Israelite Origins: The Song of Deborah

When attempting to glean historical information from the biblical text we should employ the utmost caution. As Kofoed explains,

All sources, primary/secondary and firsthand/secondhand, need to be checked for ideological, propagandistic, religious, or other biases before the encoded historical information can be used for historiographical purposes.1

The biblical text as it exists today is not only an expression of those biases, it is also, in the main, written much later than the events it describes. To take the example of the biblical book that we’re going to be concentrating on in this post, Judges, at least in its final form, is aware of the Assyrian captivity that took place in 720 BCE.2

Jdg 18:30 Jonathan son of Gershom, son of Moses, and his sons were priests to the tribe of the Danites until the time the land went into captivity.

The book therefore took its final form at the very earliest around 500 years after some of the events it describes (i.e. the conquest of the land beginning in Judges 1 describes events that were meant to have taken place in around 1200 BCE). So, caution is warranted.

This is not to say that everything in the book is late, nor are we saying that its contents were spun out of whole cloth. Far from it. On the writers of the book of Judges, Mobley writes,

These historians did not begin from scratch but utilized older poems and stories, annalistic records from the courts of Israelite and Judean kings, genealogical records, oddly shaped bits of ancient royal administrivia, lists of geographical boundaries and of officials, legends about prophets, and priestly teachings, many of which must have already been shaped into literary documents.3

There is therefore a considerable amount of ancient history woven throughout the Deuteronomistic History (the books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings). As Bloch-Smith and Nakhai write,

While the Hebrew Bible is an unabashedly theological document that must be used with great caution for historical purposes, it remains a valuable—but not infallible—resource for documenting Israelite perceptions of ethnic affiliation.4

If we’re careful about it we can extract a lot of information that can help us build a picture of just how the Israelites emerged in Canaan. And, in this post, that’s exactly what we’re going to do with Judges 5.

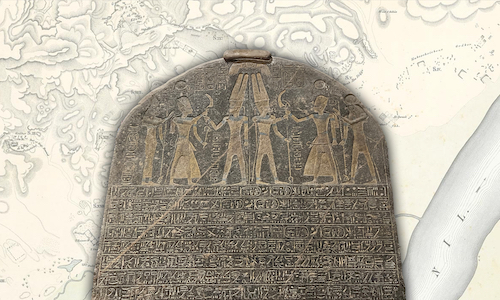

The Battle at the Waters of Megiddo

The Song of Deborah recorded in Judges 5 records a battle between Israelites and “the kings of Canaan, at Taanach, by the waters of Megiddo” (Jdg 5:19) in the period of the Judges, in the days when “there was no king in Israel”. Given the Israelites emerged around 1200 BCE and the monarchy began around 1000 BCE, if the event recorded in the Song “happened”, then it happened somewhere in this 200 year period. But, can we get any more specific?

The song locates the battle at Ta’anach (v19). Ta’anach was a small hilltop village that was destroyed around 1125 BCE and then lay desolate for more than 100 years.5 If the fact that Ta’anach comes first in the song indicates its relative importance to Megiddo at the time, as Malamat suggests, this might indicate that that mighty city lay in ruins at the time the battle took place.6 Given Megiddo has an occupation gap between around 1130 and 1100 BCE7, the battle at Ta’anach might be able to be dated to approximately 1130-1125 BCE.

Dating (the song of) Deborah

It has long been thought that the Song of Deborah, preserved in Judges 5:1-31, is truly ancient, dating back to Iron Age I – the earliest Israelite period. For example, more than a century ago, back in 1910, George F. Moore wrote that,

It is the oldest extant monument of Hebrew literature, and the only contemporaneous monument of Hebrew history before the foundation of the kingdom.8

This is view of Judges 5 has survived the test of time. For example, in the Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary Boling writes,

The Song of Deborah and Barak (5:1–31) is a priceless piece of archaic Hebrew poetry which offers direct access to religion and polity of the Yahwist organization in the late 12th–early 11th centuries B.C.E.9

You read that right: the late 12th to early 11th centuries BCE. So, some time around 1100 BCE.

So, what is this dating based on? Basically, the language of the song. It’s time for a quick overview of the history of biblical Hebrew…

Using English translations of the Bible it’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking that the uniform English we read represents a uniform Hebrew beneath it. What’s actually the case is that different phases of the development of the Hebrew language are represented in different places in the Hebrew Bible. If we could flip the situation on its head we’d have a modern Hebrew book translated from modern English texts, some Charles Dickens, some Elizabethan texts, a bit of Chaucer, and a few lines of Beowulf. The modern Hebrew would “hide” the variation seen across the various original English texts. That’s kinda what’s going on in our English translations, just in reverse.

Broadly speaking there are three main phases of Hebrew represented in the biblical text10:

- Early Biblical Hebrew

- Examples: Gen 49, Exod 15, Num 23–24, Deut 32 & 33, Judg 5, 1 Sam 2, 2 Sam 1, 22, & 23, Pss 18, 29, 68, 72, and 78, Hab 3

- Standard Biblical Hebrew, found in:

- Narrative portions of the Pentateuch

- Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings

- Pre-exilic materials in the prophets and writings

- Late Biblical Hebrew, found in:

- Ezra—Nehemiah, Esther, 1–2 Chronicles, Ecclesiastes, Daniel

Early Biblical Hebrew is distinguished from later phases by its use of linguistic features that mark it as ancient. Given that my Hebrew is only just good enough to order falafel and ask directions to the beach, I’m not going to start pontificating about what those features are. I’ll just cherry pick a few sentences from Frank Moore Cross and David Noel Freedman’s Early Yahwistic Poetry:

The body of poetry which comes from early Israelite times is distinguished by characteristic archaisms. In the morphology of the verb a number of archaic forms have been isolated. One of the more important is the so-called t-form imperfect used with duals or collectives. It was first identified in the Ugaritic literature, and subsequently in the Amarna correspondence and Israelite poetry…

The energic nun was a living form in ancient Yahwistic poetry. It occurs in all imperfect forms, and not only, as in later Hebrew, in plural forms in -û, or before pronominal suffixes…

In addition there are a number of isolated archaic forms such as ša-qamtî (Jud. 5:7), a second person feminine singular; or a possible infixed-t form in Deut. 33:3.

The most striking feature of the morphology of the noun is the frequent preservation of old case endings. The survival of the case endings is due in almost every case to clear-cut metrical requirements…

The persistence of archaic forms of the pronominal suffixes is another feature of the old poetry. The regular use of -mô -mû < -himmū̆) in Ex. 15 is a parade example…

The survival of the longer forms of the pronominal suffixes (e.g., -kā̆ // -k; -kī̆ // -k; hēmmâ // hēm) was due in part at least to metrical considerations…

The old poems preserve a number of particles which exhibit archaic features. Thus there is the use of the preposition b in the sense “from” (= min) as in Ugaritic…

Quite common in these studies is the use of the enclitic -m (= mi of the Amarna letters and Ugaritic texts). The enclitic -m may appear with prepositions (e.g., ’ittô-m, Deut. 33:2), with a noun in the absolute state (e.g., ’ēl-m, Num. 23:22), with a noun in the construct state (e.g., motnê-m qamîw, Deut. 33:11, and ’apîqî-m yām, 2 Sam. 22:16 = Ps. 18:16), and with verbs (e.g., תמלא־ם and תרש־ם in Ex. 15:9).

The syntax of the verb in ancient Yahwistic poetry (especially the use of qtl and yqtl forms) corresponds much more closely to that of Ugaritic poetry than to Hebrew prose or later poetry…11

TL;DR: Basically, Early Biblical Hebrew is distinguished from Standard and Late Biblical Hebrew by its ancient spelling, grammar, and similarities with Ugaritic literature. If you want more detail you could start with William M. Schniedewind’s A Social History of Hebrew – Its Origins through the Rabbinic Period.1213

You’ll have noticed above that Judges 5 is categorised as being written in Early Biblical Hebrew. But it’s not just “early”…

According to the experts the song is not just Early Biblical Hebrew – it competes only with the Song of the Sea in Exodus 15 for being the earliest of the Early Biblical Hebrew sections of scripture.14

So, just how old is the Song? Frank Moore Cross and David Noel Freedman write that it is,

a victory hymn, the occasion of which is known, and the approximate date quite certain, i.e., ca. 1100 B.C.15

In a surprising twist, the consensus view of modern scholars dates the song to an earlier period than traditional views would. As we’ve seen, modern scholarship dates the written form of the song to the 12th/11th centuries BCE, but the Talmud, in Baba Batra 14b16, explains that “Samuel wrote the book that is called by his name and the book of Judges and Ruth”. That’s about 100 years later than the modern view – a phenomenon that doesn’t happen all that often.

And, just how close in time to the events described in the song was it written? Brown sums up the majority position,

Some scholars believe that it, or part of it, is contemporaneous with the events themselves, while others suggest that it was composed within a generation of the events it celebrates.17

And that’s what’s important about Judges 5. It’s a text from the early Israelite period that, as quoted above,

…offers direct access to religion and polity of the Yahwist organization in the late 12th–early 11th centuries B.C.E.18

As Gottwald wrote,

In the Song of Deborah there are obviously direct and detailed reminiscences.19

Embedded in the song is material that can inform us about the nature of early Israel. It’s the oldest textual evidence for the period and can be mined for useful information.

However…

As mentioned at the beginning of this post, we must be cautious. We can’t just take the poem at face value expecting it to be history writing in the sense we know and use today. Sasson sums up the situation we find ourselves in when trying to extract historical information from the song:

While its context is clearly linked to a glorious victory, the contents of the poem break away from servile devotion to what may have transpired. Its sentiments range broadly, its expressions turn hyperbolic, its voice fractures and multiplies, its gaze becomes intimate, its vision cosmic, and its posture judgmental.20

Yes, I’m labouring the point. But the point is important. Though this song is from the earliest Israelite period it is not plain historical narrative. It’s way more interesting than that.

OK, that’s enough caveats and caution.

Just Pharaoh doing Pharaoh…

One final thing on dating before we go on. As has been mentioned previously in this series, Egypt dominated Canaan until the mid-late 12th century; a problem for both Late Date and Early Date Exodus/Conquest people. The point we made back in that post was that since at no point in Joshua or Judges is that Egyptian domination mentioned, the historical value of the narratives in those books must be called into question. However…

There is one possible clue embedded in Judges 5 potentially mentioning that Egyptian domination. The first couplet in the song is notoriously hard to translate. Here’s a translation review demonstrating the point:

- NRSV: When locks are long in Israel, when the people offer themselves willingly

- Butler, WBC21: When the tresses flow freely in Israel, when the people offer themselves freely

- Boling, AYB22: When they cast off restraint in Israel, when the troops present themselves

- ESV23: That the leaders took the lead in Israel, that the people offered themselves willingly

- NIV 2011: When the princes in Israel take the lead, when the people willingly offer themselves

- Sasson, AYB24: For seizing leadership in Israel, for people in full devotion

The reason for this wide variety of translations is explained succinctly in the Jewish Study Bible: the Hebrew is difficult.25 “The meanings of the words have escaped translators.”26 We’re dealing with a difficult text.

Miller’s view is that בִּפְרֹעַ פְּרָעוֹת (translated “When locks are long” in the NRSV) should be translated “When the Pharaohs pharaohed”, or, more meaningfully “When the pharaohs ruled.”27 If the verse indeed mentions Pharaohs “pharaohing” in Canaan, then it would seem that the first verse of the song “provides a date formula that situates the events of the song.”28 i.e. the Song is about an event that can be dated to the period around 1140 BCE when Rameses IV finally pulled out of Canaan.29 Miller’s view hasn’t been taken up much in the scholarship yet, so we’ll not place too much stock by it. However it’s pretty recent so it’s one to watch.

There’s much in the song that we could look at, but we’re going to restrict our focus to what the late Lawrence Stager refers to as “social archaeology.”

Who came to the battle?

On the reliability of the historical setting of the song, Stager, in his award winning30 article, The Song of Deborah — Why Some Tribes Answered the Call and Others Did Not, wrote that,

…whether or not it is historically accurate in every detail, the poet, in order to achieve verisimilitude, must have grounded the story in a setting and in circumstances that seemed plausible to the contemporary audience for which the poem was intended.31

At least to this layman, this reasoning makes a whole lot of sense. As far as the topic of Israelite origins goes, we’re interested in what the song can tell us about who was on Deborah and Barak’s side in the battle at the Waters of Megiddo.

During the course of the song, Deborah praises tribes that turned up for the battle, and others that didn’t. The tribes that answered Deborah’s call were:

- Ephraim

- Benjamin

- Machir (most likely standing for Manasseh32, see Nu 26:29, Jos 13:31 & 17:1)

- Zebulun

- Issachar

- Naphtali

Tribes that didn’t answer the call:

- Reuben

- Gilead (very likely a reference to Gad33, see 1 Sam 13:7)

- Dan

- Asher

Firstly, Deborah seems to have expected all of the above named tribes to have turned up to help in the battle. It seems reasonable to assume there to have been at least a loose alliance between those tribes; an alliance that included people groups on both sides of the Jordan valley.

Secondly, the names are very familiar to anyone with even a passing knowledge of the story of Jacob in Genesis – there’s a great degree of overlap between the tribes listed in Judges 5 and the names of the sons of Jacob in Genesis 29-30.

Thirdly, for three of the four tribes that are mentioned as failing to turn up to battle we’re given geographical clues about where they lived. The locations match up well with what we’re told about those tribes’ “allotments” in Joshua 13-1834:

| Tribe | Geographical description in Judges 5:17 | Tribal allotment | Other relevant passages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gilead (Gad) | “Stayed beyond the Jordan” | East of the Jordan: from Heshbon in the south, running up the Jordan valley to the Sea of Galilee, an eastern arm went as far north as Ramoth Gilead, but only as far as Mahanaim in the central hilly section/western plateau (Joshua 13:24–28) | 1 Samuel 13:5, Jeremiah 49:1–6 |

| Dan | “Why did he abide with the ships?” | Small portion of modern Israel’s coastal plain including a section of the coast south of modern Tel Aviv (Joshua 19:40–46) | Judges 13:2, Judges 18:2 |

| Asher | “Sat still at the coast of the sea, settling down by his landings” | The coastal stretch between Mt Carmel in modern Israel to Sidon in modern Lebanon (Joshua 19:24–31) | Judges 1:31 |

However poetic the language may be, that’s a remarkable correspondence.

Fourthly and finally, there are missing tribes. Let’s take a quick look at that.

When we think of the tribes of Israel, we normally think of them as the people that descended from Jacob’s 12 sons. As we’ve already mentioned, there’s significant overlap between Deborah’s tribes and the eponymous sons of Jacob. However, if we were expecting all 12 sons to be represented by tribes mentioned by Deborah then we’d be disappointed that the following three tribes didn’t get a mention:

- Judah

- Simeon

- Levi

Why didn’t Deborah mention Judah, Simeon, and Levi? Why weren’t they called? Why was there no expectation that they’d turn up?

- It can’t be because they were located far from the battleground – a quick glance at a map of the tribal allotments at the back of your bible will show that Reuben had further to come than Judah and Simeon and yet were called out for not answering the summons. Why not call out Judah and Simeon since they were closer?

- It can’t be because the event took place before the United Monarchy when the 12 tribes were one political entity (not least because the evidence for a united monarchy is pretty shaky). As we read in Judges 1:8 when Judah took the Benjamite city of Jerusalem (an event flatly contradicted by other events in Judges 19:10–12 and 1 Samuel), and as we read about the tribes that came up in response to the chopped up concubine of Judges 19:29–20:1, it’s clear that the scriptural narrative gives us a picture of cooperation across what later became the Judah/Israel border during the period of the Judges.

The answer is quite simple: as we saw in the previous post, the area of Judah, i.e. the hill country south of Jerusalem and the northern Negev, was practically empty in the 12th century BCE. The Song reflects the reality of the day – there wasn’t a Judah for Deborah to call on. Simeon, being landlocked within Judah, falls into the same category – they just didn’t exist.

So, what have we found? Let’s let Stager give his summary:

The Song of Deborah itself requires us to assume tribal and even supratribal orders that extended not only to the highlands but even to their kin in the valleys and plains. The most inclusive tribal grouping in premonarchic Israel was the confederation, a loosely structured alliance of tribes reinforced by religion and activated for mutual defense.35

So, in conclusion, it’s pretty safe to say the following:

- The majority of the tribes of Israel that we read about throughout the Hebrew Bible are mentioned in a song written down around 1100 BCE not long after the events it narrates.

- The song expresses an expectation that various people groups would turn up for battle when called, implying some sort of loose alliance between them.

- These people groups have names very similar to those of the later tribes of Israel.

- Where the song provides geographical information about the tribes it mentions, it matches the location given for those tribes in parts of the bible written much later.

Certainly, more could be extracted from the song, but for the purposes of this series, that’s more than enough to cast a lot of light on the period of the emergence of Israel in Canaan.

Oh, we forgot about Levi. We’ll deal with them in the next post.

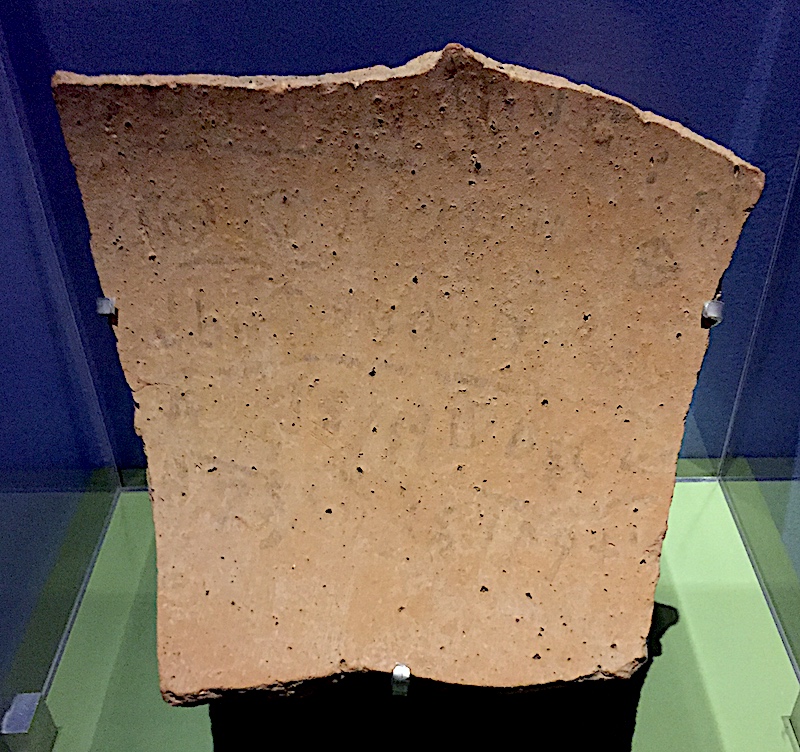

Featured image

A photo of Ta’anach I took on the outskirts of a tiny village called Ram On, a few minutes after someone shot out of a junction and crashed into my car. Thankfully neither my wife nor my kids nor the people in the other car were injured. That evening we checked into a hotel in Nazareth (not a mistake I’ll make again) and experienced an earthquake. Ba’al was not looking down favourably on me that day. So, please look at the photo for a full 5 minutes at least – I need to know the car crash was not in vain :)

Footnotes

-

Jens Bruun Kofoed, Text and History: Historiography and the Study of the Biblical Text (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2005), 43. ↩

-

Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible 10,000-586 B.C.E. (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 1990), 404–405. ↩

-

Gregory Mobley, The Empty Men: The Heroic Tradition of Ancient Israel (New York: Doubleday, 2005), 5–6. ↩

-

Elizabeth Bloch-Smith and Beth Alpert Nakhai, “A Landscape Comes to Life: The Iron Age I,” Near Eastern Archaeology 62, no. 1–4 (1999): 63. ↩

-

Albert E. Glock, “Taanach,” ed. Ephraim Stern, The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, Volume 4 (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1993), 1432. ↩

-

Abraham Malamat, History of Biblical Israel: Major Problems and Minor Issues (Brill, 2001), 107. ↩

-

Yigal Shiloh, “Megiddo,” ed. Ephraim Stern, The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the Holy Land, Volume 3 (Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1993), 1013-1016. ↩

-

George Foot Moore, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on Judges, International Critical Commentary (New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1910), 132–133. ↩

-

Robert G. Boling., “Judges, Book of,” ed. David Noel Freedman, The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 1109. ↩

-

Taken from Phillip Marshall, “Hebrew Language,” ed. John D. Barry et al., The Lexham Bible Dictionary (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016). ↩

-

Frank Moore Cross Jr and David Noel Freedman, Studies in Ancient Yahwistic Poetry (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.; Livonia, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.; Dove Booksellers, 1997), 18–21. ↩

-

William M. Schniedewind, A Social History of Hebrew – Its Origins through the Rabbinic Period (Yale University Press, 2013), 70-72. ↩

-

Also, if you want to read up on the minority view, rejected by the vast majority of the relevant scholars, that the Song of Deborah is a late, post-exilic work, see here. I must say, this layman is left rather unconvinced by the arguments. ↩

-

Waltke & O’Connor, An Introduction to Biblical Hebrew Syntax (Eisenbrauns, 1990), 4. ↩

-

Frank Moore Cross Jr and David Noel Freedman, Studies in Ancient Yahwistic Poetry (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.; Livonia, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.; Dove Booksellers, 1997), 3. ↩

-

Jacob Neusner, The Babylonian Talmud: A Translation and Commentary, vol. 15 (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2011), 55. ↩

-

Cheryl A. Brown, “Judges,” in Joshua, Judges, Ruth, ed. W. Ward Gasque, Robert L. Hubbard Jr., and Robert K. Johnston, Understanding the Bible Commentary Series (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 2012), 178. ↩

-

Robert G. Boling., “Judges, Book of,” ed. David Noel Freedman, The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary (New York: Doubleday, 1992), 1109. ↩

-

Norman K. Gottwald, The Tribes of Yahweh (New York: Orbis Books, 1979), 117-118. ↩

-

Jack M. Sasson, Judges 1–12: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, ed. John J. Collins, vol. 6D, Anchor Yale Bible (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2014), 282. ↩

-

Trent C. Butler, Judges, vol. 8, Word Biblical Commentary (Nashville; Dallas; Mexico City; Rio De Janeiro; Beijing: Thomas Nelson, 2009), 113. ↩

-

Robert G. Boling, Judges: Introduction, Translation, and Commentary, vol. 6A, Anchor Yale Bible (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2008), 101. ↩

-

The Holy Bible: English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2016) ↩

-

Jack M. Sasson, Judges 1–12: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, ed. John J. Collins, vol. 6D, Anchor Yale Bible (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2014), 276. ↩

-

Adele Berlin, Marc Zvi Brettler, and Michael Fishbane, eds., The Jewish Study Bible (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 519. ↩

-

Trent C. Butler, Judges, vol. 8, Word Biblical Commentary (Nashville; Dallas; Mexico City; Rio De Janeiro; Beijing: Thomas Nelson, 2009), 136. ↩

-

Robert Miller II, “When Pharaohs Ruled: On the Translation of Judges 5:2,” Journal of Theological Studies, Vol 59, no. 2 (October 2008): 654. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Amihai Mazar, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible 10,000-586 B.C.E. (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 1990), 290. ↩

-

https://www.baslibrary.org/biblical-archaeology-review/16/2/7 ↩

-

Lawrence E. Stager, “The Song of Deborah — Why Some Tribes Answered the Call and Others Did Not,” Biblical Archaeology Review 15, no. 1 (1989): 51–64. Available online (behind a paywall) here: https://www.baslibrary.org/biblical-archaeology-review/15/1/7 ↩

-

Jack M. Sasson, Judges 1–12: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, ed. John J. Collins, vol. 6D, Anchor Yale Bible (New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2014), 296. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

E.g. “Deborah’s song places Dan in its earliest coastal location” Trent C. Butler, Judges, vol. 8, Word Biblical Commentary (Nashville; Dallas; Mexico City; Rio De Janeiro; Beijing: Thomas Nelson, 2009), 149. ↩

-

Lawrence E. Stager, “The Song of Deborah — Why Some Tribes Answered the Call and Others Did Not,” Biblical Archaeology Review 15, no. 1 (1989): 51–64. ↩