Joshua 10 and 11: Genre and hyperbole

In Jos 11:4 the northern coalition of Canaanites came to fight the Israelites with “a great army, in number like the sand on the seashore.“1 Now, pretty much no one on earth would take that description at face value. According to a group of researchers at the University of Hawaii2, there are roughly 7.5×10^18 grains of sand on all the beaches of the earth. That’s 75,000,000,000,000,000,000, or, seventy-five quintrillion grains. Even if we restrict ourselves to just the beaches of Canaan, taking that phrase at face value would demand a Canaanite army of billions upon billions.

This is obviously an example of hyperbolic language. Not even the most boneheaded literalist would think to take “in number like the sand on the seashore” at face value. But, what about passages that tell us that claim Joshua “took [Hebron], and struck it with the edge of the sword, and its king and its towns, and every person in it; he left no one remaining… (Jos 10:37)”? Should we take such passages at face value, or understand it as hyperbole?

On hyperbole

First of all, let’s see if we can help our fundamentalist friends who struggle with the idea of there being hyperbole in scripture. Some refuse to accept the notion because they believe that hyperbolic statements are “false” or “misleading”. They quote passages like “God… cannot lie” (Titus 1:2), and “The promises of the LORD are promises that are pure, silver refined in a furnace on the ground, purified seven times.” (Ps 12:6) to back up their claim.

Neither of those passages tell us anything about whether we should or should not expect to find hyperbole in scripture. Hyperbole isn’t lies, and it’s not somehow impure. It’s not false and it’s not misleading. It’s just exaggeration. Here are a few examples3 of passages from scripture that can only be hyperbole:

- the cities are large and fortified up to heaven (Dt 1:28)

- every one could sling a stone at a hair, and not miss (Jdg 20:16)

- the cry of the city went up to heaven (1 Sa 5:12)

- Saul and Jonathan, beloved and lovely! In life and in death they were not divided; they were swifter than eagles, they were stronger than lions. (2 Sa 1:23)

- If he withdraws into a city, then all Israel will bring ropes to that city, and we shall drag it into the valley, until not even a pebble is to be found there.” (2 Sa 17:13)

- And all the people went up following him, playing on pipes and rejoicing with great joy, so that the earth quaked at their noise (1 Ki 1:40)

- Judah and Israel were as numerous as the sand by the sea; they ate and drank and were happy. (1 Ki 4:20)

- I will strew your flesh on the mountains, and fill the valleys with your carcass. I will drench the land with your flowing blood up to the mountains, and the watercourses will be filled with you. (Eze 32:5–6)

- It is written, ‘My house shall be called a house of prayer’; but you are making it a den of robbers. (Mt 21:13)

- If I speak in the tongues of mortals and of angels, but do not have love, I am a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal. And if I have prophetic powers, and understand all mysteries and all knowledge, and if I have all faith, so as to remove mountains, but do not have love, I am nothing. If I give away all my possessions, and if I hand over my body so that I may boast, but do not have love, I gain nothing. (1 Co 13:1–3)

- How great a forest is set ablaze by a small fire! And the tongue is a fire. The tongue is placed among our members as a world of iniquity; it stains the whole body, sets on fire the cycle of nature, and is itself set on fire by hell. (Jas 3:5–6)

Hopefully that’s enough to make the point that, yes, scripture contains hyperbole, and plenty of it. God is recorded as employing the language of hyperbole, and the same goes for Jesus, David, Paul, and many others.

Hyperbole in comparative literature

We noted a few posts ago that Joshua 10 and 11 contain lots of hyperbole:

Who went with Joshua on the southern campaign? All the fighting force, all the mighty warriors (Jos 10:7). Who returned back to the camp? All Israel (Jos 10:15). Who did Joshua summon to the cave at Makkedah? All the Israelites (Jos 10:24). What happened to the people of Eglon? Every person was destroyed (Jos 10:35) – same goes for the rest of the towns. How much of the land did Joshua take on the Southern Campaign? The whole land (Jos 10:40). How quickly did Joshua take all these kings and their land? At one time (Jos 10:42). How big an army did Joshua face on the Northern Campaign? A great army in number like the sand on the seashore (Jos 11:4). How many of this vast army survived the battle with the Israelites? There were none remaining (Jos 11:8). How much did the Israelites take in spoil? All of it (Jos 11:14). How many of Moses’ commands did Joshua follow? All of them (Jos 11:15).

Let’s take a look at some comparative literature and see if we find the same thing in other conquest accounts. Spoiler: we do.

A long way in a short time

The conquest account of Joshua’s Southern Campaign ends with the following:

Jos 10:42 Joshua took all these kings and their land at one time, because the LORD God of Israel fought for Israel.

It would be wrong to claim, based on that verse alone, that the text says that the entire Southern Campaign happened in one day, but we do see that at least the initial Gilgal to Azekah/Makkedah section was meant to have happened in one day:

Jos 10:7–10 So Joshua went up from Gilgal, he and all the fighting force with him, all the mighty warriors… So Joshua came upon them suddenly, having marched up all night from Gilgal. And the LORD threw them into a panic before Israel, who inflicted a great slaughter on them at Gibeon, chased them by the way of the ascent of Beth-horon, and struck them down as far as Azekah and Makkedah.

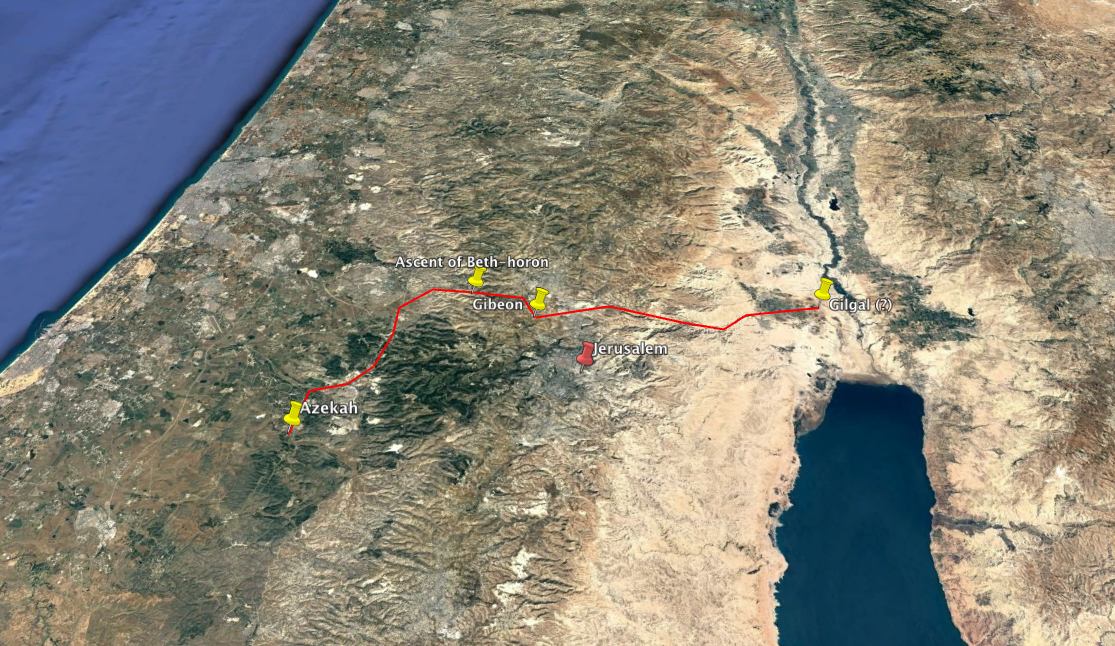

We’re not sure where Makkedah is located4, so we’ll concentrate on the Israelites’ journey as far as Azekah. Here it is on a map:

That’ a journey of 44.5 miles/71.5 km. And the record tells us that it happened in one day. Bear in mind a few things:

- We don’t know where Makkedah is, but they went there after that, so the day’s journey would have been longer than what the map indicates

- They began the journey at Gilgal which is around 400m below sea level, they went up to Gibeon which is around 770m above sea level, and then down the Ascent of Beth-horon (the same Beth-horon purportedly built by Ephraim’s granddaughter) to Azekah which is around 250m above sea level. So the Israelite army had altitude changes of almost 1.7 km; just over a mile

- They would have had to carry supplies of food and water

- Over the course of that one day the Israelites:

- Started with a forced early morning march from one of the lowest places on earth to one of the highest in Canaan

- When they arrived they fought a battle against a coalition of 5 armies

- They chased those who’d retreated down a long and steep canyon

- And continued picking them off over a distance of many miles of Canaanite country to Azekah

Walking 44 miles/71 km in one day would be an achievement in itself (particularly with such changes in altitude). But to throw in a few battles along the way, steep uphill night marches, and running down ravines many miles long shows us that we’re dealing either with something quite unusual (think Israelites travelling by hoverboard and fighting with lightsabers5), or we’re dealing with hyperbole.

The fundamentalist will invariably appeal to the miraculous. From experience, this is the sort of thing they come out with: “Well, God stopped the sun and moon on that day, so why couldn’t he have also zoomed the Israelites along? Isn’t it true that ‘With God all things are possible’?” Yes, yes they are. But just because miracles are possible doesn’t mean they actually happened in this instance. Constant appeal to miracles reminds me of this quote:

It is only in order to shield your ignorance that you put the Lord at every turn to the refuge of a miracle. – Galileo

Claiming that the Israelites miraculously actually did all those things that day tells us nothing about what happened, or about what the Bible says. It only tells us that the person who appeals to the miraculous doesn’t know how to read an ancient text. If we do take the time to investigate the comparative literature we’d find more claims of improbable distances covered in a single day.

In the Annals of Tiglath-Pileser I we find this:

With the help of Assur, my lord, I led forth my chariots and warriors and went into the desert. Into the midst of the Ahlami, Arameans, enemies of Assur, my lord, I marched. The country from Suhi to the city of Carchemish, in the land of Hatti, I raided in one day. I slew their troops; their spoil, their goods and their possessions in countless numbers, I carried away.6

Oh really, Tiglath? Suhi7 is in the middle Euphrates region south of Mari; Carchemish is on the modern border of Syria and Turkey. So if we take Tiglath’s words at face value then he travelled hundreds of miles in a single day, battling his Aramean enemies along the way. Unless we believe the Assyrians also had hoverboards and lightsabers8 we can safely conclude that this didn’t happen. But, Tiglath-Pileser’s claim that he did all that in one day is right there in the annals. Just like it’s there in Joshua.

It’s hyperbole in the Annals of Tiglath-Pileser I9, and it’s hyperbole in the conquest accounts of Joshua 10 and 11.

Although we’ve only looked at one example from the comparative literature there are plenty of others we could have looked at. But we’ve got a fair bit to cover so we’re going to move on. Take a look at the resources mentioned in the Further reading section below if you want more.

The nations conquered

Which nations did the Israelites conquer? All of them:

Jos 10:40–42 So Joshua defeated the whole land, the hill country and the Negeb and the lowland and the slopes, and all their kings; he left no one remaining, but utterly destroyed all that breathed, as the LORD God of Israel commanded. And Joshua defeated them from Kadesh-barnea to Gaza, and all the country of Goshen, as far as Gibeon. Joshua took all these kings and their land at one time, because the LORD God of Israel fought for Israel.

But, as we’ve seen, the rest of scripture doesn’t line up with that. In fact, had the above actually happened the history of the Israelites in the Judges and early monarchy periods would have been radically different. As we saw in the first post in this series, a quick read of Judges 1-3 will show that the passage quoted above cannot be taken at face value. And, if it can’t be taken at face value, it must be exaggeration.

By now in this series we shouldn’t be surprised to find that comparative literature contains the same sort of thing. Let’s take a look at an example – the Merneptah Stele we looked at in a previous post.

Pharaoh Merneptah (1213-1203 BCE) went on a campaign to the Levant and recorded his conquests on a stele – a large stone slab – that today stands in the Museum of Egyptian Antiquities. Here’s what it says:

The princes are prostrate, saying: “Mercy!” Not one raises his head among the Nine Bows. Desolation is for Tehenu; Hatti is pacified; Plundered is the Canaan with every evil; Carried off is Ashkelon; seized upon is Gezer; Yanoam is made as that which does not exist; Israel is laid waste, his seed is not; Hurru is become a widow for Egypt! All lands together, they are pacified; Everyone who was restless, he has been bound by the King of Upper and Lower Egypt.10

When we first looked at this inscription we noted that it claims Israel, contrary to what we know, were annihilated. This time, let’s look at the second line quoted above: Not one raises his head among the Nine Bows.

The Nine Bows is an Egyptian collective term for all their enemies.11 So, what Merneptah claims in this inscription is that, like Joshua, he’d conquered all his enemies. Given the facts of the matter –he hadn’t conquered all this enemies– Merneptah is plainly employing hyperbole in his conquest account. That’s no surprise; it’s how conquests (or attempts at conquest!) were recorded across the ancient Near East.

Huge enemy armies

To come back to the verse we started with…

Jos 11:4 They came out, with all their troops, a great army, in number like the sand on the seashore, with very many horses and chariots.

“Like the sand on the seashore.” Clearly hyperbole, as we established at the top of this post.

We find similar claims of massive armies in comparative literature. Our first example comes from the Poem of Rameses II’s battle at Kadesh:

Now the vile Foe from Khatti had come and brought together all the foreign lands as far as the end of the sea. The entire land of Khatti had come, that of Nahrin also, that of Arzawa and Dardany, that of Keshkesh, those of Masa, those of Pidasa, that of Irun, that of Karkisha, that of Luka, Kizzuwadna, Carchemish, Ugarit, Kedy, the entire land of Nuges, Mushanet, and Kadesh. He had not spared a country from being brought, of all those distant lands, and their chiefs were there with him, each one with his infantry and chariotry, a great number without equal. They covered the mountains and valleys and were like locusts in their multitude.12

A bit further into the poem we find this:

Now the vile Chief of Khatti stood in the midst of the army that was with him and did not come out to fight for fear of his majesty, though he had caused men and horses to come in very great numbers like the sand — they were three men to a chariot and equipped with all weapons of warfare — and they had been made to stand concealed behind the town of Kadesh.13

So, we find not just the same claim of armies massive beyond counting, they make the point using the same language, “like the sand”.

It’s only in movies that find such massive armies, yet, ancient conquest accounts mention them frequently.

Conclusion

So, as we’ve seen, ancient conquest accounts are filled with hyperbole. They describe huge armies, complete conquests, quick travel over impossibly long distances, annihilation of enemies, and instantaneous victories. When we read Joshua 10 and 11; being ancient conquest accounts they are no different – they claim the same improbable things.

Clearly, conquest accounts filled with hyperbole don’t fit what we expect from narrative history. But the problem isn’t the hyperbole, it’s our expectations. If we expect Joshua 10 and 11 to be written like modern historical narrative then they’ll make little sense. But, if we accept that the scriptures are old and written a very long time ago in the genres of the day then it’s no surprise that our chapters look just like conquest accounts of their day. And why wouldn’t they? The audience they were written for was so foreign to us that they may as well be aliens. To expect their conquest accounts to look like our narrative histories seems mighty odd.

In the next post we’ll cover what for me is the most intriguing aspect of Joshua 10 and 11: their common narrative structure. We’ll take a look at the order they follow and compare it with the comparative literature. The results are quite surprising…

Further reading

- K. Lawson Younger Jr., Ancient Conquest Accounts: A Study in Ancient Near Eastern and Biblical History Writing (vol. 98; Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1990)

- On the refusal to accept that scripture could contain hyperbole, see “The Intellectual Disaster of Fundamentalism” in Mark A. Noll, The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1994), 109–145.

Featured image

The sandy beach at Tel Dor, Israel.

Footnotes

-

All scripture quotations unless otherwise noted are from the New Revised Standard Version (Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1989) ↩

-

https://web.archive.org/web/20131218195759im_/http://www.hawaii.edu/suremath/images/sand.GIF ↩

-

Many more can be found in Ethelbert William Bullinger, Figures of Speech Used in the Bible (London; New York: Eyre & Spottiswoode; E. & J. B. Young & Co., 1898), 423–428, and Grant R. Osborne, The Hermeneutical Spiral: A Comprehensive Introduction to Biblical Interpretation (Rev. and expanded, 2nd ed.; Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2006), 127. ↩

-

“All that we can say for certain is that the biblical passages support a location somewhere in the central or N Shephelah, in the vicinity of Azekah (Josh 15:10) and Lachish (Josh 15:41). Attempts to locate Makkedah farther to the S and E (Noth 1937) ignore these geographical hints and depend too heavily on the speculations of Eusebius.” Wade R. Kotter, “Makkedah (Place),” ed. David Noel Freedman, The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 478. ↩

-

Sadly I cannot supply a picture – Google image search has failed me ↩

-

Daniel David Luckenbill, Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia (Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 1926), 83. ↩

-

Or “Suhu”/”Suhum” if you want to google it ↩

-

Or that God performed a miracle for them too… ↩

-

“One can see how the phrase ina ištēn ūme :: ‘in a single day’ is used here in a hyperbolic sense for the distance between Suhu (on the middle Euphrates) to Carchemish (in northern Syria) is very great to traverse in a single day.” K. Lawson Younger Jr., Ancient Conquest Accounts: A Study in Ancient Near Eastern and Biblical History Writing (vol. 98; Journal for the Study of the Old Testament Supplement Series; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1990), 216. ↩

-

James Bennett Pritchard, ed., The Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (3rd ed. with Supplement.; Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1969), 378. ↩

-

John L. Foster and Susan T. Hollis, Hymns, Prayers, and Songs : An Anthology of Ancient Egyptian Lyric Poetry (vol. 8; Writings from the ancient world; Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1995), 197. ↩

-

Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume II: The New Kingdom (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973–), 64. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩