Israelite Origins: Asher & Judah

In this post we’ll take a look at how the epigraphical and archaeological evidence related to a couple of tribes can help fill in the picture about just when the Israelites emerged in Canaan.

The Tribe of Asher

Egypt’s 19th dynasty began with Rameses I, but he died after becoming Pharaoh after only one year. It was his son, Pharaoh Seti I – the father of the famous Rameses II – who really got things going. Seti is well known for his building projects; new temples sprung up all over Egypt during his reign, not to mention the restoration work he also instigated.1 His military campaigns are also noteworthy – he reinstated Egyptian dominance over Canaan, he fought the Nubians, and most well known of all, he managed to reconquer Kadesh on the Orontes.2 But, all of this had to be paid for.

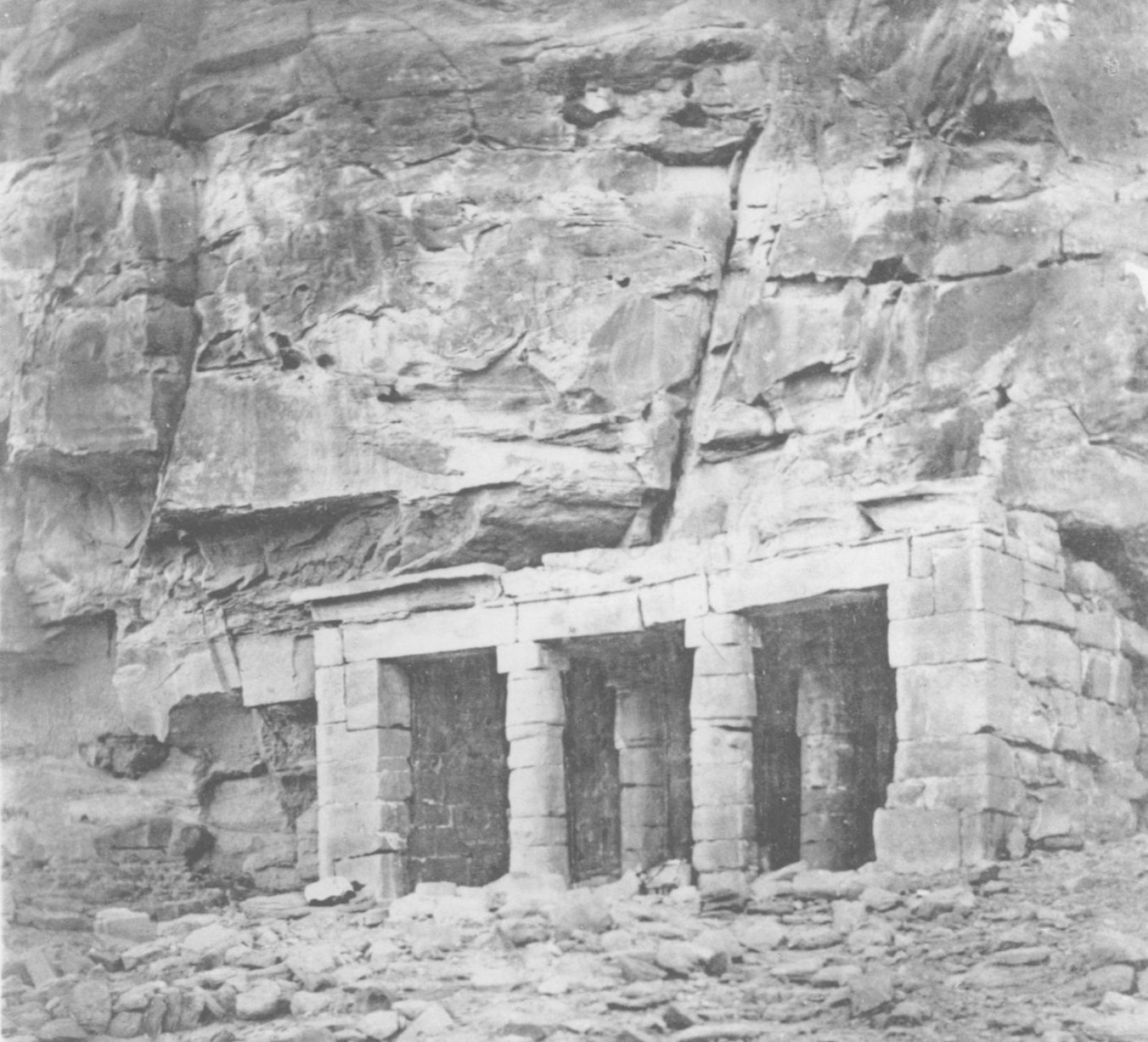

Pharaoh Seti raided Nubia for slaves he could send down newly reopened gold mines in the Sinai Peninsula and Egypt’s eastern desert. Nine years into his reign, about 37 miles along the mining road from Edfu into the eastern desert, Seti had a temple built on the spot3 where he’d previously sunk a well.4 That temple is known today as the Temple of Redesiyeh5 in Wadi Abbad.

The interior walls of the temple contain a number of texts, but for the purposes of this post we’re interested in the topographical lists carved alongside the texts – specifically the one on the western wall beneath depictions of some Asiatics.6 Here’s the pertinent bit of the sequence7:

- q-d-š

- i-ś-r

- m-k-t

Those are translated as follows8:

- Kadesh

- Asher

- Megiddo

Kadesh is “Kadesh on the Orontes” – we know where that is. Megiddo’s location is well known. But what’s “Asher”?

Wir müßten uns also geradezu Mühe geben, um die Gleichheit des von den Ägyptern erwähnten Landes אָשֵׁר und des israelitischen Stammes zu verkennen.9

And for those like me who spent their time in high school German lessons making jokes about Nazis and “not mentioning the war” instead of learning the language, here’s a translation:

We’d have to go to great lengths to fail to recognise the identity between the country mentioned by the Egyptians אָשֵׁר and the Israelite tribe.10

Müller’s claim is that the “Asher” mentioned in Pharaoh Seti I’s topographical list refers to the Israelite tribe of Asher.11

The tribal allotment of Asher is described in Joshua 19:24–31. It’s described as going,

Jos 19:28–29 …as far as Great Sidon; then the boundary turns to Ramah, reaching to the fortified city of Tyre…

That really is very far north; Asher’s tribal allotment included western Galilee but also went deep into Phoenician territory. Here’s the territory marked out on the previous map:

When it’s placed on a map, it’s clear enough why Müller’s statement is so emphatic; the Kadesh → Asher → Megiddo sequence found on Seti I’s topographical list really does correspond with the known locations of those two major towns and Asher’s tribal allotment.

There’s one glaring problem here: this topographical list dates from Pharaoh Seti I’s 9th regnal year which is around 1285 BCE. That’s long before the estimated date of around 1220 BCE for the arrival of the Israelites in Canaan demanded by a Late Date Exodus. Basically, if the Asher of Seti’s topographical list in the Temple of Redesiyeh is the same Asher that we read of as being on the Exodus in Numbers 1:40–41, then the Late Date Exodus just doesn’t stack up.12

Scholars who subscribe to a Late Date Exodus who are aware of this difficulty try to squirm out of its implications. In Kitchen’s entry for “Asher” in the New Bible Dictionary for example he mentions that “Asher” has been found to be a (female!) personal name in 1750 BCE, and that…

This particular philological discovery rules out the commonly adduced equation of biblical Asher with the ’isr in Egyptian texts of the 13th century BC as a Palestinian place-name… This eliminates the consequent suggestion that the Egyptian ’isr of 1300 BC (Sethos I) indicated an ‘Asher’-settlement in Palestine prior to the Israelite invasion later in the 13th century BC.13

This is just plain silly. Just because “Asher” was a (female!) personal name back in the time Jacob was supposed to be around doesn’t mean that the “Asher” of Seti I’s topographical list is not a reference to the area belonging to the tribe of Asher/the tribe of Asher itself.

So, though I’m not 100% sold on the correspondence between the Asher of the topographical list and the Israelite tribe, it’s hard to disagree with Müller – Kitchen has gone to great lengths to avoid the correspondence; his logic makes no sense. Most sensible bible dictionaries go along with the above evidence and reasoning. E.g. the Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary:

The association of the name Asher with the W portion of Galilee tends to be supported by Egyptian texts. The name appears with the determinative for foreign land as early as the reign of Pharaoh Seti I… The occurrence of Asher in the list of Seti I provides the clearest indication for the name’s connection with W Galilee. It appears in a geographical sequence between Kadish, probably representing the Syrian city-state of Kadesh on the Orontes River with its surrounding domain, and Megiddo, the city-state that controlled the NW portion of the Megiddo Plain-Jezreel Valley corridor. Asher seems to represent the hinterland of Phoenicia at the time of Seti I, the W Galilean hills N of Megiddo, as far as Lebanon.14

Before 1285 BCE, before any Late Date Exodus, Asher, it seems, existed as a recognisable people/place in the same area as allotted to the tribe of the same name in the book of Joshua.

I can almost hear the Early Date Exodus people chuckling smugly to themselves… Let’s move on before they feel too triumphant.

The Tribe of Judah

At the end of the wilderness wanderings a second census of the nation of Israel was taken. For Judah it’s reported that,

Nu 26:22 …the number of those enrolled [in the army] was seventy-six thousand five hundred. It’s not unreasonable to extrapolate from 76,500 warriors to a population, including women, children, and the elderly of around 200,000.

The tribal allotment for Judah is given in great detail in Joshua 15:1–12, and its towns (“with their villages”) are listed in Joshua 15:20–63. Here’s a table that summarises the information:

| Area | Count | Total |

|---|---|---|

| Extreme south (Jos 15:21–32) | 29 | 29 |

| Lowland (Jos 15:33–47) | 14 + 16 + 9 + 1 + 2 | 39 |

| Hill country (Jos 15:48–60) | 11 + 10 + 6 + 2 | 29 |

| Wilderness (Jos 15:61–62) | 6 | 6 |

| All | 103 |

In total Joshua 15 lists 103 towns for Judah.

It’s recorded that the native Canaanite population of these towns was annihilated by Joshua and the Israelite army:

Jos 10:40 So Joshua defeated the whole land, the hill country and the Negeb and the lowland and the slopes, and all their kings; he left no one remaining, but utterly destroyed all that breathed…

The end result being that the Israelite could settle, around 2,000 to a town and its villages.

Yes, this is a simplistic picture, but it’s not a straw man. It’s how many Christians deal with the text (some insisting I read it this way).

So, what does the archaeological evidence tell us about Judah’s role in the emergence of the Israelites? Well, unlike Asher where a tribe exists when it shouldn’t, Judah doesn’t exist when it should.

In a previous post we looked at the Israelite Settlement Pattern and noted that by the end of the Late Bronze Age Canaan had suffered a population collapse leaving the hill country almost empty. Over the next two hundred years the same area saw a population explosion, this population being the ancestors of people we can be certain are “biblical” Israelites.

However, this population explosion was not evenly distributed over the hill country. Mazar is careful in his summary:

Intensive archaeological surface surveys revealed an entirely new settlement pattern in Iron Age I. Hundreds of new small sites were inhabited in the mountainous areas of the Upper and Lower Galilee, in the hills of Samaria and Ephraim, in Benjamin, in the northern Negev, and in parts of central and northern Transjordan.15

The one area that is notable by its absence is Judah.

How does Mazar summarise the evidence of the Israelite Settlement Pattern in the area of the tribal allotment of Judah?

The phenomenon of many small, one-period sites attributable to the Israelite settlement is almost completely nonexistent in the Hebron Hills south of Bethlehem and in the Shephelah of Judah. Here, perhaps the Israelites contented with a smaller number of sites, which later, in the period of the Monarchy, developed into towns.16

“Almost completely non-existent”. Huh.

Stager’s figures that we’ve previously seen in the post about the Israelite Settlement Pattern show that in the Late Bronze age there were zero sites in Judah – put quite starkly by Mazar, “The Late Bronze Age in the Judaean Highland is a void”17, and described by Offer as, “an almost complete gap in occupation”18. In Iron I – the period of the Conquest of Canaan and the period of the Judges – the number of sites increase, but only to a total of eighteen. A total population estimate for these 18 sites is a mere 4,000 people.19

Far from being the largest of the Israelite tribes as they’re described in Numbers 26, a population of 4,000 isn’t much more than a small village. All the archaeological evidence suggests that while the rest of the Canaanite highlands were being settled, Judah remained practically empty. It’s not until the beginning of Iron IIA (~1000 BCE, the time of David) that Judah’s population starts to climb.20

So, far from being the most successful tribe at taking their inheritance as they’re depicted in Judges 1:1-20, where we’d expect to see the most significant and obvious settlement we barely see any at all. It’s as if the tribe of Judah didn’t even turn up to take possession of its tribal allotment.

What are we to make of this?

On the one hand we have a the tribe of Asher in its allotted territory before they’d even left Egypt, and on the other we appear to have lost our largest and most significant tribe!?

Earlier on, when we’d only covered Asher being in situ before 1285 BCE, the Early-Date-Exodus people were looking very pleased with themselves. Now, with people only turning up in the area of the tribal allotment of Judah at around the time of David, both Early and Late Date Exodus people are starting to look a little silly.

The fact of the matter is this: though in the main the Israelite Settlement happened across the Canaanite highlands in the 12th and 11th centuries, it didn’t happen uniformly across the whole area. Some of the people groups who went on to make up the nation of Israel appeared in the various tribal allotments at different times. This doesn’t match simplistic Sunday School stories, it doesn’t match an Early Date Exodus, and it doesn’t match a Late Date Exodus.

In the next post we’ll take a look at what one of the oldest texts in scripture can tell us about the Tribes of Israel.

Featured image

Looking south down Israel’s Mediterranean coastline from Rosh HaNikra

Footnotes

-

Jacobus Van Dijk, “The Amarna Period and Later New Kingdom,” in The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, ed. Ian Shaw (Oxford University Press, 2003), 286-288. ↩

-

Donald B. Redford, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times (Princeton University Press, 1992), 180-181. ↩

-

Location: https://goo.gl/maps/hCnrbyqDPsCNoZp78 ↩

-

Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume II: The New Kingdom (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973–), 52. ↩

-

“The temple of Sety 1st which stands in the Wady Abad, some thirty-five miles east of Edfu, is generally known as the temple of Redesiyeh, owing to the fact that one of the early explorers set out to visit the building from the village of Redesiyeh… Redesiyeh is a place of no importance, and has no connection with the building other than that of having been by chance the starting-point of a journey once made to it long ago.” Arthur Weigall, A Guide To The Antiquities Of Upper Egypt: From Abydos To The Sudan Frontier (1910), 351. ↩

-

Simons, Handbook for the Study of Egyptian Topographical Lists Relating to Western Asia (Leiden: Brill, 1937), 61-63. ↩

-

There is no question of what the inscription says. As Breasted explains, “The god here leads only six countries, of which Shinar, Shasu, Kadesh, Ashur, and Megiddo are certain.” James Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, Vol. 3, 79, note C. ↩

-

Ibid., 147. ↩

-

Muller, Asien und Europa nach Altägyptischen Denkmälern (Leipzig, 1893), 237. ↩

-

Improvements on this translation are gladly received :) ↩

-

Seti’s topographical list is not the only place where “Asher” appears in a list of western Asiatic toponyms. It also features in a list in the Temple of Rameses II at Abydos. See Simons, Handbook for the Study of Egyptian Topographical Lists Relating to Western Asia (Leiden: Brill, 1937), 75-76, 162. ↩

-

…unless Asher was living in their tribal allotment in northern Canaan before they’d even left Egypt, which of course, is a nonsense suggestion. ↩

-

K. A. Kitchen, “Asher,” ed. D. R. W. Wood et al., New Bible Dictionary (Leicester, England; Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1996), 92. ↩

-

Diana V. Edelman, “Asher (Person),” ed. David Noel Freedman, The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 482. ↩

-

Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible 10,000-586 B.C.E. (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 1990), 334. ↩

-

Ibid., 336. ↩

-

Amihai Mazar, Studies in the Archaeology of the Iron Age in Israel and Jordan, vol. 331, Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series (Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001), 26. ↩

-

Avi Offer, “Hill Country of Judah,” in From Nomadism to Monarchy, eds., Israel Finkelstein & Nadav Na’aman (Yad Izhak Ben Zvi, Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1994), 100. ↩

-

Avi Offer, “Judea,” in The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, Vol. 3, ed. Ephraim Stern (Israel Exploration Society & Carta, 1993), 816. ↩

-

“In general, Iron I-IIA constitutes the most significant breakthrough in the settlement history of the Judean Hills.” Avi Offer, “Hill Country of Judah,” in From Nomadism to Monarchy, eds., Israel Finkelstein & Nadav Na’aman (Yad Izhak Ben Zvi, Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1994), 103-4. ↩