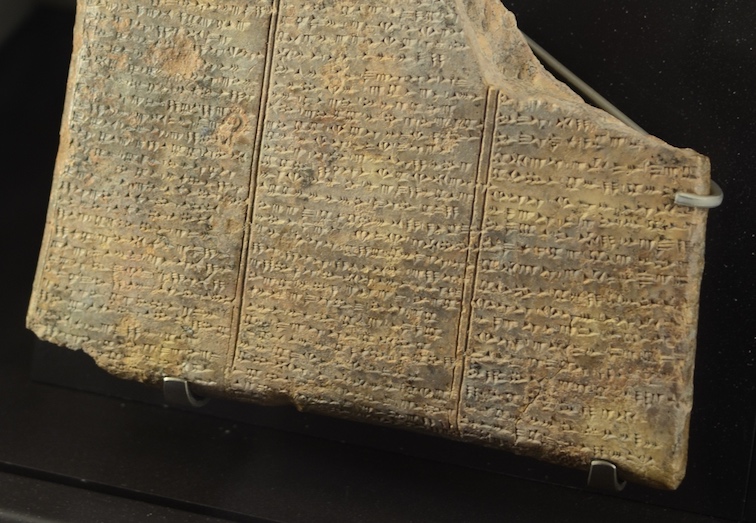

Anath was chosen to be the matron goddess of warrior bands in Canaan. Discovered between 1954 and 1980, arrowheads dated to 1100-1050 BCE from the area of Bethlehem came to light.9 They were inscribed with the following formula: The servant of [insert god here, e.g. Ishtar or Baal], or [insert name here] son of [insert god here]. These arrowheads belonged to warrior groups or guilds active in the Canaanite highlands.

Fascinatingly, one of them had this inscription:

Abd-Labīʾt Bin-ʿAnat10

What do we have here? Someone Son of Anath. This discovery shone significant light on Judges 3:31. Instead of imagining that Anath was the name of Shamgar’s mother, we now can be pretty confident that Shamgar, the warrior credited with killing many philistines, was a Canaanite member of a Canaanite warrior gang roaming the highlands administering justice like some sort of Conan the Barbarian figure.

600 Philistines

The final detail to look at is just how many Philistines Shamgar fought. Like many other numbers in the earlier narratives, this one is not to be taken at face value; “600” had a specific meaning in this period in the ancient Near East; it was a term meaning a “good sized military unit.”11 We see the term used elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible:

Jdg 18:11–12 Six hundred men of the Danite clan, armed with weapons of war, set out from Zorah and Eshtaol, and went up and encamped at Kiriath-jearim in Judah.

Jdg 20:47 But six hundred turned and fled toward the wilderness to the rock of Rimmon, and remained at the rock of Rimmon for four months.

1 Sa 27:2 David set out and went over, he and the six hundred men who were with him, to King Achish son of Maoch of Gath.

So, 600 is figurative. This does nothing to detract from Shamgar’s prowess as a fighter – the tale of taking on an entire Philistine unit would have made excellent fireside entertainment in the Israelite settlements.

Summary

So, what do we have in Judges 3:31? This apparent footnote at the end of the Ehud narrative contains an ancient tradition – Shamgar, a Canaanite member of a warrior clan dedicated to Anat the Canaanite warrior goddess, is credited with delivering Israel by defeating a Philistine military unit.

Not all deliverers of Israel were Israelite. Sometimes they were just Canaanites with a common enemy.

Further reading

- P. L. Day, “Anat,” ed. Karel van der Toorn, Bob Becking, and Pieter W. van der Horst, Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (Leiden; Boston; Köln; Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge: Brill; Eerdmans, 1999), 36–43.

- Gordon Hamilton, “The El Khadr Arrowheads”, William W. Hallo and K. Lawson Younger, Context of Scripture (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2000), 221–222.

- Gregory Mobley, The Empty Men: The Heroic Tradition of Ancient Israel (New York: Doubleday, 2005), 27–31.

- The El-Khadr arrowhead at the Israel Museum

Featured Image

Solomon’s Pools in the El Khadr area of Bethlehem, the location of the discovery of the El-Khadr arrowheads.

Footnotes

-

Unless otherwise noted all scripture quotations are from the New Revised Standard Version (Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1989) ↩

-

See K. A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2006), 199–239 for a defence of the historicity of the events recorded in Judges. See also Gregory Mobley’s The Empty Men: The Heroic Tradition of Ancient Israel (New York: Doubleday, 2005) serves as an excellent introduction to some of the various critical issues in the book of Judges. ↩

-

“…the Song of Deborah, a victory hymn, the occasion of which is known, and the approximate date quite certain, i.e., ca. 1100 B.C… This victory hymn, one of the oldest and most dramatic specimens of early Yahwistic poetry, belongs to the same general period as the other great victory songs so far known from the ancient world: the hymn of Rameses II after the battle with the Hittites at Kadesh, the poems describing the victory of Merneptah over the Libyans, and Rameses III over the Sea Peoples, and the victory hymn of Tukulti-Ninurta I, after his defeat of the Cossaeans. The Song of Deborah is also to be grouped with the Song of Miriam (Ex. 15) celebrating the destruction of Pharaoh’s host in the Reed Sea.” Frank Moore Cross Jr and David Noel Freedman, Studies in Ancient Yahwistic Poetry (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.; Livonia, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.; Dove Booksellers, 1997), 3. ↩

-

“Intensive archaeological surface surveys revealed an entirely new settlement pattern in Iron Age I. Hundreds of new small sites were inhabited in the mountainous areas of the Upper and Lower Galilee, in the hills of Samaria and Ephraim, in Benjamin, in the northern Negev, and in parts of central and northern Transjordan. Much of this activity can be related to Israelite tribes, though the ethnic attribution in some of these regions is still questionable.” Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible 10,000-586 B.C.E. (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 1990), 334. ↩

-

B. Maisler (1934) Shamgar Ben ‘Anat, Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 66:4, 192-194. ↩

-

“Northern Syria suffered from Hittite raids at the end of the seventeenth century B.C.E.; the raids caused the collapse of the great kingdom of Yamhad, centered at Aleppo. This collapse was followed by an interruption in the flourishing West Semitic civilization of northern Syria and by an influx of Hurrian population from northern Mesopotamia into Syria; a thinner stream of these people advanced farther to the south and appeared in Palestine. Thus some change in the ethnic composition of Canaan occurred and was to become an important factor in the following period.” Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible 10,000-586 B.C.E. (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 1990), 226. ↩

-

For the association of Anath to Beth-Anath see P. L. Day, “Anat,” ed. Karel van der Toorn, Bob Becking, and Pieter W. van der Horst, Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible (Leiden; Boston; Köln; Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge: Brill; Eerdmans, 1999), 42. Beth-Anath had previously been associated with the modern town of Aynata, but this is no lonver accepted: “The identification with ‘Aynāta, suggested in the early phases of modern Eretz-Israel scholarship, is no longer accepted today, as the location does not fit the biblical data (52 n. 12).” Yoel Elitzur, Ancient Place Names in the Holy Land: Preservation and History (Jerusalem; Indiana: The Hebrew University Magnes Press; Eisenbrauns, 2004), 374. ↩

-

Mark S. Smith and Simon B. Parker, Ugaritic Narrative Poetry (vol. 9; Writings from the ancient world; Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1997), 107–108. ↩

-

“These five arrowheads, inscribed with Old Canaanite alphabetic letters, were found near Bethlehem and published between 1954 and 1980. Their weight and size, between 9.5 and 10.5 cm, fall within normal parameters for arrowheads used for practical purposes. Dating to ca 1100–1050 BCE, these inscriptions provide witness both to literacy and goddess religion in Palestine during the late second millennium.” Gordon Hamilton, “The El Khadr Arrowheads”, William W. Hallo and K. Lawson Younger, Context of Scripture (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2000), 221–222. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Jack M. Sasson, Judges 1–12: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (ed. John J. Collins; vol. 6D; Anchor Yale Bible; New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2014), 244–245. ↩