Israelite Origins: Egyptian domination of Canaan

Nu 13:28–29 “…the people who live in the land are strong, and the towns are fortified and very large; and besides, we saw the descendants of Anak there. The Amalekites live in the land of the Negeb; the Hittites, the Jebusites, and the Amorites live in the hill country; and the Canaanites live by the sea, and along the Jordan.”

Such was the report of the 12 tribal representatives sent by Moses to spy out the promised land. Based on this passage we may imagine that Canaan was a land of strong, well defended city states.

40 years after the spies’ report, on the plain of Moab just before his death, Moses reiterated the same sentiments:

Dt 9:1–2 Hear, O Israel! You are about to cross the Jordan today, to go in and dispossess nations larger and mightier than you, great cities, fortified to the heavens, a strong and tall people, the offspring of the Anakim, whom you know.

This second passage helps to fill out the picture – the Israelites faced a number of Canaanite tribes, namely, the Amalekites, the Hittites, the Jebusites, the Amorites, and the Canaanites; and we know where they lived, namely, the Negev desert in the south, the hill country, the Mediterranean coast, and in the Jordan valley. That’s pretty comprehensive – the land from north to south, from east to west, was filled with Canaanites in great cities with massive walls.

From the point of view of scripture alone, that’s the situation we’d expect to be the case in Canaan around 40 years before the Israelites began the conquest of Canaan. However, the archaeological and epigraphical data would disagree…

On becoming the sole ruler of Egypt in around 1458 BCE1 after 21 years co-regency with his aunt Hatshepsut, Thutmose2 III lost little time making a name for himself that would echo down the halls of time.

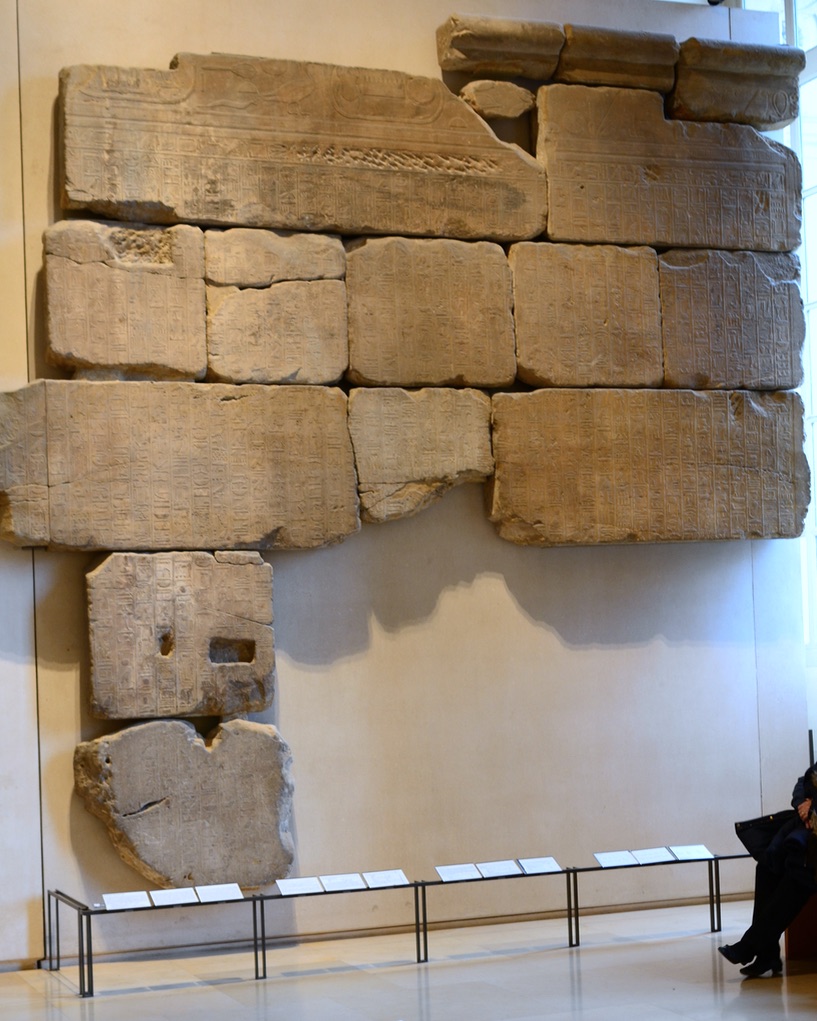

Thutmose III began the first and most decisive of the great conqueror’s campaigns3 in the region of Canaan and Syria establishing Egyptian dominance over the region. The first of these campaigns was recorded in detailed relief in Thutmose’s annals on the walls in the temple at Karnak, now in the Louvre Museum in Paris. Usefully for us today the annals are an example of Egyptian royal records at their most realistic and least rhetorical4 so their historicity needn’t be dismissed out of hand.

Reading through them we find that Thutmose III travelled through Gaza, Yehem, and on to Megiddo where he fought against a coalition of Canaanites and other peoples from the Levant that were stationed in that city.

The Annal’s description of the way it took place makes for fun reading:

His majesty set out on a chariot of fine gold, decked in his shining armor like strong-armed Horus, lord of action, like Mont of Thebes, his father Amun strengthening his arm… Then his majesty overwhelmed them at the head of his army. When they saw his majesty overwhelming them, they fled headlong [ to ] Megiddo with faces of fear, abandoning their horses, their chariots of gold and silver, so as to be hoisted up into the town by pulling at their garments.5

So far all was going to plan. The problem for Thutmose III was that instead of finishing the job, his army got distracted by loot:

Now if his majesty’s troops had not set their hearts to plundering the possessions of the enemies, they would have [ captured ] Megiddo at this moment…6

Instead, they had to put the city under siege and wait for those holed up to come “on their bellies to kiss the ground to the might of his majesty, and to beg breath for their nostrils…“7 as the Annals record.

After seven months8 the siege broke. Thutmose III received a whole load of booty from the city, and, most importantly, “replaced the defeated local chiefs”9, appointing petty kings in a divide-and-rule strategy.

So began Egypt’s domination of Canaan. For the next 250 or so years Egypt ruled Canaan with an iron fist:

Egypt now ruled over a hegemonic empire in western Asia. City-states from Canaan to southern Syria acknowledged the pharaoh as their suzerain, paid tribute, and sent their children to Egypt when requested to do so—the girls as member of the royal harim, the boys as hostages who would be returned to their homes properly trained in loyalty to their overlord when their turn to rule came.10

The Pharaohs that succeeded Thutmose III from both the rest of the 18thand 19th dynasty all kept an interest in Canaan with only infrequent rebellions to squash.

The Egyptian presence in Canaan was significant. For example it was at Beth-Shean that the largest concentration of Egyptian monuments outside of Egypt was uncovered.11 They set up administrative centres in Aphek, Gaza, and Jaffa.12

But, what stands out most in the archaeological record from the time period of Egyptian domination isn’t so much what was there as wasn’t– from the time of Thutmose III until the end of Egyptian rule, almost all towns in Canaan had no city wall.13 Excluding Hazor, Megiddo, and (possibly) Gezer – the very largest Canaanite cities – the only towns with walls constructed in the Late Bronze age are Ashdod, Tel Abu Hawam, and Tel Beit Misrim.14 The rest stood vulnerable and unprotected – just how Pharaoh wanted them.

This was a highly unusual state of affairs in the ancient Near East and is a demonstration of just how tight Egyptian control was:

How can we explain the lack of fortifications at cities which in the preceding period were heavily defended? The most plausible assumption is that Egyptian policy in Canaan outlawed the building of fortifications by Canaanite rulers.15

In fact, Egyptian rule was so tight that with Egypt firmly in charge of security for the entire province, there was no need of massive defensive walls.16

The subservience of the Canaanite petty kings shown as a result of theirvulnerable position is shown in letters they wrote to Pharaoh, many of which have been discovered at Amarna. Here’s a selection of some of the ways they opened their letters:

EA 286 (from the ruler of Jerusalem): Say [t]o the king, my lord: Message of ʿAbdi-Ḫeba, your servant. I fall at the feet of my lord, the king, 7 times and 7 times.17

EA 254 (from the ruler of Shechem): To the king, my lord and my Sun: Thus Lab’ayu, your servant and the dirt on which you tread. I fall at the feet of the king, my lord and my Sun, 7 times and 7 times. I have obeyed the orders that the king wrote to me. Who am I that the king should lose his land on account of me? The fact is that I am a loyal servant of the king!18

EA 228 (from the ruler of Hazor): Say [t]o the king, my lord: Message of ʿAbdi-Tirši, the ruler of Ḫaṣuru, your servant. I fall at the feet of the king, my lord, 7 times and 7 times «at the feet of the king, my lord».19

A ‘ruler’ who feels he has to open a letter to Pharaoh in such a grovelling manner is quite clearly not in charge. Far from it. Here’s one particularly embarrassing example:

EA 277 (from the ruler of Qiltu): [To the king, my lord, my god, my Sun: Message of …], yo[ur ser]vant, [the dirt at] your [fee]t. [I fa]ll [a]t the fe[et of the king, my lord], my god, [my Sun], 7 times and 7 t[imes]. The order that the king, my lord, my god, my Sun, sent to me, I am indeed carrying out for the king, my lord.20

Yes, that is the whole letter.

The petty Canaanite kings report squabbles between themselves to Pharaoh, asking him to step in like little children do their parents:

EA 246 (from the ruler of Megiddo): The two sons of Lab’ayu have indeed gi[v]en their money to the ʿApiru and to the Su[teans in ord]er to w[age war again]st me.[May] the king [take cognizance] of [his servant].21

It really is pitiable stuff.

Another aspect of the Egyptian domination of Canaan that ought to be pointed out is the policy of depopulation placed on the natives. Here’s Redford’s summary:

Thutmose III carried off in excess of 7,300, while his son Amenophis III uprooted by his own account 89,600. Thutmose IV implies that he carried off the inhabitants of Canaanite Gezer to Thebes, while his son Amenophis III speaks of his Theban mortuary temple as “filled with male and female slaves, children of the chiefs of all the foreign lands of the captivity of His majesty – their number is unknown – surrounded by the settlements of Syria.”22

We’re going to come back to the topic of Late Bronze age deportation in a future post and get into the detail there, but for now we just need to understand that depopulation happened, and it left Canaan all the more weakened and all the more in the shadow of Egypt.

In summary then, Canaan became essentially a province of a newly formed Egyptian empire, ruled over by Pharaoh who through various policies kept the petty kings he’d installed in a vulnerable position. Under Egyptian rule the grand and wealthy city states of Canaan became impoverished and defenceless.

So, what does the Egyptian domination of Canaan have to do with Israelite origins? Well, a fair bit.

Firstly, if the Exodus and conquest of Canaan occurred as read in 1446 and 1406 BCE as the Early Date Exodus timeframe demands (i.e. you take the Masoretic Text of 1 Kings 6:1 at face value ignoring everything else the Bible tells us about the date of the Exodus), it’s curious that the book of Joshua doesn’t mention an Egyptian presence in Canaan. It describes all the battles the Israelites fought as being against Canaanite coalitions – here they are:

Jos 10:3–4 “So King Adoni-zedek of Jerusalem sent a message to King Hoham of Hebron, to King Piram of Jarmuth, to King Japhia of Lachish, and to King Debir of Eglon, saying, “Come up and help me, and let us attack Gibeon; for it has made peace with Joshua and with the Israelites.”

Jos 11:1–4 “When King Jabin of Hazor heard of this, he sent to King Jobab of Madon, to the king of Shimron, to the king of Achshaph, and to the kings who were in the northern hill country, and in the Arabah south of Chinneroth, and in the lowland, and in Naphoth-dor on the west, to the Canaanites in the east and the west, the Amorites, the Hittites, the Perizzites, and the Jebusites in the hill country, and the Hivites under Hermon in the land of Mizpah. They came out, with all their troops, a great army, in number like the sand on the seashore, with very many horses and chariots.”

There’s no mention of Egyptian domination, Egyptian outposts, or Egyptian armies. There are just independent Canaanite city states defended by massive Canaanite armies – just as a flat, face value reading of the spies’ report recorded in Numbers would have us believe. And that’s rather odd given that almost all towns in Canaan were unwalled, underpopulated, and in thrall to the Egyptians. If the book of Joshua was situated in the Late Bronze age, as the Early Date Exodus and conquest demand, we’d read of battles against Egyptians, not Canaanites.

Quite simply, the book of Joshua doesn’t reflect the reality on the ground in Canaan in the early 14th century BCE. If you want to persist with holding to the Early Date Exodus and conquest you need to come up with an explanation as to why the Egyptian domination of Canaan gets not a single mention in the book of Joshua.2324

If the Early date is out, what about the Late Date Exodus and conquest? Does the book of Joshua describe what was going on in Canaan at the end of the 13th century as that timeframe demands? As Finkelstein explains, in the thirteenth century BCE, the grip of Egypt on Canaan was stronger than ever.25 So, for all the same reasons as it doesn’t work for the Early Date, the Late Date conquest theory doesn’t fit with the archaeological and epigraphical evidence either.

In conclusion: the biblical record, and particularly the book of Joshua, is found, at least on a flat and context-free reading, to describe a situation that doesn’t match the basic facts. It describes powerful coalitions of powerful Canaanite city states, yet in reality most towns were weak, and defenceless. It describes massive armies, and yet the Egyptians had put in place a policy of depopulation. Finally, nowhere in the biblical record is it mentioned that Canaan was under absolute Egyptian domination.

Yet, in around 1208 BCE, the epigraphical evidence of the Merneptah Stele shows us that there was a people group, almost certainly locatedin the hill country, that the Egyptians called “Israel”.

In the next post we’ll get into our last bit of background before we finally start talking about Israelite Origins: the topic of the Late Bronze Age Collapse.

Further reading

- Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman, “A Different Kind of Canaan”, in The Bible Unearthed (Free Press, 2001), 76–79.

- Amihai Mazar, “In the Shadow of Egyptian Domination: The Late Bronze Age,” in Archaeology of the Land of the Bible 10,000-586 B.C.E. (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 1990), 232–290.

- William J. Murnane and Edmund S. Meltzer, Texts from the Amarna Period in Egypt (vol. 5; Writings from the ancient world; Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1995)

- Donald B. Redford, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times (Princeton University Press, 1992), 156-213.

- Ian Shaw, “Thutmose III in the Levant,” in The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt (Oxford University Press, 2000), 237-241.

Featured image

The House of the Egyptian Governor, Beth Shean. In the background you can see over the Jordan valley to northern Gilead.

Footnotes

-

Dates and time periods relating to Egyptian chronology are from Ian Shaw, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt (Oxford University Press, 2000), 480-490. ↩

-

AKA “Tuthmosis”, AKA “Thutmosis”, AKA various other similar spellings. ↩

-

Donald B. Redford, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times (Princeton University Press, 1992), 156. ↩

-

Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume II: The New Kingdom (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973–), 29. ↩

-

Ibid., 32. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid., 33. ↩

-

As explained on the Gebel Barkal Stele: “When they entered into Megiddo, my majesty shut them up for a period up to seven months, before they came out into the open, pleading to my majesty and saying: ‘Give us thy breath, our lord!’” James Bennett Pritchard, ed., The Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (3rd ed. with Supplement.; Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 238. ↩

-

Shaw, op. cit., 208. ↩

-

William J. Murnane and Edmund S. Meltzer, Texts from the Amarna Period in Egypt (vol. 5; Writings from the ancient world; Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1995), 2. ↩

-

Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible 10,000-586 B.C.E. (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 1990), 282. ↩

-

Ibid., 236 & 247. ↩

-

Ibid., 243. ↩

-

Ibid., 243. ↩

-

Ibid., 243. ↩

-

Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman, The Bible Unearthed (Free Press, 2001), 77. ↩

-

Moran, op. cit., 326. ↩

-

Ibid., 307. ↩

-

Ibid., 289. ↩

-

Ibid., 320. ↩

-

Ibid., 300. ↩

-

Redford, op. cit., 208-209. ↩

-

You’re also going to have to come up with an explanation for the fact that the book of Joshua mentions the Philistine pentapolis (Jos 13:3); something that wasn’t in place until the late 11th century BCE. We’ll get into this interesting quirk in a future post. ↩

-

Oh, and I’m afraid that chronological revisionism doesn’t count – we’re interested in reality, not wishing it away. ↩

-

Finkelstein & Silberman, op. cit., 78. ↩