Israelite Origins: the Late Bronze Age collapse

At around 1200 BCE, during what is now seen as the transition from the Late Bronze Age to the Iron Age, the eastern Mediterranean world suffered mass societal collapse. In his excellent 1177 B.C. The Year Civilization Collapsed Eric Cline sums up just how serious the chaos was:

The magnitude of the catastrophe was enormous; it was a loss such as the world would not see again until the Roman Empire collapsed more than fifteen hundred years later.1

Far from being a few squabbles between some knuckle-dragging savages on the edge of some desert somewhere, the Late Bronze Age collapse resulted in the disintegration of international trade, the end of dynasties, and an entirely new world order prompted by mass migration.

Far over the sea from Canaan, the Mycenaean civilization suffered a systems collapse that began its Dark Ages. Osborne writes:

The Mycenaean world ended with a bang and a whimper. Around 1200 BC several of the major Mycenaean centres in the Peloponnese and in central Crete show signs of violent destruction, fire, or abandonment.2

There were two main results of this chaotic period in Greece. The first is a contraction. As Osborne continues, “…no big buildings, no multiple graves, no impersonal communication, limited contact with a wider world… not only the political units, but also the whole social and economic organization broke up”.3 This enlightened corner of a previously cosmopolitan Mediterranean world became a rural backwater.

The second big effect of the Mycenaean collapse was the migration of a large portion of its people eastward to places like Cyprus4, but also to Hittite lands across the Aegean sea:

Towards the end of the second millennium, boatloads of travellers from mainland Greece began making landfalls along Anatolia’s western coast. They were not warriors but family groups who had departed their homelands, perhaps to escape troubled conditions there following the collapse of the major centres of power in the Greek world at the end of the Bronze Age.5

The Hittite civilization was not spared in the Late Bronze Age collapse. Their capital Hattusa, was captured, plundered, and razed.6 Before this, the Hittite empire had been in decline. It had suffered repeated attacks from outside its borders, internal rebellion, secession, and famine.7

Collins writes that the famine had caused the tribute of Hittite vassals to increase dramatically and that,

The resulting inflation, combined with food shortages, meant that its people were forced to sell their children… It probably took years, but the dam finally broke, and starving peasants abandoned their villages in droves to seek more favorable conditions by land or sea.8

The effects of this societal collapse were extraordinary. Collins goes on to explain that,

Moreover, the south-coastal regions of Anatolia –Caria, Lycia, and Cilicia– were notorious for their piratical activities… The famine that ravaged Anatolia probably turned these scattered raids into vast population movements involving not disenfranchised militants on a pillaging rampage but entire families turned to a marauding lifestyle in the search for new places to settle. For the most part a disorganized and heterogeneous collection of peoples, they were as much victims of as they were contributors to the circumstances that brought the Bronze Age in the Near East to an end.9

Just as had been the effect of the Mycenaean collapse, the Hittite people began mass migration as a result of the end of their civilization.

To the south of the Hittites, Ugarit, a shining beacon of Late Bronze Age culture, did not escape. Writing of those responsible for the end of Ugarit, today are referred to as the “Sea Peoples”, Yon explains they “were probably groups of invaders from the north-west who attacked [Ugarit] in several waves over a period of years.”10 The outcome of this was,

…the kingdom and its culture simply collapsed under this pressure, never to be revived. The capital… was seized, set ablaze, and abandoned. The political and administrative structures linked to the royal power did not survive the capital, and the government and civilization disappeared.11

Further south again, these same Sea People first attacked the Nile delta around 1208 BCE, during the reign of Pharaoh Merneptah (of the oft-mentioned Merneptah Stele).12 Over the next 30 years or so wave after wave of this new enemy arrived on Egypt’s shore.

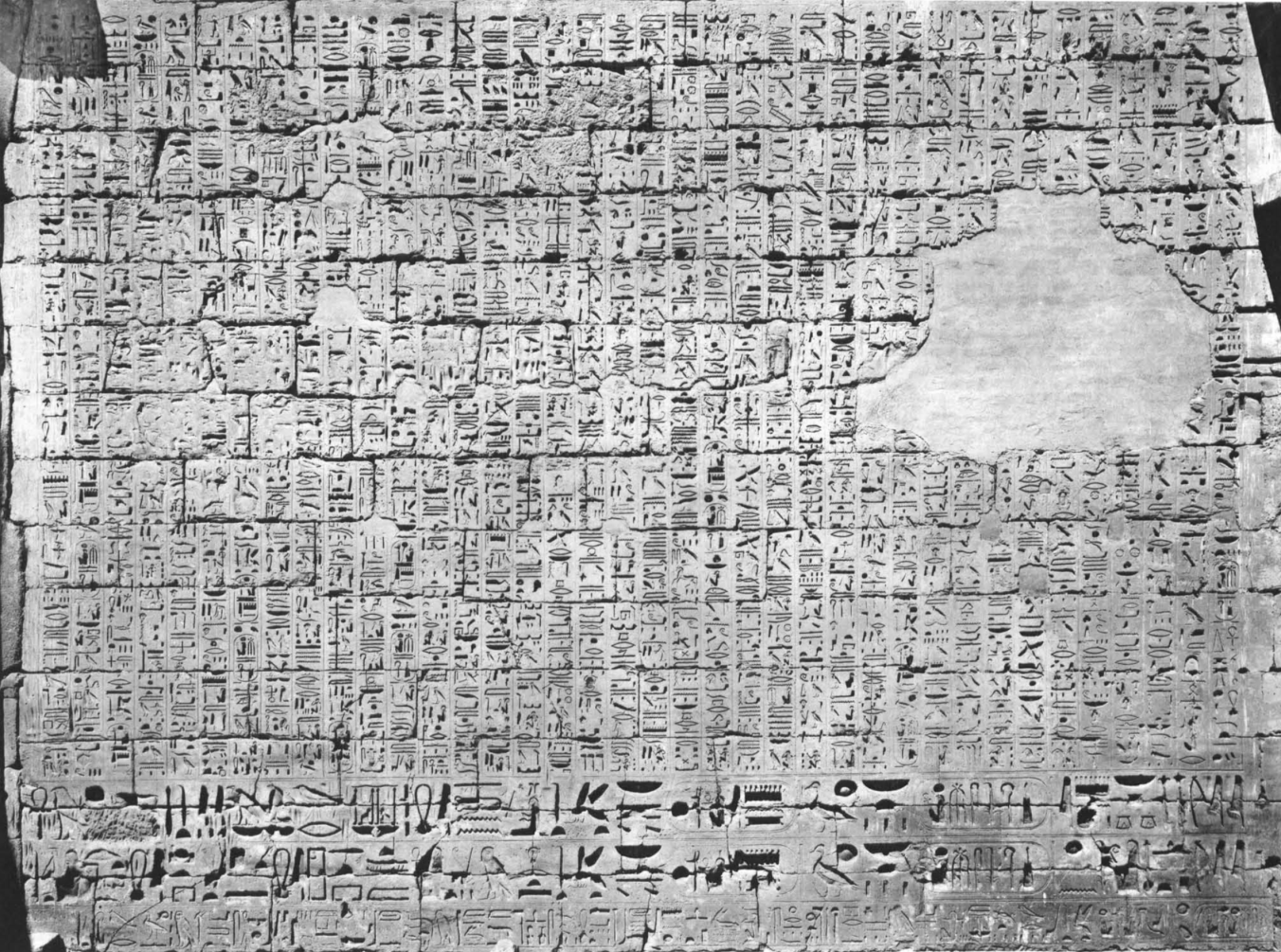

The Year Eight Inscription of Ramses III13

The Year Eight Inscription of Ramses III13

Ramses III in his Year 8 inscription recalls his victory over the Sea People, describing how his enemy had decimated many places before suffering defeat when they landed on Egypt’s doorstep. He didn’t know where the Sea People had come from, but Ramses III did know the names of their tribes, recording them in inscriptions at Karnak:

As for the foreign countries, they made a conspiracy in their isles. Removed and scattered in the fray were the lands at one time. No land could stand before their arms, from Hatti, Kode, Carchemish, Yereth, and Yeres on, (but they were) cut off at [one time]. A camp [was set up] in one place in Amor. They desolated its people, and its land was like that which has never come into being. They were coming, while the flame was prepared before them, forward to Egypt. Their confederation was the Peleset, Theker [or Tjekel], Shekelesh, Denyen, and Weshesh; lands united. They laid their hands upon the lands to the very circuit of the earth, their hearts confident and trusting. ‘Our plans will succeed!’14

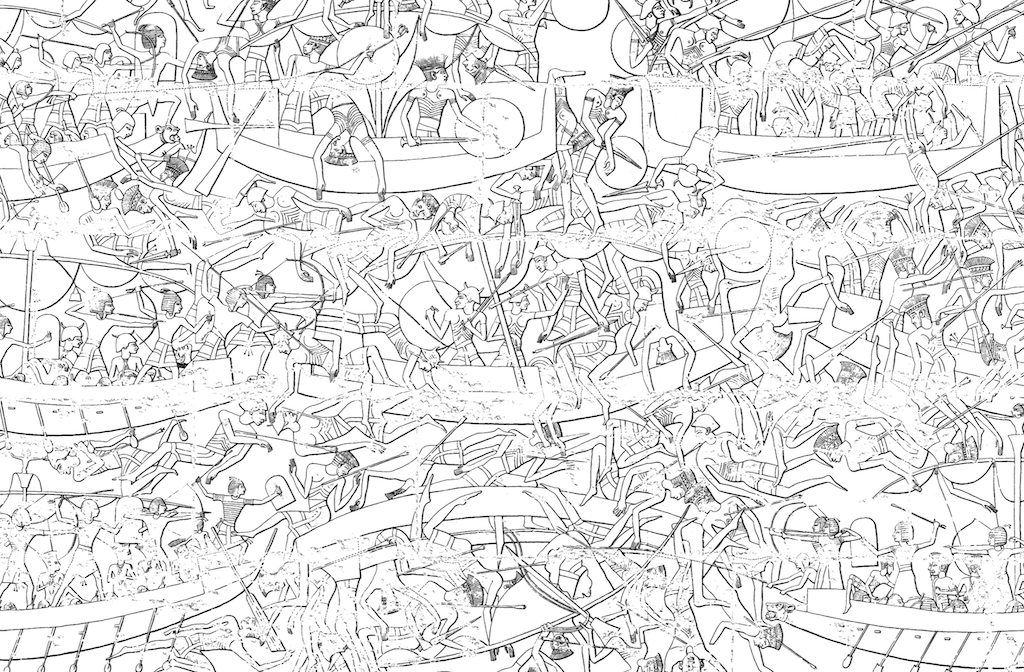

Next to this inscription are reliefs depicting the event. They portray the Sea People, specifically the tribe known as the Peleset, in sea battles with the Egyptians.15

Sea battle between the Egyptians and the Peleset16

Sea battle between the Egyptians and the Peleset16

Though Ramses III recorded this event as a complete victory over the Sea People, the reality was a little different:

Although the wars against the Sea Peoples during the days of Ramesses III, early in the twelfth century B.C.E., were concluded with no immediate effect on Egyptian power, this invasion might have had deeper implications and, together with internal factors, possibly brought about the end of the Egyptian New Kingdom.17

The truth of the matter is that repulsing the Sea People had drastically reduced Egypt’s strength.18 Redford writes:

Within fifteen years of the passing of Ramesses III, Egyptian control of its former northern dependencies had been lost…19

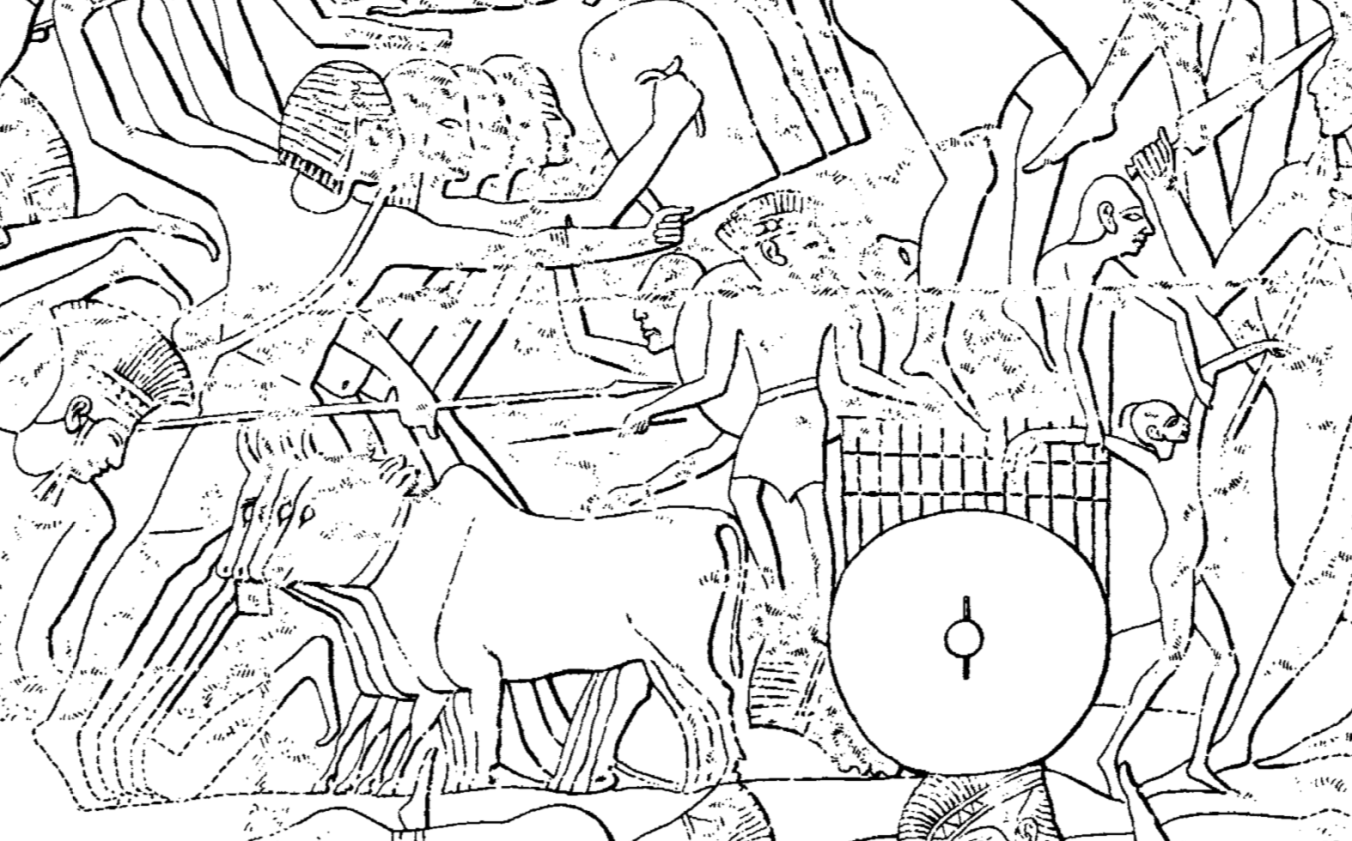

If we look carefully at the Karnak reliefs that depict the battles between the Egyptian forces and the Peleset we will notice that the Peleset warriors weren’t alone. With them on ox-drawn carts were their women, children, and possessions. This was no ordinary raid we’re looking at – this is a displaced people looking for somewhere to settle.

Ox-drawn cart carrying the women and children of the Peleset Sea People in the thick of battle20

Ox-drawn cart carrying the women and children of the Peleset Sea People in the thick of battle20

After their defeat at the hand of Ramses III these displaced Sea People found exactly what they were looking for on the Mediterranean coast east of Egypt. The Sherden, Tjekel, and Peleset Sea People settled themselves in Canaan21, but Ramses III later claimed to have settled them there himself, as we read in in what is today known as Papyrus Harris:

I extended all the boundaries of Egypt; I overthrew those who invaded them from their lands. I slew the Denyen in their isles, the Thekel and the Peleset were made ashes. The Sherden and the Weshesh of the sea, they were made as those that exist not, taken captive at one time, brought as captives to Egypt, like the sand of the shore. I settled them in strongholds, bound in my name. Numerous were their classes like hundred-thousands. I taxed them all, in clothing and grain from the storehouses and granaries each year.22

It seems that these tribes organised themselves along the same lines as they had been back where they’d come from:

Their pentapolis included the cities Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod, Gath (apparently Tel Safit [Tell es-Safi]), and Ekron (Tel Miqne); it seems to have comprised a coalition of city-states similar to that found in Bronze Age Greece.23

Their political setup along with the evidence of the change in pottery style betrays the Mycenaean origin of the Peleset24, or, as they are better known, the Philistines.25 Though culturally the Philistines assimilated with their Canaanite neighbours within a matter of a few generations26, for the next few hundred years they remained a distinct group and were a constant source of problems for the Israelites.

So, there’s a quick overview of the Late Bronze Age collapse and the arrival of the Philistines in Canaan. What’s the significance to the topic of Israelite origins? Well, as we saw in the previous post, Canaan for around three centuries was a playground for Egypt. It had been partly depopulated, few of its towns had defensive walls, and its petty kings put in place by Egypt crawled at Pharaoh’s feet. Egypt ruled Canaan with an iron fist.

The arrival of the Sea People on the Nile delta put the previously unassailable Egyptian army on the back foot. Forced to defend herself against wave after wave of invasion Egypt had little spare time to maintain the empire it had built up – Egyptian influence in Canaan began to decline. Retreating home from Canaan the Egyptian forces left a power vacuum in their wake, a vacuum that allowed smaller powers to emerge and control territories and kingdoms of their own.

In the next post we’ll take a look at the archaeological evidence for the origin of one of these new groups that emerged out of the vacuum left by the retreating Egyptians – the Israelites. Previously little more than a footnote on the Merneptah Stele we’ll see them go through what one scholar describes as a ‘population explosion’27, the evidence for which is called the Israelite Settlement. More next time.

Further reading

- Eric H. Cline, 1177 B.C. The Year Civilization Collapsed (Princeton University Press, 2014)

- Donald B. Redford, “The Coming of the Sea Peoples”, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times (Princeton University Press, 1992), 241-256.

And this really is mandatory watching:

Featured image

Standing at the edge of Tel Dor at the beginning of a storm that lasted, on and off, for 3 days.

Footnotes

-

Eric H. Cline, 1177 B.C. The Year Civilization Collapsed (Princeton University Press, 2014), xviii. ↩

-

Robin Osborne, Greece in the Making, 2nd ed. (London and New York: Routledge, 2009), 35. ↩

-

Ibid., 46. ↩

-

Ibid., 38. ↩

-

Trevor Bryce, The World of the Neo-Hittite Kingdoms (Oxford University Press, 2012), 33. ↩

-

Philo H. J. Houwink ten Cate, “Hittite History,” ed. David Noel Freedman, The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 222. ↩

-

Billie Jean Collins, The Hittites and their World (Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2007), 76. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid., 77. ↩

-

Marguerite Yon, The City of Ugarit at Tell Ras Shamra (Eisenbrauns 2006), 21. ↩

-

Ibid., 22. ↩

-

Ian Shaw, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt (Oxford University Press, 2000), 322. ↩

-

James Henry Breasted, Medinet Habu Volume I – Earlier Historical Records of Ramses III (University of Chicago Press, 1930), pt. 45. ↩

-

Edgerton & Wilson, Historical Records of Ramses III – The Texts in Medinet Habu Volumes I and II (Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 1936), 53. ↩

-

Donald B. Redford, Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times (Princeton University Press, 1992), 251. ↩

-

James Henry Breasted, Medinet Habu Volume I – Earlier Historical Records of Ramses III (University of Chicago Press, 1930), pt. 37 ↩

-

Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible 10,000-586 B.C.E. (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 1990), 287. ↩

-

“…the victory Ramesses lays claim to may not have been as complete as he would wish to have us think…” Redford, op. cit., 255. ↩

-

Redford, op. cit., 290. ↩

-

James Henry Breasted, Medinet Habu Volume I – Earlier Historical Records of Ramses III (University of Chicago Press, 1930), pt. 34 ↩

-

Mazar, op. cit., 305. ↩

-

Papyrus Harris, 76.403. James Henry Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt Volume IV (University of Chicago Press, 1906), 201. ↩

-

Mazar, op. cit., 306. ↩

-

Mazar, op. cit., 306–307. ↩

-

Ludwig Koehler et al., The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1994–2000), 936. ↩

-

“Isolated from the source of their culture, the Philistines were inspired by the indigenous population and were assimilated into it. This was a long and gradual process.” Mazar, op. cit., 328. ↩

-

William G. Dever, Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2006), 98. ↩