Israelite Origins: The Merneptah Stele

If there’s one archaeological discovery that always comes up in discussions about early Israel it’s the Merneptah Stele. In this post we’re going to take a look at what it is, and what it tells us (and doesn’t tell us) about Israelite origins.

On Wednesday 8th of April 1896, shortly arriving back in England, Professor William Flinders Petrie gave a lecture at University College London. Having recently returned from excavations in Egypt this towering figure in Egyptology shared the details of a discovery he’d made only a couple of months before, a discovery known today as the Merneptah Stele.

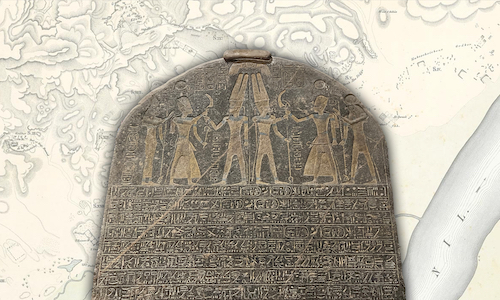

On its discovery Flinders Petrie wasn’t slow to realise the stele’s significance – on the same night he learned what the inscription on the large, black, granite slab said, he declared, “This stele will be better known in the world than anything else I have found.”1 To this day it remains one of the most significant artefacts related to the history of early Israel, and it’s certainly what Flinders Petrie is best known for – unless you’re an Australian when greater significance is placed on him being the grandson of Matthew Flinders.2

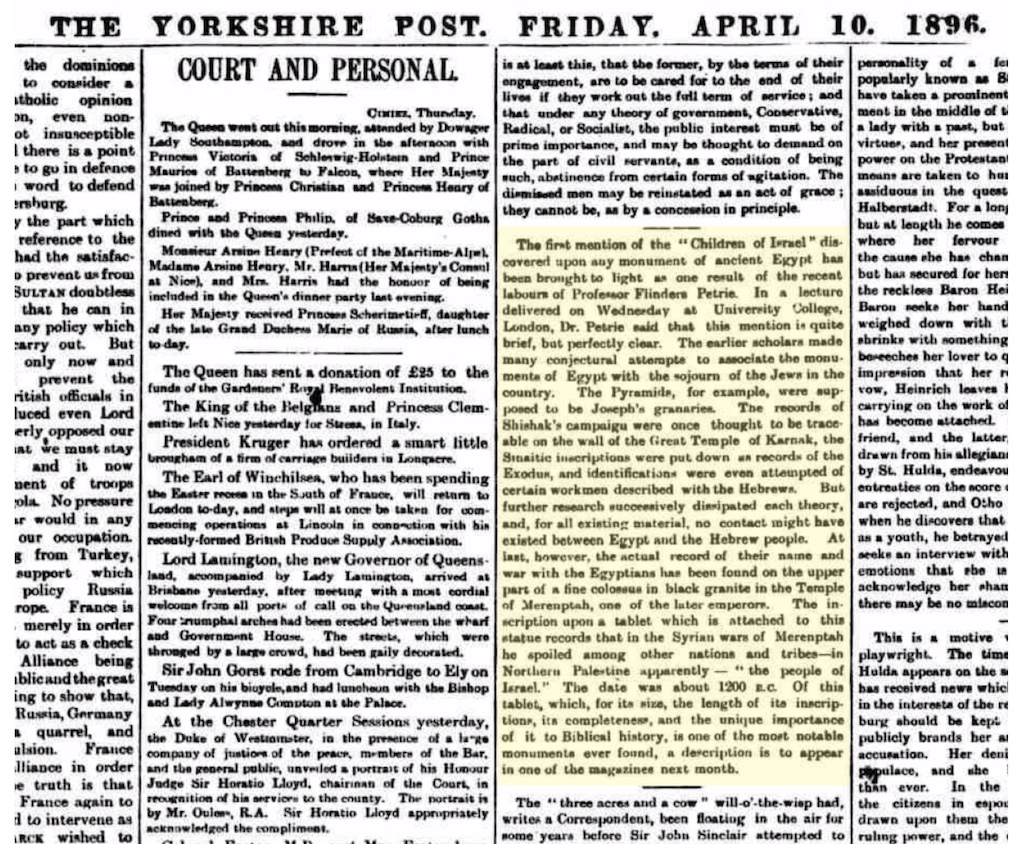

News of the stele caused a sensation. Only two days after his lecture, readers of the Yorkshire Post3 were given the highlights by the journalist who’d attended Flinders Petrie’s lecture:

The first mention of the “Children of Israel” discovered upon any monument of ancient Egypt has been brought to light as one of the results of the recent labours of Professor Flinders Petrie… this mention is quite brief, but perfectly clear.4

Discovery

A few weeks earlier Flinders Petrie had been in Egypt, excavating temples in Thebes on Luxor’s west bank over the winter of 1895-1896. One of these was the Temple of Merneptah (or “Merenptah” as he used to be referred to as) – for the sake of any who’ve toured Egypt, it’s behind (north-west of) the Colossi of Memnon.

Flinders Petrie was not impressed by what he found:

The site of Merenptah’s temple was disastrously dull; there were worn bits of soft sandstone, scraps looted from the temple of Amanhetep III, crumbling sandstone sphinxes, laid in pairs in holes to support columns.5

Though the end of his reign was peaceful enough Merneptah ruled during the beginning of the Late Bronze Age collapse and he suffered the first waves of the invasions of the Sea People. He didn’t have the time or resources to replicate his father Ramses II’s grand building projects, and coming to the end of his life,

[Merneptah] must have realized that he did not have many years left, however, for his mortuary temple on the Theban West Bank is constructed almost exclusively from blocks removed from earlier structures, particularly the nearby temples of Amenhotep III.6

Elsewhere Flinders Petrie wrote that the destruction and looting Menreptah had inflicted on his predecessor Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple was,

…as bad as anything ever done by Turk or Pope…7

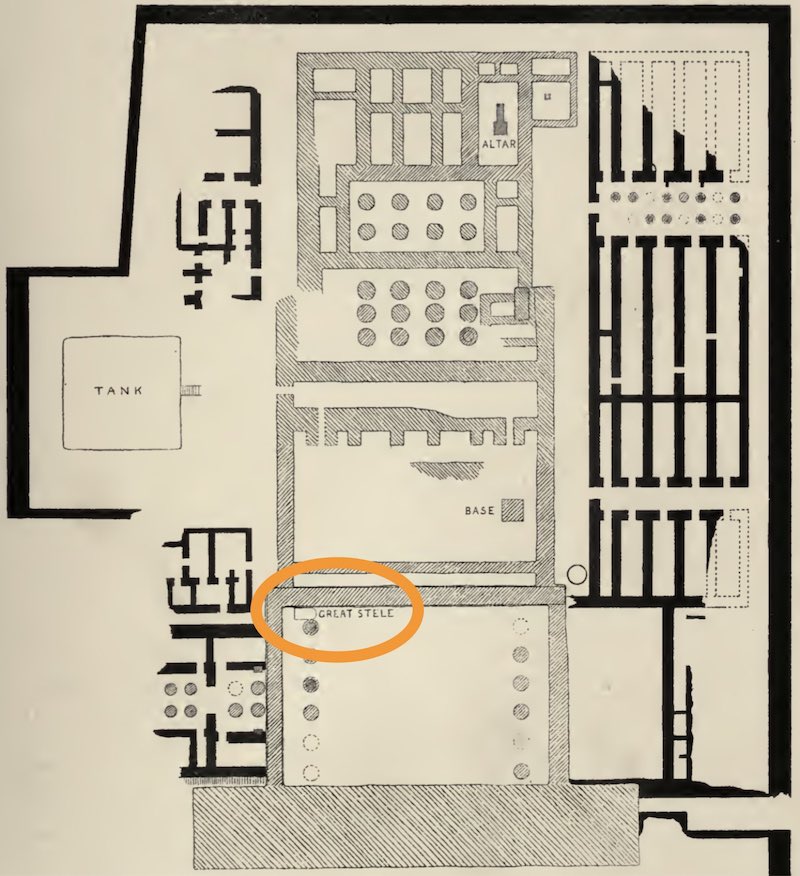

Quite the statement. As disappointed with Merneptah’s temple as Flinders Petrie was, the discovery of the Stele was the highlight of the expedition. It was found face down,

…in the S.W. corner of the first court. It had evidently stood against the south wall in the corner, and been overthrown forwards. It rested on the base of the column at its east side.8

The stele was originally Amenhotep III’s. On it he described his building projects that included his mortuary temple, the Luxor temple, and the third Pylon at Karnak.9 Many years later Merneptah took the Stele and had his own inscription written on the back of it.

Transcription and translation

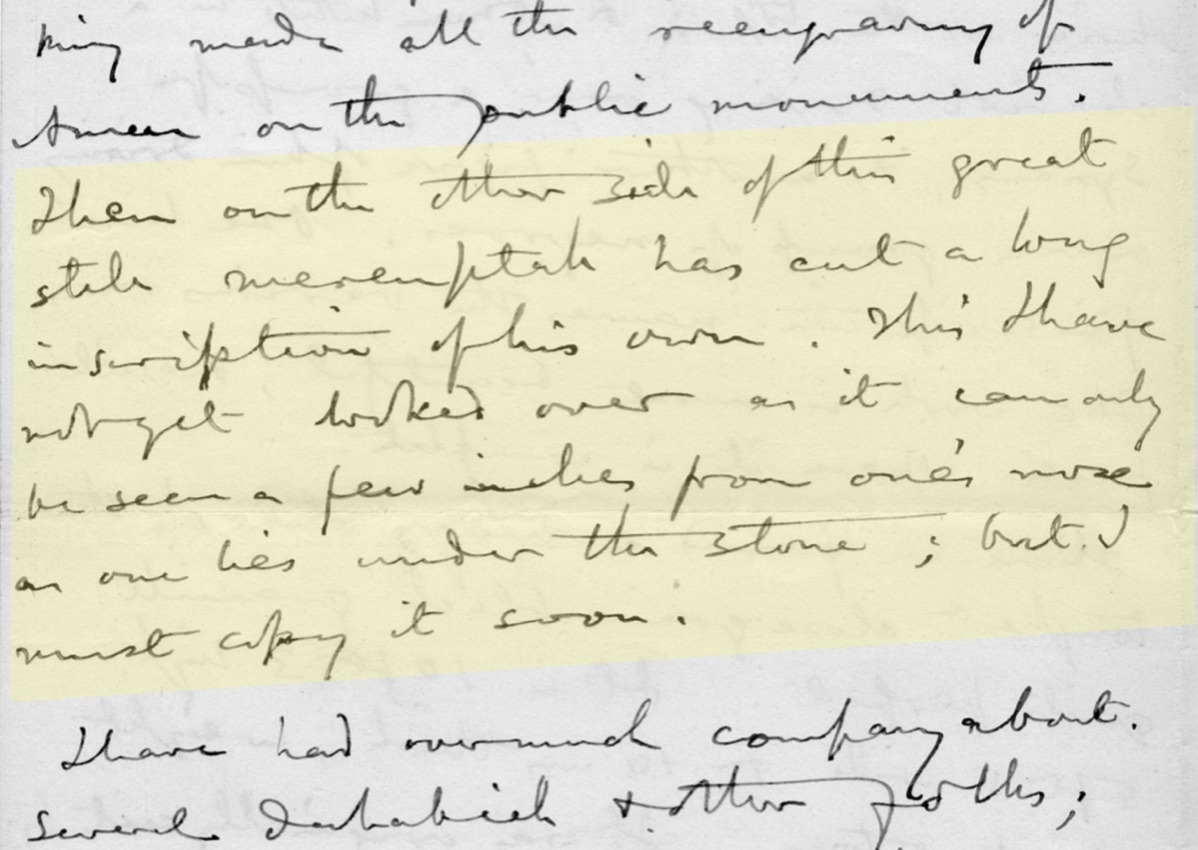

Flinders Petrie had the ground below the stele shovelled out creating a small space to crawl into. Some of Flinders Petrie’s notebooks are publicly available; here’s a transcript of what he wrote on the stele’s discovery where he mentions this small space:

…Then on the other side of this great stele Merenptah has cut a long inscription of his own. This I have not yet looked over as it can only be seen a few inches from one’s nose as one lies under the stone; but I must copy it soon.10

Dr Spiegelberg of Strasbourg University, working with Flinders Petrie on translating inscriptions,

…lay there copying for an afternoon, and came out saying, “There are names of various Syrian towns, and one which I do not know, Isirar.” “Why, that is Israel,” said I. “So it is, and won’t the reverends be pleased,” was his reply.11

And so the significance of the stele was established; the earliest mention of “Israel” outside the bible.

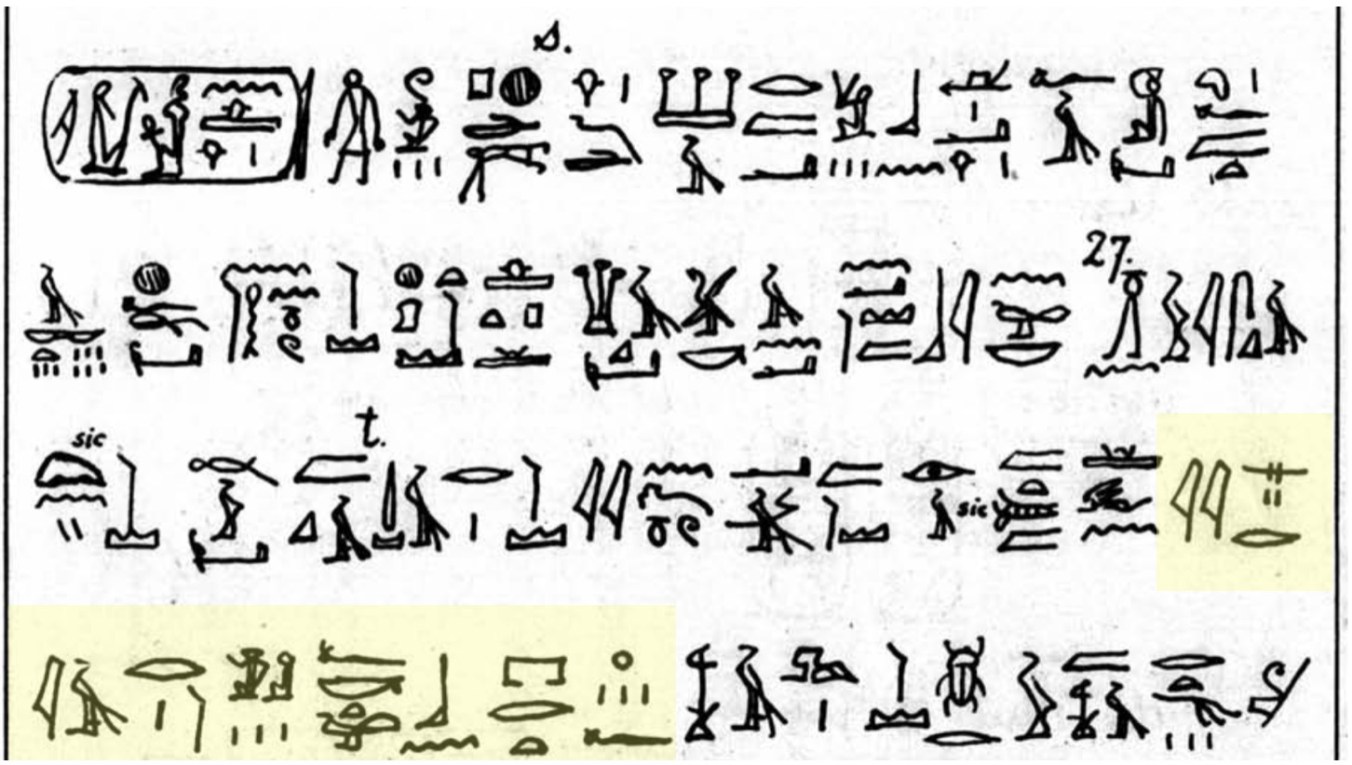

Spiegelberg wasted no time and published his transcription the same year.12 Here’s the pertinent bit, found on line 27 of the inscription:

The mention of Israel comes almost at the end of the stele in a list of places and towns Merneptah had fought. Here’s Spiegelberg’s translation:

The princes bend down, saying ‘Hail!’ Not one raises his head among the Nine Bows. Devastated is Tehenu, Kheta is quieted, Seized is the Kanaan with every evil, Led away is Askelon, Taken is Gezer, Yenoam is brought to nought, The people of Israel is laid waste,— their crops are not, Khor (Palestine) has become as a widow for Egypt, All lands together—they are in peace. Every one who roamed about Is punished by King Merenptah, gifted with life, like the sun every day.13

A more recent translation benefiting from more than 100 years of scholarship14 is as follows:

The (foreign) chieftains lie prostrate, saying “Peace.” Not one lifts his head among the Nine Bows. Libya is captured, while Hatti is pacified. Canaan is plundered, Ashkelon is carried off, and Gezer is captured. Yenoam is made into non-existence; Israel is wasted, its seed is not; and Hurru is become a widow because of Egypt. All lands united themselves in peace. Those who went about are subdued by the king of Upper and Lower Egypt … Merneptah.15

So, who or where is “Israel”?

Merneptah’s Israel – a people or a place?

Since the discovery of the Merneptah Stele, a considerable amount of noise has been made about the fact that its mention of “Israel”, in contrast to Canaan, Ashkelon, Gezer, Yenoam, and Hurru, is given the people determinative instead of the place determinative. In other words, whoever wrote the inscription thought of “Israel” as a people rather than a place. Petrie explained this in an 1896 article as follows:

That the name here is that of the people Israel, and not of the city Jezreel, is shown by the writing of it with s and not z, and by its being expressly a “people” unlike the other names here, which are those of “places.”16

This reasoning, along with its implications for what it means for understanding the relevant biblical narratives, remains the same today. For example, here’s an excerpt from Hoffmeier’s entry for the Merneptah Stele in Context of Scripture:

It has long been noted that the writing of Israel uses the determinative (semantic indicator) for an ethnic group, and not for a geographic region or city. This scenario is in complete agreement with the picture portrayed in the books of Joshua and Judges, viz. the Israelites had no clearly defined political capital city, but were distributed over a region.17

The same reasoning about the determinative can be found across the spectrum18, from very conservative19, conservative20, middle-of-the-road, 212223and even minimalist works24.

The thing is, it’s probably not that clear cut. As Miller points out, the people determinative is used on this same stele for places, specifically,

A thorough examination of Egyptian scribal practice, however, shows the use of the determinative to be almost completely arbitrary… Within the Merneptah Stele itself, in lines 4–5 the Meshwesh, who are definitely a people, have the city-state determinative; in line 5 and line 10 the Libyan people (rbw) have the city-state determinative; and in lines 11 and 21 Libya (Tjehenu [thnw]) has both the people determinative and the city-state determinative. The determinatives should not be overread for “what they say about Israel.”25

If that is the case, and plenty seem to agree26, then insisting that the Israel of the Merneptah Stele refers to a people group rather than a city/location is probably going too far.

Locating Merneptah’s Israel

What’s more insightful is William Dever’s argumentation working out where Israel, in the mind of the scribe, was located.27 Let’s go through that now.

As we’ve already mentioned, “Israel” appears in the final section of the Stele, a section which records Merneptah’s campaign in Canaan – fictional or otherwise.28 That helps pin down the area in which Israel, people or place, must have been located – somewhere in the southern Levant. So, where was it?

Well, according to Dever here’s where Israel couldn’t have been:

- The coast and lowlands were run by Egyptian vassal city states, like Ashkelon and Gezer.

- Galilee, being the northern part of Canaan, was under Egyptian control

- The southern Negev, according to other New Kingdom Egyptian texts was never conquered, nor did it need to be.

That leaves the central hill country. And Dever’s not alone in this. Miller makes the same point:

The Merneptah Stele is direct positive evidence that the term “Israel” was used for some entity in the highlands of Palestine in the parlance of Late Bronze IIb sources.29

However, Noll makes the case that Israel were/was not in the central hill country:

Israel… apparently, lived in the vicinity of Ashkelon, Gezer and Yanoam, thus, perhaps the Cisjordan Highlands or the Jezreel Valley. The latter is more likely since, from archaeological surveys, it would seem that very few people were living in the hills of Canaan. It is not impossible that Merneptah did battle with the few people who were living in the hills at that time. It would have been a short and one-sided battle! I suspect, however, that Israel was part of the lowland population.30

However, Dever’s response to this sort of argument is pretty strong:

Is it merely a coincidence that most of the 13th–12th century B.C. villages recently brought to light by archaeology are located precisely [in the central hill country]?31

If the people living in the villages that make up the Israelite Settlement pattern we looked at in the previous post were the ancestors of people who lived 200 years later that we’re all happy to call “Israel”, it kinda makes sense to associate Merneptah’s “Israel” with either the central hill country (or a part of it), or with a group of people living in it. Miller explains this better than I can:

…it makes no difference what the Iron I highlanders called themselves: they were the direct antecedents of Iron II Israel and, thus, “Proto-Israel.” There is direct continuity from the Iron I highlands to Iron II Israel and Judah in pottery, settlements, architecture, burial customs, and metals… So whatever the Iron I highlanders called themselves, by their continuity with Iron II they were nevertheless “those elements that were not yet Israel, but which went into or led up to the creation of Israel” (Thompson 1987:33). Yet since the Merneptah Stele records that the name of this community, or at least part of it, was Israel, once archaeology has established the continuity to Iron II, there is no reason to retain the prefix “Proto-.”32

Anyway, regardless of whether Merneptah’s “Israel” is a place or a people, and regardless of whether it was/they were located in the central hill country or the Jezreel Valley, what actually matters is this:

According to Merneptah, defeating Israel was something worth writing home about.

Pretty much any scholar writing about the stele makes this point. Here are a few examples:

Israel was no less significant than Ashkelon and Gezer, two of the more important city-states in Palestine at the time.33

This Israel was well enough established by that time among the other peoples of Canaan to have been perceived by Egyptian intelligence as a possible challenge to Egyptian hegemony.34

Israel functioned as an agriculturally-based/sedentary socioethnic entity in the late 13th century B.C., one that is significant enough to be included in the military campaign against political powers in Canaan.35

I could go on, but I won’t. You’re not paying me for this.

The point is clear: if Merneptah felt that defeating Israel was as big a deal as defeating the mighty cities of Ashkelon and Gezer, then “Israel” wasn’t an insignificant entity. It must have been a relatively big deal, at least in the context of Late Bronze Age Canaan.

A fly in the ointment

There’s one problem with all this: the Israelite Settlement Pattern we went through in the previous post didn’t begin until maybe 50-70 years after Merneptah’s mention of Israel. That makes it hard to demonstrate a one-to-one correspondence between Merneptah’s Israel and those who settled the Canaanite highlands.

In our next post we’ll take a look at what one particular Israelite tribe can tell us about Israelite Origins…

Featured image

A very grainy photo of the Merneptah Stele from Petrie’s Six Temples at Thebes entitled, “Black Granite Stele of Merenptah PL. XIII.”

Footnotes

-

William Flinders Petrie, Seventy Years in Archaeology (New York, 1932), 172. Available here. ↩

-

Sidney Smith, Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society, Vol. 5, No. 14 (November 1945), 3. Also, in unrelated but relatively recent Matthew Flinders news… ↩

-

Let the record show that back when I was 13 years old I delivered the Yorkshire Post on my paper round – a short career that came to a sudden and abrupt end after sleeping in and missing my round. Twice. In a row. ↩

-

Yorkshire Post, April 10, 1896, page 4, column 5. Available here. ↩

-

Flinders Petrie, Seventy Years in Archaeology (New York, 1932), 171. Available here. ↩

-

Ian Shaw, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt (Oxford University Press, 2003), 295. ↩

-

Flinders Petrie, “Egypt and Israel,” The Contemporary Review, May 1896, 619. Available here. ↩

-

Flinders Petrie, Six Temples at Thebes, 1896 (London, 1897), 13. Available here. ↩

-

Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume II: The New Kingdom (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973–), 43–47. ↩

-

Petrie MSS 1.13 – Petrie Journal 1895 to 1896 (Thebes). Available here. ↩

-

Flinders Petrie, Seventy Years in Archaeology (New York, 1932), 172. ↩

-

Wilhelm Spiegelberg, “Der Siegeshymnus des Merneptah auf der Flinders Petrie-Stele,” Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde, Volume 34, Issue 1 (1896): 1-25. Available here. ↩

-

Flinders Petrie, Six Temples at Thebes, 1896 (London, 1897), 28. ↩

-

There has been a tremendous amount of scholarship on what the inscription says and how it should be translated. For a summary of many of the issues and a sensible conclusion see Michael G. Hasel, “Israel in the Merneptah Stela,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (November), no. 296 (1994): 45-61. ↩

-

William W. Hallo and K. Lawson Younger, Context of Scripture (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2000), 41. ↩

-

Flinders Petrie, “Egypt and Israel,” The Contemporary Review, May 1896, 624. Available here. ↩

-

William W. Hallo and K. Lawson Younger, Context of Scripture (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2000), 41. ↩

-

I guess the following labels and who I’ve attached to them say more about me than it does the authors, but, whatever. ↩

-

“The determinative that is used to describe Israel as a ‘people’ does not suggest a disorganized body but rather one so pervasive as to occupy the entire interior of the hill country.” Eugene H. Merrill, Kingdom of Priests: A History of Old Testament Israel, Second Edition. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2008), 175. ↩

-

“The Israel of Merenptah’s stela was, by its perfectly clear determinative, a people (= tribal) grouping, not a territory or city-state…” K. A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2006), 451. ↩

-

“Poetic lines on this monument mention the conquest of the cities Ashkelon, Gezer, and Yenoam, as well as of Israel, which appears here (as a name of a tribe) for the first and only time in Egyptian sources.” Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible 10,000-586 B.C.E. (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 1990), 234. ↩

-

“The Merneptah stele refers to Israel as a group of people already living in Canaan.” Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman, The Bible Unearthed (Free Press, 2001), 60. ↩

-

“All Egyptologists are agreed that the names of Ashkelon, Gezer, and Yanoam refer to city-states in Canaan, as shown by the fact that the Egyptian scribe has attached to these what is called a “determinative sign,” that is, a sign that specifies what the place is. In these three instances, the sign is that for “three hills,” signifying lands outside the Nile Valley and the Delta. But the name Israel is followed by a different sign… which refers… to an ethnic group… The determinative sign in the Egyptian text is a gentilic, that is, one designating a specific people, and it is in the plural.” William G. Dever, Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2006), 202–203. ↩

-

“…the way Israel is introduced is different from the preceding place names, Canaan, Askalon, Gezer, and Yano’am. Israel alone is determined by the hieroglyphic sign for ‘foreign people’ something that may be taken as an indication of a different status of Israel in comparison to the other names on the inscription.” Niels Peter Lemche, The Israelites in History and Tradition (Westminster John Knox Press, 1998), 36-37. ↩

-

Robert D. Miller II, Chieftains of the Highland Clans: A History of Israel in the Twelfth and Eleventh Centuries B.C. (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2005), 94. ↩

-

e.g. “Because the Egyptian scribe used the people determinative it has been maintained that the Israel of the Merneptah stele cannot refer to a territory. I will argue that it refers to both.” Gösta W. Ahlström, “The origin of Israel in Palestine,” Scandinavian Journal of the Old Testament: An International Journal of Nordic Theology, Vol. 5, Issue 2 (1991), 23. ↩

-

William G. Dever, Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2006), 204–206. ↩

-

“The final portion of the text is a twelve-line poem of praise which complements the initial encomium. Where in the beginning the king had been lauded as the victor who freed Egypt from the Libyan menace, the concluding poem extols him as victor over all of Egypt’s neighbors, especially the peoples of Palestine and Syria. At the present time, scholars are wary of seeking historically accurate information in such triumphal poetry; hence one would hesitate to treat the poem as firm evidence for an Asiatic campaign of Merneptah.” Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume II: The New Kingdom (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973–), 73. ↩

-

Robert D. Miller II, Chieftains of the Highland Clans: A History of Israel in the Twelfth and Eleventh Centuries B.C. (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2005), 2. ↩

-

K. L. Noll, Canaan and Israel in Antiquity: An Introduction, vol. 83, The Biblical Seminar (New York: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001), 125–126. ↩

-

William G. Dever, Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2006), 206. ↩

-

Robert D. Miller II, Chieftains of the Highland Clans: A History of Israel in the Twelfth and Eleventh Centuries B.C. (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2005), 2. ↩

-

Michael G. Hasel, “Israel in the Merneptah Stela,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (November), no. 296 (1994): 51. ↩

-

William G. Dever, Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2006), 206. ↩

-

Michael G. Hasel, “Israel in the Merneptah Stela,” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (November), no. 296 (1994): 54. ↩