Joshua 10 and 11: Genre and Annihilation

In the previous post we looked at some features that we saw were common to both Joshua 10 and 11. We concluded that those features mark the chapters out as being something quite different to ordinary war reports or historical narrative. Instead of military history we found two highly formulaic accounts that follow a definite and distinct pattern. In the next few posts we’ll look at what these features tell us about the genre of these chapters by investigating comparative literature.

The features we noted were:

- Language of annihilation

- Repetitive and redundant language

- Hyperbole

- Common narrative structure

- Focus on the leader

It turns out that all the features we’ve seen are the defining characteristics of what are known as “Ancient Conquest Accounts”. History is littered with these accounts. They’ve been dug up by archaeologists, translated by language scholars, and interpreted by historians.

So, let’s begin our investigation of ancient Near Eastern extra-biblical comparative literature to see if it can shed some light on the first of the features we saw in Joshua 10 and 11; the language of Annihilation.

Language of Annihilation

As we’ve previously seen, both Joshua 10 and 11 claim that Canaan’s native population was completely wiped out, down to the last person. We’ve also previously pointed out that when taken at face value these claims are contradicted by many other statements elsewhere in Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings, never mind the archaeological record. Here are the verses we looked at:

Jos 10:40 So Joshua defeated the whole land, the hill country and the Negeb and the lowland and the slopes, and all their kings; he left no one remaining, but utterly destroyed all that breathed, as the LORD God of Israel commanded.1

Jos 11:14 All the spoil of these towns, and the livestock, the Israelites took for their booty; but all the people they struck down with the edge of the sword, until they had destroyed them, and they did not leave any who breathed.

That’s definitely the language of annihilation.

Our first bit of comparative literature is the Merneptah Stele. This inscription documenting Pharaoh Merneptah’s campaign in the Levant is well known to those who are interested in Israelite origins as it contains the earliest reference to a people called Israel. It was discovered in 1896 in Thebes by Sir Flinders Petrie and now resides in the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities in Cairo.

Here’s what it has to say about Israel:

The princes are prostrate, saying: “Mercy!” Not one raises his head among the Nine Bows. Desolation is for Tehenu; Hatti is pacified; Plundered is the Canaan with every evil; Carried off is Ashkelon; seized upon is Gezer; Yanoam is made as that which does not exist; Israel is laid waste, his seed is not; Hurru is become a widow for Egypt! All lands together, they are pacified; Everyone who was restless, he has been bound by the King of Upper and Lower Egypt.2

Pharaoh Merneptah seems to be claiming that he’d completely wiped out the Israelites.

But, it’s pretty obvious that Pharaoh Merneptah didn’t annihilate the Israelites – they’re mentioned in the Mesha Stele (dated ~835 BCE)3, never mind the biblical text.

So why did Pharaoh Merneptah have that written about him if it wasn’t true? Why include a claim that he’d annihilated a group that he hadn’t really annihilated at all? After all, wouldn’t any Egyptian capable of reading the stele think, “What is this nonsense? I saw loads of Israelites on my last boating holiday on the Sea of Galilee! I hope I don’t get thrown to the crocodiles for saying it, but, Pharaoh Merneptah’s a lying little…”

It would never have crossed the average Egyptian’s mind to read these sorts of texts in that way. Claims of annihilation were ideological and figurative statements showing that the Pharaoh had restored order after their enemies had created chaos, not actual records of the extinction of an entire people group.4

Apparent claims of annihilation weren’t unique to Egyptian conquest accounts; they can be found all over the ancient Near East. For another example we can look to the annals of the Hittite king Mursili II. He writes:

I made Mt. Asharpaya empty (of humanity). I made the mountains of Tarikarimu empty (of humanity).5

More annihilation. Again, it didn’t happen. It’s just how they wrote their conquest accounts.

Is it a surprise to find this sort of language in Joshua 10 and 11? If we are surprised then we shouldn’t be. In fact, what should be surprising is if we didn’t find the language of annihilation. Why? Because conquest accounts were written this way across the ancient Near East, from Thebes to Hattusa to Nineveh. Kings from all over described some of their victories as annihilations of their enemies; but rarely were their enemies actually annihilated.

So, to come back to our chapters, it’s clear that the Israelites wrote their conquest accounts just like everyone else.

Time for one final example – there are loads so we’ve limited ourselves to just a few in this post…

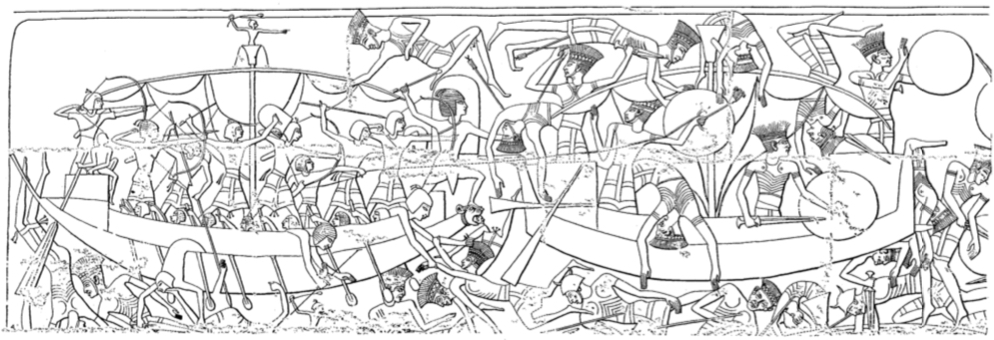

In Rameses III’s account of his “War Against the Peoples of the Sea” account recorded in relief on the walls of his mortuary temple of Medinet Habu, he describes the end result of his enemies:

Those who reached my frontier, their seed is not, their heart and their soul are finished forever and ever.6

These enemies were a collection of peoples known as the “Sea People” including the Peleset, the Israelites’ future enemy, the Philistines. Rameses III claimed that he’d annihilated them, but in later records of his we find that he’d actually not annihilated them, but used them as mercenaries and settled them in Gaza, Ashkelon, and Ashdod.7

Here’s what he had written in what is known today as Papyrus Harris:

I slew the Denyen in their islands, while the Tjeker and the Philistines were made ashes. The Sherden and the Weshesh of the Sea were made nonexistent, captured all together and brought in captivity to Egypt like the sands of the shore. I settled them in strongholds, bound in my name. Their military classes were as numerous as hundred-thousands. I assigned portions for them all with clothing and provisions from the treasuries and granaries every year.8

So which is it? Did he annihilate them? Or did he settle them and use them as mercenaries? The answer is clearly the latter, as archaeological evidence demonstrates.9

So, the language of annihilation that we find in Joshua 10 and 11 that didn’t seem to fit with anything else we read in Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings actually fits right into the genre of the age. The language of annihilation is what we should expect to find in an ancient conquest account, so it’s no surprise to find Joshua 10 and 11 featuring it.

We should also bear in mind that though annihilation is a feature of these texts, it doesn’t mean that annihilation ever happened. It was just part of the genre…

…rather like this:

No one reading this example of sports journalism would even think that Germans visiting Brazil in 2014 actually annihilated their host nation; it doesn’t cross our minds to think that’s what the article’s author meant. Why? Because we know we’re reading sports journalism. We know the genre; we know what to expect, and we know how to interpret it. And all of that is completely subconscious.

In that respect ancient conquest accounts (and all ancient literature) are no different – they’re written in a specific genre that makes use of the language of annihilation, a feature that was never intended to be taken at face value.

So, did Joshua annihilate the Canaanites? No. Judges, Samuel, Kings, the archaeological evidence, and the ancient conquest account genre of Joshua 10 and 11 speak with one voice: there was no annihilation.

Now that we’ve seen that the language of annihilation is a common feature in ancient conquest accounts and was never meant to be taken at face value, in the next post we’ll look at the next odd feature of the text we noted in the previous post: repetitive and redundant language.

Further reading

- K. Lawson Younger Jr., Ancient Conquest Accounts: A Study in Ancient Near Eastern and Biblical History Writing (vol. 98; Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1990)

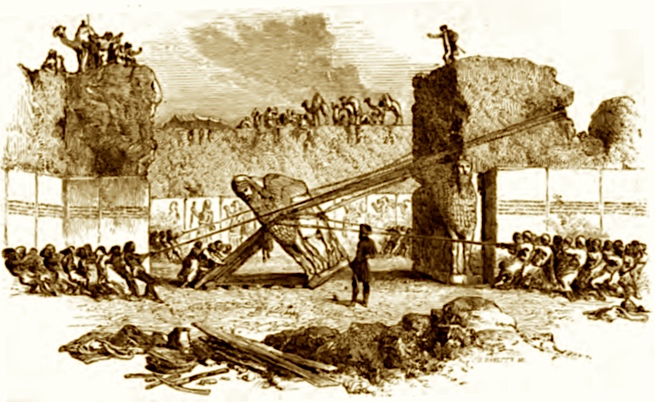

Featured image

Rameses III holds captive Nubia, Libya, and Syria – Medinet Habu relief

Footnotes

-

All scripture quotations unless otherwise noted are from the New Revised Standard Version (Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1989) ↩

-

James Bennett Pritchard, ed., The Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (3rd ed. with Supplement.; Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 378. ↩

-

William W. Hallo and K. Lawson Younger, Context of Scripture (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2000), 137–138. ↩

-

K. Lawson Younger Jr., Ancient Conquest Accounts: A Study in Ancient Near Eastern and Biblical History Writing (vol. 98; Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1990), 182–184. ↩

-

Goetze, A. Die Annalen des Muršiliš. Hethitische Texte in Umschrift, mit Übersetzung und Erläuterungen. (Vol. 6. MVAG 38. Leipzig, 1933), 78-81. ↩

-

James Bennett Pritchard, ed., The Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (3rd ed. with Supplement.; Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 262. ↩

-

H. J. Katzenstein, “Philistines: History,” ed. David Noel Freedman, The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 326. ↩

-

James Bennett Pritchard, ed., The Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (3rd ed. with Supplement.; Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 262. ↩

-

Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible 10,000-586 B.C.E. (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 1990), 300 ff. ↩