Joshua 10 and 11: Genre and the focus on the leader

Over the course of the last few posts we’ve considered a number of aspects of Joshua 10 and 11 that mark them out as not being ordinary history writing. The final feature we’re going to look at is the chapters’ focus on Joshua, the divinely appointed leader of the conquest of Canaan.

One of the most striking features of ancient conquest accounts is just how focused they are on the accomplishments of the leader. Far from going into detail on the experience of their troops in battle, the heroics of individual soldiers, and accounts of difficulties experienced in the field due to loss of communication, etc, as we’d expect from modern war reporting, the purpose of ancient conquest accounts is to demonstrate the leader’s prowess in battle, to list off their achievements, and to claim divine favour.

Examples from Egypt and Assyria

The “narrow focus on a particular king and his accomplishments” in “annals, building accounts, and royal inscriptions of various sorts” was common across the ancient Near East1 – let’s take a look at a couple, starting with Egypt.

Miriam Lichtheim explains that,

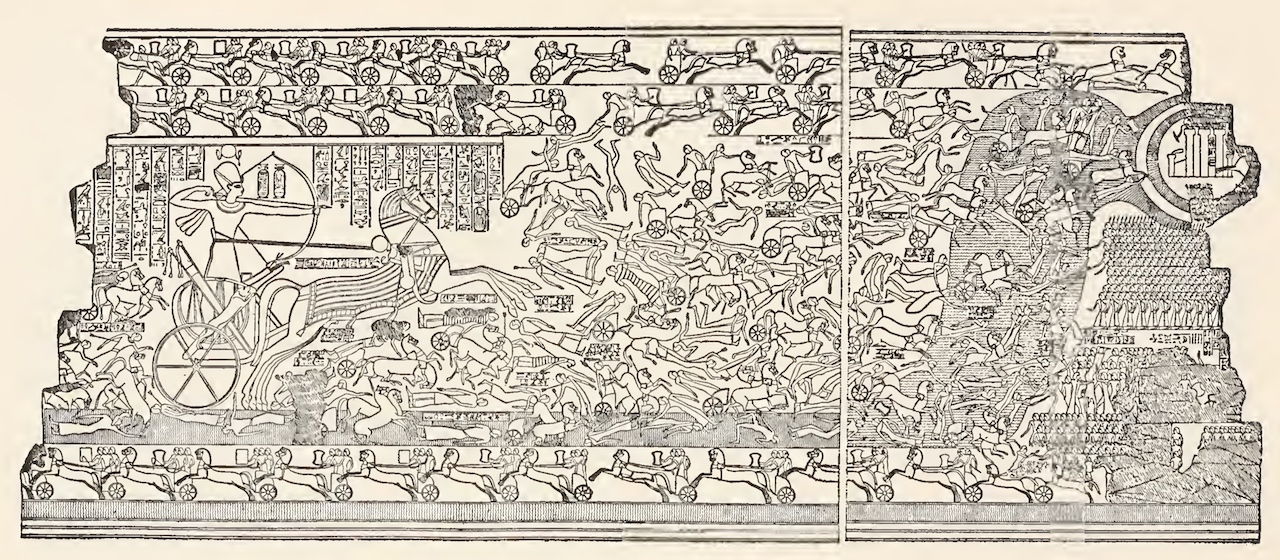

Since the beginning, Egyptian monumental art depicted a victory in battle by showing the king towering over all men and slaying the enemy. The New Kingdom enlarged the concept by adding the fighting armies and creating detailed battle scenes but always with the king in central position. These large-scale battle scenes, an innovation of Ramesside art, are the pictorial equivalent of the narrative battle poem, of which the Kadesh Battle Poem is the first known example, in that they both focus on the central heroic role of Pharaoh. This stylization necessarily distorts the facts, but the facts themselves are nevertheless presented in the details of the relief scenes, their captions, and the prose narratives.2

The image at the top of this post is an example of a relief of Rameses II depicted as the great hero of the battle of Kadesh. As Lichtheim also explains, we find the same feature in the conquest accounts that go along with the reliefs. In this instance the “bulletin” describing the same battle tells us the following about Rameses II’s actions:

His majesty slew the entire force of the Foe from Khatti, together with his great chiefs and all his brothers, as well as all the chiefs of all the countries that had come with him, their infantry and their chariotry falling on their faces one upon the other. His majesty slaughtered them in their places; they sprawled before his horses; and his majesty was alone, none other with him.3

Rameses II is described as killing all his enemies – he did so alone.

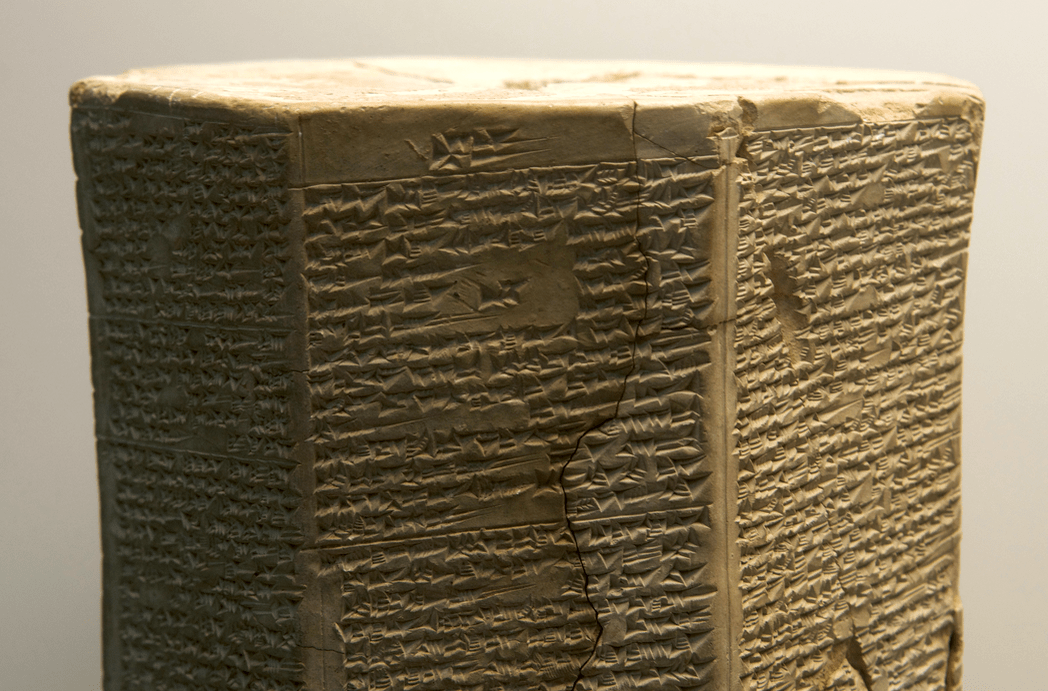

Another example, this time from the Annals of Tiglath-Pileser I that we’ve come across previously:

In the fury of my valor I marched against the land of Kutmuhi a second time. All their cities I conquered; their spoil, their goods, and their possessions I carried off; I burned their cities with fire, I destroyed, I devastated (them). The rest of their troops who took fright at my terrible weapons and were afraid of the mighty onslaught of my battle, sought the strong heights of the mountains, a difficult region, in order to save their lives. To the heights of the lofty hills and to the tops of the steep mountains, which it seemed impossible for a man to tread, I went up after them. War with skirmishes and pitched battles, they waged against me. I defeated them. The dead bodies of their warriors I cast down on the tops of the mountains like the Storm-(god), and I caused their blood to flow in the valleys and on the high places of the mountains. Their spoil, their goods, and their possessions I brought down from the strong heights of the mountain. The land of Kutmuhi in its entirety I brought under my sway, and I added it to the borders of my land. (Col. II, l. 89 — Col. III, l. 31)4

If taken at face value, just like the Egyptian bulletin we find the focus placed squarely on the leader and their achievements. We’re told almost nothing about the armies of Tiglath-Pileser I or those of Rameses II. But that’s because these aren’t modern war reports; they’re ancient texts with that aimed to serve very different purposes to what we’d expect war reports to look like.

With this background, let’s now turn to our chapters; Joshua 10 and 11.

The role of Joshua in the Southern and Northern campaigns

As we saw in the previous post about the common narrative structure of Joshua 10 and 11 both chapters open with an account of how the Israelites’ enemies instigated and organised themselves for battle. But, when the narrative’s attention moves away from the Canaanite or Amorite coalitions it doesn’t move on to the Israelites; instead it turns to Joshua. The chapters go on to tell us what Joshua did, sometimes mentioning that the Israelites helped out.

When we look at what’s actually happening in Joshua 10 and 11 we find that Joshua is either speaking, being spoken to by God, on the move, fighting, annihilating his enemies, hamstringing horses, burning cities, or killing kings. Only rarely are the Israelites mentioned as doing something without Joshua also being mentioned. Let’s take a look at a few examples of this heavy focus on Joshua.

We’ll begin at the end. How are the exploits of the Israelite army on the Southern Campaign described?

Jos 10:40–43 So Joshua defeated the whole land, the hill country and the Negeb and the lowland and the slopes, and all their kings; he left no one remaining, but utterly destroyed all that breathed, as the LORD God of Israel commanded. And Joshua defeated them from Kadesh-barnea to Gaza, and all the country of Goshen, as far as Gibeon. Joshua took all these kings and their land at one time, because the LORD God of Israel fought for Israel. Then Joshua returned, and all Israel with him, to the camp at Gilgal.5

Joshua did it all. Joshua defeated the land, Joshua defeated the kings, Joshua left none remaining, Joshua annihilated all who breathed, and on it goes. The summary of the Northern Campaign is no different:

Jos 11:16–18 So Joshua took all that land: the hill country and all the Negeb and [etc]… He took all their kings, struck them down, and put them to death. Joshua made war a long time with all those kings.

Again, it is Joshua who is portrayed as running the show.

The Israelites are mentioned a few verses later (“There was not a town that made peace with the Israelites… it was the LORD’s doing… so that they would come against Israel in battle, in order that they might be utterly destroyed…”) but Joshua soon comes to the fore again:

Jos 11:21 At that time Joshua came and wiped out the Anakim from the hill country, from Hebron, from Debir, from Anab, and from all the hill country of Judah, and from all the hill country of Israel; Joshua utterly destroyed them with their towns.

When it comes to the details of the towns that were taken, we find the same thing – usually the victories are attributed to Joshua with the Israelite army playing only an incidental role. Two examples from the southern campaign, Hebron and Debir, help to illustrate the point:

Jos 10:36–39 Then Joshua went up with all Israel from Eglon to Hebron; they assaulted it, and took it, and struck it with the edge of the sword, and its king and its towns, and every person in it; he left no one remaining, just as he had done to Eglon, and utterly destroyed it with every person in it. Then Joshua, with all Israel, turned back to Debir and assaulted it, and he took it with its king and all its towns; they struck them with the edge of the sword, and utterly destroyed every person in it; he left no one remaining; just as he had done to Hebron, and, as he had done to Libnah and its king, so he did to Debir and its king.

A close reading of the strange incident of the sun and moon standing still highlights the same point:

Jos 10:13–14 The sun stopped in midheaven, and did not hurry to set for about a whole day. There has been no day like it before or since, when the LORD heeded a human voice; for the LORD fought for Israel.

The writer explains that what was unique about the event was not that the sun or moon stopped, but that God listened to a man. But it was more than ‘listening’ or ‘heeding’.6 The same language is used in the context of the Israelites obeying God:

Ex 15:25–26 There the LORD made for them a statute and an ordinance and there he put them to the test. He said, “If you will listen carefully to the voice of the LORD your God, and do what is right in his sight, and give heed to his commandments and keep all his statutes, I will not bring upon you any of the diseases that I brought upon the Egyptians; for I am the LORD who heals you.”

These verses hold Joshua in a high regard – so high that it’s made out that God obeyed Joshua.

We could go on and on, but it’s left as an exercise for the reader to see just how many times the focus in these two chapters is placed on Joshua instead of the natural focus of a war report – the Israelite army.

The point of all of the above is to demonstrate just how Joshua-focused the two conquest accounts are, and that although this is not at all what we’d expect from a modern war report, it’s exactly what we’d expect from Ancient Conquest Accounts. Just like what we find in Rameses II’s and Tiglath-Pileser I’s conquest accounts.

Featured image

Figure 169 - Battle scene from the great Kadesh reliefs of Rameses II on the walls of the Ramesseum.7

Footnotes

-

John H. Walton, Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament: Introducing the Conceptual World of the Hebrew Bible (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2006), 219. ↩

-

Miriam Lichtheim, Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume II: The New Kingdom (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973–), 59. ↩

-

Ibid., 62. ↩

-

Daniel David Luckenbill, Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia (Illinois, University of Chicago Press, 1926), 77-78. ↩

-

Unless otherwise noted, all scripture is quoted from the New Revised Standard Version (Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1989) ↩

-

Thomas B. Dozeman, Joshua 1–12: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary (ed. John J. Collins; vol. 6B; Anchor Yale Bible; New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2015), 433. ↩

-

James Henry Breasted, A History of Egypt: from the earliest times to the Persian conquest (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1905), 452. ↩